Pallet shelter villages are transitional communities for people experiencing homelessness. They provide the dignity and security of lockable private cabins within a healing environment. Residents have access to a resource net of on-site social services, food, showers, laundry, and more which helps people transition to permanent housing.

There are more than 70 Pallet shelter villages across the country, including one near our headquarters in Everett, Washington, which opened one year ago. Everett Mayor Cassie Franklin was instrumental in bringing the site to life. Recently we held a webinar to discuss the affordable housing crisis, why unhoused people don’t accept traditional shelter, and the steps Everett took to build a Pallet shelter village. Mayor Franklin provided good insight into these issues. Before becoming an elected official, she was the CEO of Cocoon House, a nonprofit organization focused on the needs of at-risk young people.

Below is a lightly edited version of the conversation.

Pallet: How has the affordable housing crisis affected your area in the past three years?

Mayor Cassie Franklin: First of all, Everett has had a housing crisis. The West Coast has had a housing crisis for decades now, and the pandemic has only exacerbated that. So the last three years it has just gone out of control. Everett is about 20 miles north of Seattle. Seattle was always an affordable big city, and people would move to a more affordable working class community like Everett. Now Everett is also becoming unaffordable. I just actually had a conversation with one of our residents that her rent was going up $300 a month and she's on a fixed income. That is not going to be affordable, and that's going to lead folks like that individual into homelessness if we don't protect the affordability that we have in our communities.

Because affordable housing is for everybody. It is for our nurses, it is for our firefighters, our police officers, our baristas, our working families need affordable housing. Everett needs housing at all price points.

The homelessness crisis has escalated tenfold, I guess, in the same period. So I just want to say that they're both interrelated very important issues that we're working towards. And I see Pallet as a very important tool in addressing homelessness and making sure that we have pathways to affordability for folks.

Pallet: Can you discuss funding sources available to fund Pallet shelter villages or comparable models?

Mayor Franklin: Before actually all that federal funding that's available right now, we were interested in Pallet and interested in making it happen. So we started to work with the team to identify how we could do it using city-owned property. So that helps with the expense right there. If you take city owned property that's underutilized, that's just — you're holding it for future purpose.

We were also able to get a state grant from the Department of Commerce, our county human services, and of course, American Rescue Plan dollars. Pallet is so affordable. I think that as a city and you're trying to figure out your way out of this housing crisis or how to build a new shelter, you're talking millions of dollars, and it's overwhelming. It is so much more affordable that it's kind of mind blowing how much easier it is to get temporary shelter up. There are so many people that congregate shelter is not the appropriate solution for.

The folks that we were seeing in our city that were like, okay, we've got these great service providers, we've got these hotel vouchers, we've got these dollars in these programs, but none of our unsheltered population wanted to access those services. There were just too many barriers. And I needed a solution for the folks that were living in encampments, for the folks that really were service averse. We needed far less funding than we would have to buy a motel or build a shelter or acquire even a warehouse to house people.

The city continues to work on permanent supportive housing. That is our goal. We've built permanent supportive housing here. It takes years. We're very proud of it. We need so much more of it. We are continuing down that path, working with outstanding housing developers, our nonprofit partners that understand the population that needs services. But I can't wait four years for a new housing project to be built and for us to get all the complex funding for that. I needed something more quickly, and that's where Pallet came in to provide that bridge.

(Note: Federal funding from FEMA and HUD is also available to use towards building Pallet shelter villages, safe sleep sites, and other interim shelter solutions. Pallet’s Community Development team can connect cities and nonprofits with these sources.)

Pallet: What is the goal of these villages and what are the other measurable or quantifiable results that you consider successes?

Mayor Franklin: We had this area that was just a disaster. It was a huge encampment. We got so many complaints. It was not safe for the individuals out there. So we had angry residents complaining that we weren't taking care of the city. But I was also just really worried about the people that were living in those unhealthy conditions, health hazards. This is not an okay environment for people to sleep in.

We were able to get people inside living safely in their dignified four walls and the businesses that were impacted, again, this also helped us locate it. So all the NIMBYism like, ‘oh, this is going to make our neighborhood worse,’ actually it made the neighborhood better. It has improved the neighborhood. We took care of the health crisis. We have a safer neighborhood there now. And the people in the Pallet shelter community are after months, it takes time because these are service averse populations that have a lot of trauma from years of abuse on the streets and drugs and whatever illnesses they've been dealing with. But they are getting treatment, they are connected to social workers, they are getting medical treatment and some of them have been able to transition out of a Pallet [shelter] into permanent housing. So to me that's a huge win.

Pallet: How did you go about choosing the location you selected?

Mayor Franklin: It's the hardest thing right? No one wants to see people living outside. They get angry, but no one wants a shelter or any solution in their neighborhood, even affordable housing, which is just like housing. Honestly, people get worried about that. So the way we did it was I asked the team for a map of all of our public properties. I want every single public property. I want us to evaluate everything that we own, if any of those would be viable. I also asked to look at anything else if it was a site that they thought would be suitable. Probably not smack dab in the middle of a single family neighborhood. You're going to get the most NIMBYism and most pushback in that community. And so after the team, public works planning, our community development team and certainly working with Pallet, analyzed all of those different sites — how many people we would want to house and how we could get the services to the individuals — we identified one that was right behind our mission (Everett Gospel Mission). And again, that was hard because this was an area that was already being impacted by the services. We have the only shelter in the entire county right here in Everett.

And so they were like, ‘Are you kidding me? You're going to put more shelter in our neighborhood.’ The businesses and the residents in that neighborhood were scared, so that's why we looked at, okay, well, what can we do to improve the neighborhood? How can we make sure that this is actually going to be a positive impact, not a negative impact? And the no sit, no lie [ordinance] was very helpful.

We have two other Pallet shelter communities coming up. One is going to mainly house single adults, mainly single men. The next shelter is for women and children, and that is very close to a single family neighborhood. And so that is where that project will be going. And then a third site that we'll be discussing is on unused property that the city owns that is kind of somewhat close to residential, but more close to former industrial. So it's kind of like finding those transition properties in your city. That kind of where you're almost making everybody mad, your businesses and your residents, but it's not in the middle of anybody's area. Those borderline properties, and again, city owned.

Pallet: Anything else you’d like to add?

Mayor Franklin: I think separating the affordable housing crisis from the homelessness and kind of the street level issues that we're dealing with, they are not the same. The community gets them all mushed together, and that doesn't actually help us in our cause. So really talking about them strategically as separate issues that somehow they do relate, but they're separate issues. And so when you're talking about homelessness and the street level social issues and what we're dealing with there, finding solutions for non-congregate shelters are super important.

The main thing is land, education and balance. You've got to find the land and break through that, and that is achievable. Cities do have a lot of land. We did a ton of outreach before we put up the first Pallet shelter. Helping people understand this is not what you think it is. This is something very different. This is actually going to move people that are living outside causing problems for you inside and also educating the community. This is different than the other shelters you've experienced.

Breaking the cycle of homelessness in Aurora, CO

Pet ownership is a quintessential part of American life. Statistics show 70 percent of households across the country own at least one pet. From parks to specialty items, there's an entire industry catering to the needs of furry family members. But when a pet owner is unhoused, their ability to care for an animal is questioned.

A prevailing myth is that people without a stable place to live shouldn't own pets and should give them up. According to a Homeless Rights Advocacy Project (HRAP) policy brief, "this advice is predicated on the false belief that surrendering dogs to shelters is superior to having a dog live on the streets with its owner." But that's not true. The brief adds, "shelter conditions alone cause severe animal suffering and unnecessary death." Some also falsely believe people experiencing homelessness are unworthy of owning a pet and are incapable of caring for them. These misconceptions are dangerous and have led to the harassment of homeless people on the street.

Jennifer, Human Resources and Safety Specialist at Pallet, knows firsthand the value of having a pet while homeless. Jennifer's bond with her dog Bailey began when she was housed, but later they lived in a car, then an RV. Bailey helped fill the void in Jennifer's heart and alleviate the pain and suffering she was going through. Jennifer was dealing with personal setbacks and substance use disorder at the time.

"Even in some of my darkest moments, Bailey was the reason I didn't just give up and quit and die. Because then it was like, what's going to happen to Bailey?" she shared. "She was literally my reason for not giving up and helped me really get through a lot."

Jennifer took great care of Bailey and was attentive to her needs. Homeless pet owners often feed their animals before feeding themselves. For Jennifer, Bailey was a source of protection, companionship, and unconditional love.

"When you're in those situations of being homeless, you need something to hold on to, to keep going, to keep surviving. You can be a single mom living in your car, and CPS (Child Protective Services) will still leave you alone," Jennifer shared. "Just because you don't have a roof and four walls around you doesn't mean you're not functioning. It doesn't mean you're not living, and it doesn't mean that you're not doing the best that you can."

At Pallet, we understand the critical bond between pets and their owners. Because traditional congregate shelters don't allow pets, it's a barrier for unhoused pet owners to accept shelter. At Pallet shelter villages, unhoused people and their pets can stay together in a healing environment while stabilizing and preparing for the next step. Here's what a couple of pet owners staying in our shelters had to say about the benefits of having their four-legged family members with them.

"Most homeless people I've met in my time if they have an animal, they need it because it gives them clarity, some focus, and it gives them something to live for," John explained. His dog, Walter, brings him joy and is his best friend.

"They keep me grounded," Lynette added. "They're my life, really. They're my kids. They're very protective of me."

The numerous mental and physical health benefits of having pets don't suddenly disappear when someone is unhoused. Rather than calling into question their ability to take care of their beloved pet, donating food and supplies to the many local organizations, food banks, and veterinarians assisting them would be helpful. Better yet, support transitional housing communities that help people move from the street to permanent housing.

The unhoused community has as much right as those who are housed to build and maintain a bond with a pet if they choose to. The personal experience of Jennifer, John, Lynette, and countless others show having a pet in their life is invaluable.

This post is part of an ongoing series debunking homelessness myths.

Part One: They are not local

Part Two: Homelessness is a personal failure

Part Three: Homelessness is a choice

Part Four: Homeless people are lazy

Part Five: Homelessness can't be solved

Part Six: Homelessness is a blue state problem

*Name has been changed upon request for privacy.

Damone* is a lover of dogs – which is why he sought out Blue, a hyperactive cocker spaniel and husky mix. Blue is only a puppy, but she’s made a huge impact on Damone’s life.

Damone was born in Seattle, then moved to Mexico until he was seven or eight years old. He then came back to the United States, settling in Los Angeles where he’s been ever since.

A few years ago, Damone experienced a severely traumatic incident. Leaving him homeless, he spent over a year sleeping outside on the streets. He tried to go to mass shelters, but they were usually full, so he always had to find a new safe place to sleep.

Eventually Damone connected to mental health services, and was offered a spot to live in a Pallet shelter village. Blue came into the picture shortly after.

Blue, even in her energetic puppy phase, serves as a friend and confidant to Damone, who spends a lot of time on his own. When he needs calmness in his life, Blue has a way of sensing it and adapts to his mood.

“She keeps my mind occupied when I go through depression and anxiety phases. It’s almost like an aid,” he said.

Right now, Damone is working with the on-site service provider to find an apartment. He is looking forward to a more structured life: going to the gym, hanging out with friends, and doing things that make him feel good about himself again.

“I want to find my own peace and live in a normal environment again,” he said. “It’s a blessing to have a place to live [right now]. At the same time, I feel like I can overcome this and be part of society.”

Learn more about building the right shelter for people and their pets

If you’re looking for Pepe – a tiny tan chihuahua – you may miss him at first. His favorite place to hide is Juan’s zip-up jacket. Pepe’s tiny head occasionally pokes out, just far enough to get ear scratches and peek around.

Juan, Pepe’s owner, loves to keep him close for cuddling. The duo first met a few months ago, in a tough time in Juan’s life.

In 2021, Juan was riding his motorcycle and was struck by another vehicle. He woke up in the hospital with his arm bloodied and skin ripped off. His arm had to be partially amputated, and he was in the hospital for a month to recover. Since then, he’s gone through three surgeries, with more on the way.

The accident left him unable to work in his former job: construction and demolition.

As his arm healed and surgeries took place, Juan lived on-and-off with family members – like with his grandfather. But in December 2021, his grandfather passed away, leaving Juan alone without stable housing.

To cope with the loss, Juan’s mom gave him Pepe. She thought the little chihuahua would help keep his mind off what was going on at the time, and become a supportive friend. Juan temporarily moved in with his mom before realizing it “wasn’t going right.”

He ended up on the streets, without a job and income due to his injury. In February he tried out mass shelter, but found, “That experience wasn’t that good,” he said. He was surrounded by people in all different circumstances, and was worried someone might mess with Pepe.

In April, Juan moved into a Pallet shelter village in California. He has a shelter with a lockable door, air conditioning, a bed, and storage for him and Pepe. Juan knows it’s temporary, and looks forward to the future.

“Eventually I hope to get somewhere more stable,” he said. “If it wasn’t for [the motorcycle] accident, I wouldn’t even be here.”

Pepe gives him the support he needs to keep going.

“My life is kind of in shambles right now. [Pepe] gives me hope… I like seeing him when I wake up, when I get back to my room, I know there is someone waiting there for me. It’s not like I’m alone in the world,” Juan said. “I believe everybody should have a friend to guide them through life – that’s what Pepe does with me sometimes.”

Learn more about building the right shelter for people and their pets

My Lady – a black and white toy chihuahua – is often dressed to the nines. Her black shirt is stamped with a pink heart and perfectly paired with a matching tutu. Daisy, her best friend and owner, cradles her.

They have a mother-daughter relationship, Daisy describes it, which includes playing dress-up.

Knowing her love of chihuahuas, Daisy’s youngest daughter gave her My Lady as a gift. They’re inseparable, taking it day by day in one of Los Angeles’ Pallet shelter villages.

Before Daisy moved into a temporary Pallet shelter, she was evicted and living in her car. When the heater broke in December, it became unbearable.

While on the streets, she worried My Lady would be hurt or taken away. Staying near the train station, Daisy was approached by a police officer who told her, “I think at this point, you shouldn’t have a dog.” Daisy panicked.

“She’s more taken care of than anything, more than me. My Lady comes first,” she said.

The past three years have taken a toll. Daisy lost her housing, saw her sibling pass away from COVID-19, and constantly worries about her daughter, who is on the street with a substance use disorder. Daisy was formerly a registered nurse but had to quit because of her disability. She needed surgery on her back and her ankle.

Daisy eventually moved into a temporary shelter – without any pet restrictions.

My Lady has been there for support. “She fills all those pains,” Daisy said.

My Lady doesn’t just bring joy to Daisy. She’s got a personality to match her chic clothes. She’s a playful pup with furry and human friends. Instead of walking, she hops around like a rabbit, becoming a natural star of the show. She even has a well-known relationship with a German Shepherd.

Daisy and My Lady are always side by side, providing each other unconditional love, laughter, and protection.

Learn more about building the right shelter for people and their pets

California is home to Lynette. She grew up in the San Fernando Valley, eventually adopting BooBoo, a Pomeranian mix. BooBoo has been with Lynette for 13 years, with RaRa being born soon after.

A few years ago, Lynette and her pups lived in a house in Los Angeles. When a man forged quitclaim deed on her property, she lost her house.

Lynette moved onto the streets. She started off in a motorhome with her previous boyfriend, but she couldn’t handle the uncleanliness. Mostly, she despised the rats.

By moving into her truck, she controlled the space. But it wasn’t easy – especially during summer heat waves; the car became miserable and suffocating.

“I didn’t want to be out there, that’s for sure,” Lynette said.

BooBoo and RaRa became her protectors. Alert and ready to bark, they always knew when someone was unwanted near the truck. Nobody would try to open the doors. Lynette lived in her car for four years – losing track of time. She slept her days away, eating dinner late at night, missing sunrises and sunsets.

“It’s hard to get on your feet once you’ve dropped off,” she said. “We’re all lonely out there. It’s not an easy place to be. When you have pets, you’re not so alone anymore.”

The idea of living in a mass shelter never appealed to her. BooBoo and RaRa are too protective, and Lynette worried about strangers sleeping in nearby cots. Her truck had privacy: locking doors and guard dogs.

“I don’t think I’d ever go to those [mass] shelters,” she said.

Lynette eventually got into a Pallet shelter village with her own space to sleep, a locking door, and a secure area for the dogs to play. BooBoo and RaRa have their pick of dog beds – but they prefer cuddling close. RaRa sleeps curled next to Lynette's head, right on the pillow. During the day, the dogs go on long walks, and explore in the grass.

“[The shelter] has given me a really big stepping stone. I realize it’s nothing permanent, but it’s a stepping stone to get my housing and get me out of here,” she said. “It’s got me grounded again, where I can see the important things.”

After moving into a Pallet shelter village, Lynette began to plan: schedule surgery for her feet and neck, find a permanent place to call home, keep the dogs happy, and go back to school.

As she works toward her goals, she knows BooBoo and RaRa have played an enormous role in her life.

“If I didn’t have them, I don’t know what I would do. I probably wouldn’t be sitting here – I probably would’ve just ended it all if it wasn’t for my pets. I know I can’t because I have them. They’re my whole soul – my purpose – right now.”

Learn more about building the right shelter for people and their pets

In San Gabriel Valley, California, a group of unhoused people are on the path to permanent housing thanks to a Pallet shelter village. Esperanza Villa opened in late November 2021 with 25 Pallet shelters in Baldwin Park, CA. Each shelter has a bed, desk, shelving, climate control, electrical outlets to power devices, storage space for personal belongings, and a locking door. In addition to living in a dignified and private space, residents can access Pallet bathrooms and our laundry facilities.

The service provider at Esperanza Villa is Volunteers of America Los Angeles (VOALA), a nonprofit human services organization committed to serving people in need, strengthening families, and building communities. They provide meals, case management, and housing navigation. They also connect residents to mental and physical health services. Securing vital documents such as an identification card or birth certificate is a crucial step in the path to receiving housing. VOALA staff assists residents who need them.

VOALA Senior Program Manager Amanda Romero described the village as a safe place for our unhoused neighbors. They experience many emotions when moving in.

"It's definitely a sense of relief when they finally have a place where they're able to get services, and they're able to shower and do their laundry," she shared.

It's definitely a sense of relief when they finally have a place where they're able to get services, and they're able to shower and do their laundry.

– Amanda Romero, VOALA Senior Program Manager

Amanda describes the site as being quiet and mellow. Many people there are seniors, while some are working or going to school. Since opening, Amanda said six people have moved out of the village and into permanent housing. It was through a combination of housing vouchers (rental assistance) and family reunification. One woman who recently moved into her own place had been experiencing homelessness off and on for ten years. The successes at the site show when people have the opportunity to stabilize and access essential services, they can take the next step.

"About four more of the participants who are living there have emergency housing vouchers, so they should be housed soon," Amanda added. "It's just a matter of finding an apartment that accepts their housing voucher."

The surrounding community is also supportive of Esperanza Villa. Leading up to the site's opening, Baldwin Park Mayor Emmanuel J. Estrada held several information sessions to explain its purpose. The move helped dispel any misgivings people may have had and provided a greater understanding of the value of transitional housing.

Amanda said the village is an excellent alternative for people who — for several reasons — won't go to a traditional congregate shelter.

"We've gotten a variety of people from different walks of life, and we've really been able to help a lot of people," she shared. "The Pallet shelters are great because they can have their own space and sense of security and safety and a door that locks."

Homelessness Glossary: 15 terms to know

Recently Jerry and Sharon celebrated 26 years of marriage. This year they had more to commemorate than just lifelong companionship. At the same time last year, they lived outside and slept in a tent. The couple moved into Safe Stay Community, a Pallet shelter village in Vancouver, WA, when it opened in December 2021. The relocation was especially timely because of an unforgiving Pacific Northwest winter.

"It's great compared to a tent. Heat's good, especially in December when it's colder than heck. Or April when it snows," Sharon said. "And windstorms. We had a big windstorm that was taking tents down, but it never took ours down."

"It's a God send," Jerry added.

After getting settled, both underwent delayed surgery because they didn't have a stable place to recover. Now that they've moved into a Pallet shelter — a dignified space with beds, shelving, storage for their personal possessions, and a locking door — they've started the process of transitioning into their own place. Their son also lives in the community. He began taking online classes for a high school diploma.

"He's getting all A's. I'm so proud of him," Sharon shared.

There are 20 Pallet shelters at Safe Stay Community. The village replaced an encampment located in the same area. Outsiders Inn, an organization dedicated to lifting people out of homelessness through advocacy, support, and resources, is the service provider. All of their staff have lived experience.

Residents have access to a meeting space, bathrooms, hand washing stations, and a kitchen with a microwave, coffee maker, and air fryer. Meals are also delivered three times a day. A mobile health team visits the site frequently. The group includes a nurse, mental health professional, a substance use disorder clinician, and peer support. Pet care is provided through a partnership with the Humane Society. Case managers and housing navigators are also available.

In the months following the site's opening Jamie Spinelli, Vancouver's Homeless Response Coordinator, is proud of how well everyone is doing. Seven people have moved into permanent housing and a handful got jobs. Jamie has worked in outreach for more than a decade and has relationships with many residents.

She considers the greatest success of the site to be the positive shift in a resident who had been homeless for six years.

"He is the most stable I have ever seen. He was a very high crisis system utilizer. And he has not had to utilize any of those services since moving into this space," Jamie explained. "And that's only for a three-month period. But we would have had to utilize emergency services and crisis services for him probably no less than six times in that same time period when he was outside. "

He completed detox, is in recovery, and is now working at a local business near the site.

Jamie says the transitional housing village prepares people for the next step. A safe, supportive environment gets them back into a routine after living unsheltered. While residents work towards their goals, they bond and look out for one another.

Jamie eagerly tells the story of a successful paint night party in the community. One resident who loves the late Bob Ross made sure everyone tapped into their creativity.

"Everybody painted, and he would walk around. It was the sweetest thing I've ever seen in my whole life," she shared. "He walked around encouraging everybody because people were like, ‘I'm not a good painter.’ He said, 'Yours looks great. There's no mistakes. Only happy accidents. It looks beautiful.' Just encouraging everyone. It was probably the single greatest thing I've ever seen."

The site also gives the community a chance to engage with their unhoused neighbors. Many have come by to support residents, from making curtains for the shelters to offering employment. In April, Vancouver opened Hope Village, a second site with 20 Pallet shelters. Living Hope Church is the service provider. Jamie says it’s running smoothly and residents there are off to a great start. The city is also discussing the opening of a third site.

"I think one of the important things about these shelters, in particular, is that they offer an alternative to traditional shelter. Because there's a lot of folks who you could not pay to go into a traditional shelter," Jamie said. "I think these fill a gap that we've had for a very long time and are super needed."

UPDATE: In August the City of Vancouver released a six-month report on the Safe Stay Community. Highlights from the report:

● 14 people successfully transitioned to housing

● 40 people completed housing assessments

● 16 people obtained identification cards

● 11 people secured employment

● 1 person received a high school diploma

Read the full report.

Breaking the cycle of homelessness in Aurora, CO

Across the country, tens of thousands of youth don’t have a fixed place to call home. A 2020 count showed there were 34,210 unaccompanied youth experiencing homelessness. Ninety percent were between the ages of 18 to 24. It’s estimated 22 percent identify as LGBTQ+. According to the National Alliance to End Homelessness, youth homelessness is often rooted in family conflict. Other contributing factors include poverty, housing insecurity, and involvement in the juvenile justice system.

For two years, Sarah Allen worked as the Street Outreach Specialist at Cocoon House, an Everett, Washington-based nonprofit organization focused on the needs of at-risk young people (18 to 24-years-old). Their team provides short and long-term housing, outreach and prevention services.

Pallet talked with Sarah about her role as an advocate and former position. While there, she went into the community, especially skateparks, to provide unhoused youth food, supplies and talk with them about the services offered at Cocoon House. She was critical in ensuring that people across Snohomish County — a mix of urban and rural areas — were aware of the resources available to them. She shares what it was like to work with youth, lessons she’s learned, and common misconceptions about homelessness.

This interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

Pallet: How did you approach the youth you saw in the community? How did you build these relationships?

Sarah: Well, the first thing I do is make sure that I am not wearing really formal clothes. I'm not wearing dress shoes, I'm not wearing khakis. I'm not tucking in my shirt. Also in my appearance, I look younger. I was kind of younger, so I didn't seem much older to them. And in addition to that, I would go to skateparks and I would go to places where youth would be hanging out. There was consistency as well. For example, the Lake Stevens Skatepark, there's just a lot of teenagers that hang out there. I would go at the same time every Wednesday for a while, just connecting with people, handing out stuff to the point where the kids would feel comfortable approaching me.

There's a difference of need between someone who's 14 and someone who's 18. So I just made sure when I gave my little spiel or my elevator speech about it, it was applicable to them. And a lot of people might not understand what homelessness is.

Pallet: What did you consider a successful day?

Sarah: A successful day to me was really being able to connect with someone, a youth in particular, give them my card and then see them come into our drop-in center or our shelter or get sheltered. It always made me feel like I did my job right.

Pallet: The percentage of youth experiencing homelessness who are LGBTQ+ is high. Did you change your approach for those individuals?

Sarah: If I could tell, I would add that Cocoon House is an LGBT friendly place. We have people who identify that way as staff and then also just our culture in general, very respectful. For example, we had a youth in our parenting and pregnant shelter in Arlington, and they were a trans man, but they gave birth to their baby before they transitioned. And so I think about that particular person a lot and think, ‘Wow, that was really hard to do.’ And to be in a place that was safe enough for you to stay there for a long time, it really makes a difference versus other shelters that may not be as welcoming or be able to supply you safety for long periods of time.

I also wore a lot of rainbow pins on me and other kinds of signaling outfits as well. So that way it was more obvious to folks. I would let them make assumptions about me because they would be right. Because when you see someone who has a rainbow flag, you feel a little bit safer.

Pallet: Are there any lessons you learned while working in outreach?

Sarah: Yeah, I think actually I grew as a person and had a better understanding, in-depth understanding of community needs. Being able to see the range of different experiences because a lot of people just lump all homeless people into one box. That's not really fair because every single person is different. And it really helped me learn the difference between true compassion and pity, which is the antithesis of compassion. When I first started, I had pity. And I think a lot of people do not understand how limiting that is for folks. Like, ‘oh, I feel sorry for you.’ Compassion is saying, I see you and I hear you and you can do it. You're empowering them and you believe that they can do it.

I also learned a lot about street culture. There was a book [Street Culture 2.0: An Epistemology of Street-dependent Youth] that I read that was really impactful. The book would talk about how people perceive time when they're homeless, like all these other things that we don't see because we just judge people while we drive past them, while they have a sign up.

I think another lesson I learned is truly just listening and not assuming people's needs.

Pallet: What are some of the misconceptions people have about youth experiencing homelessness?

Sarah: One is drug use. ‘They use drugs, that's why they get kicked out and that's why they're using drugs on the street and that's why they're homeless.’ A lot of people have turned to drugs to survive being on the street. That's not the drugs causing them to live on the street. [They’ve said] ‘I'm on the street now and I have to stay up during the night time so the cops don't catch me or I don't get things stolen from me or I don't get hurt. So I have to take this substance to stay awake and I need to take this substance to go to sleep.’ I think that's something a lot of the regulars that I saw, they were using drugs because they just wanted to survive, which seems counterintuitive, but if that's what you got you're going to use it.

Another misconception is rebellion or youth are not listening and they deserve to be homeless. Some people think that, ‘oh if you just listen to so and so, if you just did this or that, then your life would be fine.’ People who are in the cycle of homelessness, I would say 90% have experienced some kind of physical, sexual, emotional abuse at some point, a lot of violence in life. Everyone just sees homelessness as the end result when there could have been a lot more steps preventing that person being on the street.

Also, I would argue that there's not a lot of things to do as a teenager and during Covid it was even worse. I feel like that also contributes to just lack of community and lack of belonging, lack of connection. At 18, everyone says, ‘oh, yeah, you're an adult now and just figure it out.’ I think that's really cruel to do to folks.

Another misconception is about using the fact that they have phones or maybe they might have a car or they might have things that might be considered luxury, but those things are necessary. Like, ‘oh, they should just sell their phone so they're not hungry.’ Everyone thinks that you should give up your items so easily. But how does someone get a job or contact people they need if they don't have a phone on them? Access a bank account, et cetera. I think everyone just wants them to look a certain way and be a certain way. And when people challenge that, they're very confused.

Pallet: What are some of the challenges the youth you worked with faced?

Sarah: The part about homelessness that people may not understand is that there's nothing that's your space and that you can claim for yourself. You're on someone else's couch, you're in someone else's car. It's very limited for you, especially if you've had a privileged life and then you don't. All of a sudden it's very shocking. You always feel like you’re in the way. It's very lonely, and you feel like everyone is kind of like communicating around you and not to you. And also there's just a lot, a huge amount of shame. I think that's the number one thing.

Pallet: What was your favorite part about working in outreach?

Sarah: I really enjoyed just interacting and talking to the youth that I was with and being able to just hang out with them, especially in the drop-in center that I worked in. I think that was my favorite part because I can actually hang out with them and talk to them for more than 30 seconds to a couple of minutes. I can see their personalities. I can see the difference in a good day and a bad day. I can learn what their favorite drink was or snack was. And maybe I was able to cheer them up by finding it for them, see them improve and reach their goals, be with them when times were hard.

I even got a Facebook message from one of the youth that I connected with recently. He said, ‘I really want to thank you for being there for me. Without you (and he named a couple other staff) I don't think I would be here.’ And now he's doing way better and living in Oregon and making improvements in life and moving forward, which I think is great. But I didn't do anything exceptional. I didn't give them a lot of cash. I didn't give them a miracle. I just showed up.

Pallet: What would you suggest someone do to specifically help young folks?

Sarah: I would definitely encourage folks to really reach out to organizations where they can spend time, face to face with youth by either mentoring, hanging out with them, maybe even sharing life skills with them for example. I know during Covid it's not always doable, but there's other programs like donating a meal, finding organizations that just lend a hand to folks. And really I would encourage people to step out of their comfort zone just a little bit more because I think a lot of people don't. They just drive past or walk as quickly as possible avoiding anyone who seems like they might need help instead of actually talking to them for a minute or maybe saying, I hope you have a good day or anything positive.

Pallet: As you were talking. I was thinking yeah, mentorship would be incredibly helpful.

Sarah: And I think it's really important that there's lots of representation of different communities as well, because as a cisgender woman who is White, I can only reach someone so far. There should be more volunteers and other mentors to reflect the community that they're in. More folks who can speak Spanish, more folks who can sign, more folks who are neurodivergent. Because there's a lot of need and a lot of different kinds of folks, and some people can just understand others better than others can.

Pallet: Is there anything else you'd like to add?

Sarah: I think there's one thing people can do. Be kind, listen and believe people when they tell you their story, even if it doesn't match your expectations.

Today Sarah works at Stanwood Camano Food Bank as a Program Coordinator. She’s assisting housed and unhoused youth and adults in this role.

How Pallet shelter villages have a positive impact on mental health

(UPDATED June 26, 2024)

Across the country, unhoused populations continue to grow. The leading causes of homelessness are economic hardship such as job loss, lack of affordable housing options, and mounting costs of living. Homelessness rates rise as rent prices increase: half of renters across the nation now spend at least 30% of their income on rent, while a quarter spend at least 50%. But even with economic conditions as a common factor, homelessness doesn’t affect all communities equally.

Some groups of people experience higher rates of housing instability. In particular, people who are LGBTQ+ are overrepresented among the unhoused population. Social stigma, discrimination, and family rejection put them at greater risk. According to a 2020 survey by UCLA's Williams Institute, 17% of lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults and 30% of transgender adults have experienced homelessness at some point in their lives, compared to 6% of the U.S. population. The Williams Institute is a research center on sexual orientation and gender identity law and public policy. Their research also shows:

- Nearly 30% of transgender respondents to the U.S. Transgender Survey who experienced homelessness reported being denied shelter due to their transgender status or gender expression. Approximately 44% reported mistreatment at a shelter, including harassment, assault, or requirements to dress or present as the wrong gender.

- 22% of LGBT adults live in poverty in the U.S. compared to 16% of non-LGBT people.

- 8% of transgender adults report experiencing homelessness in the past year, compared to 3% of non-transgender lesbian, gay, and bisexual people and 1% of cisgender, heterosexual adults.

New data also shows that nearly half (48.1%) of LGBTQ+ adults say they are financially unwell, compared to just over a quarter (25.7%) of the general public, and 30% of those who identify as LGBTQ+ reported experiencing discrimination while accessing financial services. These challenges put the LGBTQ+ community at a uniquely heightened risk of experiencing housing instability and homelessness.

LGBTQ+ youth and homelessness

In addition to LGBTQ+ adults, youth are also disproportionately affected. According to a 2022 report from the Trevor Project, 28% of LGBTQ+ youth reported experiencing homelessness or housing instability at some point in their lives—and those who did had two to four times the odds of reporting mental health challenges compared to those with stable housing. Additionally, research shows LGBTQ+ youth make up 22% of homeless youth. This means LGBTQ+ youth are 120% more likely to experience homelessness compared to non-LGBTQ+ youth.

A survey of 350 service providers across the country revealed the top four contributing factors for LGBTQ+ youth homelessness:

- Family rejection resulting from sexual orientation or gender identity

- Physical, emotional, or sexual abuse

- Aging out of the foster care system

- Financial and emotional neglect

In addition to homelessness, LGBTQ+ people are also at increased risk of experiencing poverty.

Because of stigma and discrimination, LGBTQ+ people are at greater risk of housing instability. In 2021, the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) announced the Fair Housing Act would also protect individuals from sexual orientation and gender identity discrimination. It’s a step in the right direction to expand federal protections for a vulnerable group. According to experts, improving school safety, workplace protections, and expanded housing options will benefit the LGBTQ+ community.

In Portland, Oregon, Queer Affinity Village is a welcoming atmosphere for LGBTQ+ self-identified neighbors. The village has 35 Pallet shelters, a dignified, private space with a locking door, bed, climate control, electrical outlets to power personal devices, and more. Residents have access to hygiene facilities, meals, and various social services delivered by an on-site service provider. Residents are working towards moving into permanent housing.

Homelessness is a complex issue without a one size fits all solution. Because of the unique obstacles LGBTQ+ youth and adults face, it’s imperative agencies and organizations tailor services to meet their needs.

Debunking Myths: Homelessness is a choice

Investment in human potential is a core component of our mission. People who live in Pallet shelter villages are a part of a community where they have access to a resource net of social services, which enables them to transition to permanent housing. We've created a purpose-driven environment where employees are supported and learning is encouraged.

As part of our commitment to creating sustainable jobs, we're proud to announce Living Wage for US (For US) certified Pallet as a Living Wage Employer. The nonprofit organization granted the status after analyzing Pallet's cash wages and benefits paid to employees. They specifically examined the lowest potential cash wages guaranteed to workers. Third-party validation is another step for us to show business can be a force for good.

A living wage is the minimum income necessary to afford a sufficient standard of living. When someone earns a living wage, they can cover basic necessities such as food, housing, and child services. Meeting this standard is one step toward reducing housing and food insecurity. According to For US, more than half of American workers don't earn enough to support themselves and their families at a basic level of decency from a human rights lens.

According to For US, these are the some of the benefits of paying a living wage:

- A household can afford heat without sacrifice

- Food insecurity decreases

- Fewer workers receive public assistance

- Workers can save for unexpected events

Methodology

When calculating whether a company can be certified as a living wage employer, For US analyzes the following county-based cost categories:

- Geography

- Family size

- Workers per family

- Food costs

- Housing costs

- Childcare costs

- Transportation costs

- Healthcare costs

- Miscellaneous (ratio of other expenses to food and housing)

- Resiliency (buffer for unexpected circumstances)

- Payroll taxes

The base wage at Pallet is $20.39. With benefits, the pay is calculated as $21.28. Washington state's minimum wage is $14.49. The living wage for Snohomish County is $21.02. We must submit pay and benefits information yearly and maintain compensation levels to keep the certification. Pallet employees receive annual reviews, and there are opportunities to receive merit increases throughout the year.

Why paying a living wage matters at Pallet

More than 80% of Pallet employees are formerly homeless, in recovery, or previously involved in the justice system. It's essential we pay everyone a livable wage and don't inflict further harm on a vulnerable group of people. Paying a livable wage positively impacts the employees and the greater community. In addition to a livable wage and benefits, Pallet employees also have access to life skills training and personal support services.

For US has also certified Olympia, Washington-based Olympia Coffee Roasting Co., Well-Paid Maids home cleaning company, and the Center for Progressive Reform.

Pallet achieves new status: Public Benefit Corporation

Pallet is on a mission to unlock possibilities by building shelter communities and employing a nontraditional workforce. Our villages for people experiencing homelessness provide the dignity and security of private units within a community. A resource net of on-site social services, as well as food, showers, laundry, and more, helps people transition to permanent housing.

Pallet began in 2016 as a Social Purpose Company (SPC), the Washington state equivalent of a B corporation. As of 2022, we’re proud to announce that we've transitioned to a Public Benefit Corporation (PBC). It means we use profitability to expand our impact. As our business grows, the more jobs and shelter villages we can create to end unsheltered homelessness. The change is a reflection of our growth as a company. PBCs are widely recognized across the country. More than 30 state legislators passed PBC statutes to make it easier for private businesses to establish themselves as a PBC or transition to one.

Think of a PBC as a hybrid of a nonprofit and for-profit organization. Our investment partners have allowed us to scale up quickly to meet the needs of the homelessness crisis. Those resources also allowed us to buy materials, secure a factory, and hire a skilled and consistent workforce. Because of our partnerships, Pallet isn't dependent on community donations and grants like a nonprofit. At Pallet, the mission is the driving force, not a substantial return on profits.

With this new status, we’ve joined other notable companies such as Kickstarter, a global crowdfunding platform focused on creativity, ice cream maker Ben and Jerry's, and clothing brand Patagonia who have all made similar commitments to purpose over profit.

Receiving Certification as a Living Wage Employer

In addition to transitioning into a PBC, Pallet has also received third-party certification as a Living Wage Employer. A living wage is the minimum income standard necessary to afford a sufficient standard of living. The designation from Living Wage for US recognizes our commitment to people. The organization analyzed Pallet's pay and benefits package. They use the Global Living Wage Coalition methodology, which considers several county-based cost categories before certifying a business. It includes geography, family size, workers per family, food, housing, childcare, transportation, healthcare, miscellaneous, resiliency, and payroll taxes.

The base wage at Pallet is $20.39. With benefits, the pay is calculated as $21.28. Washington state's minimum wage is $14.49. The living wage for Snohomish County, the location of our corporate headquarters, is $21.02. We must submit pay and benefits information yearly and maintain compensation levels to keep the certification.

Pallet employees receive annual reviews, and there are opportunities to receive merit increases throughout the year.

More than 80% of Pallet employees are formerly homeless, in recovery, or previously involved in the justice system. It's essential we pay everyone a livable wage and don't inflict further harm on a vulnerable group. People are our most important stakeholders.

Pallet proves business can be a force for good. Our values and the meaning of our name — lifting others up so they can be their best selves — is the company's north star.

How Jessie transformed his life and joined Pallet

Pallet shelter villages are dignified places for unhoused people to get themselves back on track. Each shelter has a locking door, bed, shelving, climate control, electrical outlets to power personal devices, and more. Residents have access to hygiene facilities, meals, and various social services delivered by an on-site service provider. These features are essential as people transitioning from living unsheltered are leaving challenging circumstances where daily survival — food and shelter — is the number one focus.

Sarah experienced homelessness before joining the Pallet team. She described winters and rain as the hardest.

"In the rain your whole tent gets soaked on the sides and on the bottom, and then you're left with puddles in there. And then getting kicked out of one camp because of the city," she explained. "You're so cold, and you're so wet. And then to be able to find dry clothes from whatever garbage can or from wherever you can find them."

With a singular focus on physical needs, there's little time and opportunity to focus on one's mental health while homeless. Traditional advice for how to tend to one's mental wellness includes: eating well, getting enough sleep, regular exercise, tracking gratitude with a journal, preparing lunches for the workweek, and seeking professional help. These tips have one thing in common: they can only be effectively carried out when housed.

Pallet shelter villages not only meet the physical needs of residents they also give them a chance to improve their mental health. The shift begins almost immediately, partly because they can get a full night of sleep. Rest is crucial because chronic sleep deprivation adversely affects health and quality of life. Residents don't have to worry about being woken up and told to move, or be concerned about safety since they can lock the shelter door.

"Their faces are one of the changes. From their countenance, going from a place of hopelessness to a place of life, a sense of belonging," shared Wanda Williams, Deputy Director of Residential Services at Urban Alchemy, the service provider at Westlake Village.

"Their faces are one of the changes. From their countenance, going from a place of hopelessness to a place of life, a sense of belonging."

– Wanda Williams, Urban Alchemy

"Even within a week, you'll see that they are sleeping better. You'll see that they're taking care of themselves and showering and things like that," Jamie Carmona told the Los Angeles Times in a feature on Chandler VIllage after it opened. "So even though they're not getting their [permanent] housing right away, you can see that it is helping them in many other ways."

Austin Foote is the manager of a Pallet shelter village in Aurora, CO. He's also worked in a congregate shelter. He described a significant difference in residents' well-being.

"In the congregate shelter, I would just see residents with just bloodshot eyes from just constant restlessness and just the inability to find any quiet or comfort," he explained. "There was no space to get away, to ever separate yourself and call something your own. It was constantly like a defense, defending your space."

Austin said because residents have their personal space, they can take time away from others when they need to. Their cabin is a place of solace to recharge.

"There's so much more follow-up because they've got that space to be able to go to. The dignifying aspect of it is a huge part of it. Safety is a huge part of it," Austin added. "We do our best to try to keep quiet hours, and we have staff do rounds to make sure that everyone's okay."

If a resident needs professional mental health assistance, services are available. While it varies from village to village, service providers have partnered with behavioral health providers who visit the site, or residents are provided transportation to an appointment. Because residents are at the same place every night, it's easier to connect them with the help they need.

Caring for one's mental health is a privilege housed people take for granted. Pallet's innovative model gives our unhoused neighbors the same opportunity.

Debunking Myths: Homelessness is a choice

Dignified personal space with a locking door, community, and access to services are critical components of Pallet shelter villages. For the last six months, unhoused people in Aurora, Colorado, have begun recovering from the trauma of living unsheltered. They're now healing in a village run by the Salvation Army Aurora Corps. The Safe Outdoor Space (SOS) has 30 Pallet shelters.

SOS manager Austin Foote described how new residents react when they move in, "There's kind of like this wonderment. ‘Is this real? Wait a minute. This is my space? I can come in, and I have food every day, and there's showers here?’" Austin is happy to confirm the village is, in fact, a safe and stable place where they can start the transition to permanent housing.

Austin considers himself an empathetic person and has a strong desire to help others. He thrives in his role at SOS, which allows him to build relationships with others and be of service. Before managing the site, he worked at a congregate shelter. He's seen firsthand the difference when people have a private space.

"Giving someone a safe place to stay and where they want to stay has increased our ability to do services. And to make changes in these people's lives on an immense level," he shared. "Our retention rates are way higher because it's comfortable. There's heating, there's cooling, they can design their place. They can lay it out the way they want. They can lock their door."

Along with Austin, there are two case managers at the site. He says because residents are staying in a set place — rather than moving around, which creates contact challenges — they can make individualized plans. In addition to having their basic needs met, staff assists residents with an array of social services, including securing documentation such as a birth certificate, housing navigation, and job assistance.

Those services offered by the Salvation Army have helped SOS resident Thomas regain stability. He told The Sentinel he's been able to get his driver's license and Social Security card. Now that he has an address, he also found employment. Thomas is grateful for the opportunity.

The village is a mini neighborhood, with residents hanging out with one another and playing board games with staff. When one person reaches a milestone like getting a job, it positively affects others. Austin says because they're able to see their neighbors' success for themselves, it encourages them to keep working towards their goals.

When SOS opened in July 2021, people initially stayed in tents. The following November, Pallet shelters replaced the tents. Here's a brief overview of the impact of the site from its opening through March 2022.

- 101 people sheltered

- 54% of residents obtained employment or employment services

- 11 people moved into permanent housing

- 7 family reunifications

- 72% of residents obtained benefits such as Colorado's Old Age Pension (OAP) program, Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI), and Supplemental Security Income (SSI)

- 91% of residents have obtained vital documentation such as an ID, Social Security card, or birth certificate

Because of the success of the first site, local officials opened a second Pallet shelter village last month, which the Salvation Army runs. Austin says other cities have reached out to them to learn how they're helping the unhoused community.

"I think the Salvation Army is changing the way in which homelessness is being looked at here in Denver," Austin shared. "I feel very blessed and proud to be part of a group of individuals in leadership that is really focused on trying to make direct assistance and change, as opposed to just kind of bandaging things."

What happens in a Pallet shelter village

Pallet manufactures rapidly deployable shelters for displaced populations. There are more than 70 Pallet shelter villages across the country for people experiencing unsheltered homelessness. Residents have a safe, private, and personal space with a locking door, plus meals, showers, and laundry. An on-site service provider also delivers an essential resource net of social services. This month marks six years since we started this journey to address a growing crisis.

Initially, the idea was spurred by Hurricane Katrina. Pallet co-founder and CEO Amy King and co-founder Brady King watched the devastation from the storm in shock. After seeing images of thousands of people in the Superdome — a football stadium turned emergency shelter — they thought the hurricane victims needed better options. Later, Brady brought up the idea again with disaster in mind. This time with more details.

"It was very specific. It needs to be lightweight, so you can airdrop it by military helicopter. It needs to be panelized, so it's easy to set up. It's got the foundation built-in, so you don't have to pour a foundation or excavate the site," Amy recalled. "I said, 'That's actually a really good idea. What you're talking about makes a lot of sense. We should build it.'"

Many of those initial elements are still present in the current design.

At this point, Amy and Brady had moved back to Seattle and started Square Peg Construction. They often talked about how expensive it is to build housing, how long it takes, and the growing number of unhoused people. Amy wondered if Brady's shelter idea would be helpful. After all, homelessness is a disaster, albeit a personal one not caused by Mother Nature.

They discussed the idea with employees of their construction company, many of whom had been homeless. The team thought it was a great idea, and identified its potential to help people who are living unsheltered. Their hard-earned insight helped us see the value in creating an alternative to the options unhoused people have to choose from.

Next, the two reached out to Zane Geel, Pallet's recently retired Director of Engineering. Zane took some time to figure out how to make it a reality. Rather than wood, the shelter panels would be made up of alternative construction materials. Pallet was born with an initial investment of $40,000 of personal funds. Zane built the prototype in his backyard. After design adjustments and hiring staff, the first Pallet shelter was ready. The team took it to an emergency response trade show in Tacoma, Washington, a city about 60 miles south of our headquarters.

"We were a little nervous about entering the marketplace with our product in homelessness. We thought disaster would be a better entry point," Amy explained.

They met Tacoma officials who were interested in the product because the city had just declared a homeless state of emergency. A few days later, they hosted an additional demonstration with city leaders. A week later, Tacoma placed an order for 40 Pallet shelters. They were ready to take an alternative approach to address unsheltered homelessness.

After receiving the call, Amy delivered the news to the team, "I walked in, and I saw Zane, and I just immediately started bawling. And I was like, 'We got it! We got our first sale. We sold 40 shelters to Tacoma.' And then he started to cry. And then everyone else in the room started to cry. And I was like, 'Oh, my God, we're going to do this thing.' It was so exciting."

Since setting up the village in Tacoma, Pallet has grown exponentially. We started with a handful of employees and there’s now more than 100. We've also improved the manufacturing production process. In the beginning, we produced three shelters each week; now, it's 50. There are Pallet shelter villages in 11 states, from Oregon to Arkansas. We've also partnered with mission-aligned investors who helped us scale and grow to meet the needs of the crisis. As a social purpose company, we use profitability to expand our impact. Amy is filled with gratitude.

Pallet began with the intention to help some of the most vulnerable members of our community, and that continues today. Our villages are not only bringing people inside, they are helping people regain stability to take the next step. We're also building a nontraditional workforce. More than 80 percent of Pallet's team members have experienced homelessness, substance use disorder, and/or the criminal justice system. We believe people's potential — not the past — defines their future. As we look forward to the coming months and years, we hope to expand our model.

"I would really like to see us further expand our workforce development model to encourage more companies to do what we're doing in terms of job offerings, with support for staff," Amy shared. “I never thought it would grow this fast, ever. I never imagined that this would be the reality, but I'm thrilled."

What’s in a name? How we chose Pallet

When Sarah sets her sights on a goal, she'll inevitably be successful. Being resourceful and determined has served her well. Sarah joined Pallet as a Manufacturing Specialist at the beginning of the year. Joining the team was a full-circle moment. She vividly remembers seeing our shelters in downtown Portland a couple of years ago. In a short time, Sarah has made an impact. Working in the factory was a bit of an adjustment at first, particularly standing on her feet for long hours. Still, she got used to it and quickly excelled at the various steps of building Pallet shelters.

"They were bouncing me around to all the stations, and the supervisors kept saying, 'normally people need to stay at a station for a certain amount of time before we move on, but you're learning really quickly,'" she shared. "It helped give me that motivation and confidence."

Within a few months, Sarah was promoted to Customer Service Coordinator, a new position on the Community Development team. She's the point person for customer concerns and coordinates assistance for prompt resolution. Sarah first heard about the job opening at a company-wide meeting. Pallet's Human Resources Director encouraged her to apply.

"I guess the fear of rejection played a major part of why I was hesitant," Sarah explained. She pushed through any doubts and decided the worst that could happen was she wouldn't get the job. But an upside would be others would know she's interested in a promotion. Since moving into the position, she's leveraged her connections already built with other teams to streamline the customer support process.

More than 80 percent of Pallet's team members have experienced homelessness, substance use disorder, and/or the criminal justice system. We believe people's potential — not the past — defines a person's future. Sarah and others have found stability through purposeful employment at Pallet.

Sarah earned a cosmetology license, certificates in early childhood education, and a degree in small business management entrepreneurship from a local college. She achieved these milestones after becoming a mother in her late teens.

"I worked also as a Montessori teacher, and I worked for Everett Public Schools, and I was a paraeducator. Then I taught middle school math," Sarah shared. She and her former partner also opened an afterschool education company where they served about 150 families. "We tutored low-income families through the no Child Left Behind Act. It was a neat experience, fun, and most of all rewarding. To know that I was part of a village in that child’s life will be everlasting on my heart.”

Sarah's warm smile and welcoming personality made it easy for her to connect with kids. She was doing well, but things took a turn after pain from an old injury came back. She went from taking medicine as prescribed to becoming addicted. She continued working and maintained a "normal" outward appearance. When she began using other substances, her life unraveled rapidly. She lived on the streets in her hometown of Everett, Washington, then later in Portland, Oregon.

"The winters and the rain were definitely the hardest, of course, because you're so cold and you're so wet. And then to be able to find dry clothes from whatever garbage can or from wherever you can find them," Sarah explained. "I've had to escape from fires from inside the tent because we'd fall asleep, and the candle would get too hot through the glass because it would be burnt out. Then that would heat whatever to catch on fire."

Sarah essentially disappeared for about two years while in Portland, but her mother tracked her down. When they reunited, Sarah reconnected with her family and three children. Shortly after returning to Washington, she entered treatment in January 2021. After treatment, she moved into a recovery house. She began an internship at Kindred Kitchen, a social enterprise creating stable futures by offering hands-on job training to formerly homeless and low-income individuals who need a fresh start. Sarah described the café as a supportive environment.

"I learned a lot. Even the most simple thing, like how to dice up an onion without the whole thing just falling apart everywhere," she shared. "It was a good transition from going crazy to not doing anything to then that to then this [Pallet]. It helped me really transition to the work mentality."

At the end of the internship, Sarah joined Pallet and now lives in her own place. A vital part of the culture at Pallet is embracing everyone no matter what path they've taken before arriving at the company. Sarah said she feels accepted and valued. It isn't necessary to hide her personal experiences. She’s thankful for the opportunity to rebuild her life and help others who are facing the same challenges she once did. Sarah is sharing her story to show that change is possible. She cautions others not to criticize our neighbors who are living unsheltered.

"You don't know everybody's path or journey, and you don't know how they got there. So try not to judge them and try to be part of the solution rather than just be somebody who looks down on them," she added. "There is hope for people to change. And people will change with the willingness and the support from the community and from others. They can do it, so just have faith that it can happen."

Debunking Myths: Homeless people are lazy

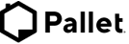

As part of our commitment to provide dignified space for people experiencing homelessness, we are continually improving our shelters. Conducting tests is one way to ensure Pallet shelter village residents are comfortable inside their cabins and safe from the elements. Recently two members of Pallet's engineering team — Jordan, Design Engineer, and Jessie, CAD Designer — oversaw an independent assessment of our heaters and the 64 sq. ft. and 100 sq. ft. shelters. Specifically, we wanted an additional analysis of thermal efficiency in cold weather and the power consumption of the heaters.

After researching testing facilities, Jessie found SGS, a world leader in product testing, inspection, and certification. Their facility includes state-of-the-art testing cells, on-site engineering personnel, and technical support staff. In addition to specific testing capabilities, we also needed certain physical requirements.

"We were looking for a chamber that would be big enough to hold four to five fully assembled shelters," Jessie shared.

Testing took place over four days at the SGS facility in Colorado. The shelters were placed inside a chamber that could reach -10 degrees Fahrenheit. It only took about 15 - 20 minutes to make temperature adjustments which allowed us to test a wide range of climates. The equipment SGS used included thermocouples that measured the temperature inside the shelters. A Hioki machine analyzed the power usage of the heaters.

"If we get a sense of how much a 4500-watt heater consumes in an hour at a certain temperature and we know how often a location is within that temperature range, we could say this is how many kilowatt-hours you'll consume in this amount of time," Jordan explained. "If we know how much power it's using in an hour, we can turn that into a dollar amount based on the cost of electricity."

These reliable test results enable us to paint a fuller picture of the electricity costs associated with a Pallet shelter village. We also evaluated the effectiveness of weather stripping and insulation of the sleeping cabins. Jessie and Jordan watched the data collection on monitors in real-time.

Overall, the testing was successful. The staff were meticulous in their approach and were helpful.

"Their techs, the senior research engineer, working with us, were super helpful, super accommodating with everything, even giving us that extra day when our truck was delayed," Jessie said.

Now that testing is complete, Pallet's engineering team is assessing the results to locate areas for design improvements and cost reductions.

"It will inform us quite a bit and give us an excellent baseline to investigate further design and improve our cold weather units," Jordan added.

What happens in a Pallet shelter village

Organizations, experts, and advocates within the homelessness field use specific words and phrases that aren't always common knowledge. To help bridge the information gap, below is a list of terms that will help you better understand issues related to homelessness. Terms defined include the types of homelessness, shelter and housing classifications, and tools used to address the crisis.

1. Unsheltered & Sheltered homelessness

Unsheltered homelessness refers to people sleeping outdoors in places not designed as a regular sleeping location, such as the street, a park, under an overpass, tent encampments, abandoned buildings, or vehicles. Sheltered homelessness includes people staying in emergency shelters, transitional housing programs, or safe-havens.

2. Congregate shelter

A congregate shelter is a shared living environment combining housing and services such as case management and employment services. Often in congregate shelters, people sleep in an open area with others. They are typically separated by gender and have set hours of operation.

3. Emergency shelter

A facility with the primary purpose of providing temporary shelter for homeless people. For example, cold and hot weather shelters that open during extreme temperatures are considered emergency shelters.

4. Imminent risk of homelessness

It applies to individuals and families on the brink of being unhoused. They have an annual income below 30 percent of the median income for the area. They don't have sufficient resources or support networks needed to obtain other permanent housing.

5. Chronic homelessness

People experiencing chronic homelessness are entrenched in the shelter system, which acts as long-term housing for this population rather than an emergency option. They are likely to be older, underemployed, and often have a disability.

6. Transitional homelessness

Transitional homelessness is when people enter the shelter system for only one stay – usually for a short time. They are likely to be younger and have become homeless because of a catastrophic event, such as job loss, divorce, or domestic abuse.

7. Episodic homelessness

Episodic homelessness refers to people who experience regular bouts of being unhoused. Unlike transitional homelessness, they are chronically unemployed and may experience medical, mental health, and substance use issues.

8. Hidden homelessness

Hidden homelessness refers to people who aren't part of official counts. They might be couch surfing at a friend's or a relative's house.

9. Transitional housing

Transitional housing provides people experiencing homelessness a place to stay combined with supportive services for up to 24 months. Pallet shelter villages are considered transitional housing. Residents, on average, stay three to six months before moving on to the next step, which includes permanent housing or reuniting with family.

10. Permanent Supportive Housing

This housing model provides housing assistance and supportive services on a long-term basis to people who formerly experienced homelessness. PSH is funded by the Department of Housing and Urban Development's (HUD) Continuum of Care program and requires that the client have a disability for eligibility.

11. Continuum of Care

The Continuum of Care (CoC) program promotes community-wide commitment to the goal of ending homelessness. The program provides funding for efforts by nonprofit providers and state and local governments to quickly rehouse homeless individuals and families. At the same time, minimizing the trauma and dislocation caused to homeless individuals, families, and communities by homelessness. For example, CoC program funds can be used for Rapid Rehousing, short-term rental assistance, and services to help individuals and families quickly exit homelessness

12. HMIS

The Homeless Management Information System (HMIS) collects and reports data on the characteristics of people experiencing homelessness and their service use patterns.

13. NIMBY & YIMBY

NIMBY = Not in my backyard. This label often refers to people who don't want the solution to a particular issue addressed in their "backyard." For example, they would object to a Permanent Supportive Housing building coming to their neighborhood or business. NIMBYism isn't limited to homelessness. It can apply to other issues. Conversely, YIMBY= Yes, in my backyard.

14. Criminalizing homelessness

Refers to policies, laws, and local ordinances that make it illegal, difficult, or impossible for unsheltered people to engage in the everyday activities that most people carry out daily. "No sit, no lie" laws, which prevent people from sitting or lying down in public, are considered criminalization of homelessness. Other examples include prohibiting camping in public, sleeping in parks, panhandling, and sweeping tent encampments (removing the personal belongings of people experiencing homelessness).

15. Point-in-Time count

This count is a one-night estimate of both sheltered and unsheltered homeless people nationwide. Local groups conduct one-night counts during the last week in January of each year. Because of the 2020 pandemic, some point-in-time counts have been suspended or occurred later in the year.

Hostile architecture and its impact on unhoused people