After spending much of his life in prison, Richard is now focused on helping others and continuing on the path of self-improvement.

Thumbing through a thick stack of certificates spanning from graphic design to dog training to a Lean Six Sigma Black Belt, it’s natural to be impressed by everything Richard has accomplished. What might not be obvious are the dark times he’s lived through, and that if it weren’t for some words of forgiveness and encouragement at a pivotal moment in his life, he may not be here today.

Richard’s childhood was tumultuous. Born in West Covina, CA, he spent his early years there before moving to Montana for a short stint with his mother and stepfather. It was there that Richard’s stepfather attempted to murder him.

“My stepdad was extremely abusive,” he recalls. “One day when I was seven, he tried to kill me. Left me for dead. My mom found me in the snow, bleeding.”

After being rescued, Richard was taken back to California and placed in a foster home. His mom was using substances at the time, and his siblings were all taken from her care. She regained custody when Richard was 14 and moved the family to northeast Washington state, but after getting in various fights and having general feelings of restlessness, he wanted to get away from it all. He made his way back to California on his own.

“I just got burned out, and I felt like I’d rather live on the streets,” he says. “I’d rather be away from everybody.”

From 14 to 18, Richard lived on the streets of Hollywood and on Venice Beach, intermittently visiting his mom in Washington for brief periods. During this time, he served time in juvenile hall and then Los Angeles County Jail for grand theft auto. He was on the wrong track with the wrong crowd, and he was aware of it. He left LA, thinking that being near his mom and brother in eastern Washington would improve his situation.

“You can leave wherever you want to leave, but if your personality stays the same, it's not going to change much, right?” he quips. “So I came up here, I started stealing cars, getting in trouble. I want to say normal kid stuff, but I know it's not normal kid stuff. But in the environment and the people I grew up around, that was kind of normal kid stuff.”

One night in July of 1999, Richard was hanging out at a park with a group of friends. Richard ended up agreeing to help steal a car with a few other people. It quickly became clear that the instigator in this escapade, a person several years older than his peers and someone Richard wasn’t well-acquainted with, had other plans.

He pulled out a gun and suddenly shot one of the other kids that came along. He then turned to Richard.

“He basically gave me a choice,” he says. “He had two guns on him, and he handed me one. I'm lost at this point. He says to me: ‘Hey, you're either involved or you're not. And you want to be involved.’”

Richard’s choice—to be involved—changed his life forever.

Wracked with guilt, Richard turned himself in. In Washington state, every suspect complicit in first-degree murder receives the same charges and penalties, regardless of if they’re considered the main perpetrator or an accomplice. He testified against the shooter while confessing to his involvement, accepting a minimum of 25 years in prison. Richard asked for 40.

“I was really messed up in my head,” he explains. “I guess I felt like, ‘Why didn't I stop it?’”

The victim’s family, present for the trial, heard Richard’s story. They saw his remorse and knew that it wasn’t his intention to harm anyone. Two of the victim’s uncles and his grandma even wrote letters requesting leniency for Richard, but it didn’t impact his sentence.

Several years after entering prison, Richard began to feel exhausted by the violence and chaos surrounding him. Whether he was involved in a fight or witnessing one, he became aware of how numb he felt.

He remembers the hopelessness he felt one particular instance after being released from solitary confinement: “I just broke down crying. Prison was breaking me. It was turning me into this animal, and I just didn't care anymore. It was ringing in my head: ‘I'm getting institutionalized. If I keep going on this route, I will spend the rest of my life in prison.’ There's no doubt.”

Richard said he saw three paths out of how he was feeling. The first: “I go down the route of being a monster, and I just become something I don't wanna be. Like something you see on TV, these guys in prison that spend their lives there.” The second was to find a way to go straight and become the person he was supposed to be. The final option was to take his own life.

Richard made the decision to take the third path. When the ER called his mom initially, they told her he had passed away, only to have to call back and inform her that he was still alive. He received a blood transfusion due to the large volume he had lost. For two weeks, Richard was confined to a bed and could barely move.

His recovery was slow. But a few weeks after coming to, Richard received something that would change his perspective and define his future: a letter from the victim’s grandmother.

He paraphrases its contents: “None of us want this. We want you to go on, we want you to live your life, we want you to live for him. I want you to promise me you'll never do that again. And in the process, I want you to promise me that you'll always try to help everybody else.”

This was when everything began to change. Richard vowed to cut ties with the violent groups he was involved with. At meals, he started to sit with people who were working on their degrees. He decided he wanted to make progress, too.

At that point, Richard had too many years remaining on his sentence to pursue his associate’s degree—prison policy operates on the assumption that if an inmate still has a long time to serve, they won’t retain the knowledge after being released. So, he began writing kites (internal requests to prison administration) to the Dean of Education.

They denied his request. Richard kept writing.

He started with one kite every six months, which they continually denied. Then he moved to sending them once a week for three more months, getting the same result. When he shifted to twice a week, the custody unit supervisor called Richard into their office, asking, “Are you ever going to stop writing these?” He assured them that he wouldn’t until they gave him a chance.

While they didn’t allow him to pursue his associate’s, Richard was permitted to take a graphic design course. Having a knack for painting and tattooing already, he obliged and obtained the degree after a year of coursework. Before he was even finished, he put another bug in the lieutenant’s ear about his associate’s degree.

Witnessing how serious Richard was about continuing his education, the request was run up to the superintendent, who eventually obliged on one condition: “You are the forefront. If you work out, we'll start giving it to other people with longer sentences. So you mess it up, you mess it up for them. You do well, then we'll consider them.”

To no great surprise, Richard completed the degree and only wanted to accomplish more. Unfortunately, the prison didn’t offer a bachelor’s program, which was his next goal.

“From that point on, I was just getting certificates in everything and anything you could think of,” he explains.

Instead, the administration recruited him to be a teaching assistant for inmates obtaining their GEDs. He then created a Release Readiness program for anyone wanting to prepare themselves for life after prison, regardless of sentence length—an unconventional idea, as most analogous programs are offered only to inmates with less than a year left to serve. After that, he was scouted to be part of the dog training program, becoming the de facto head puppy trainer after a couple years.

After several years of doing everything he could to help others and further his education, a friend told him to contact the attorneys at Seattle Clemency Project. He believed Richard would be a good candidate to apply for clemency, something he hadn’t even considered as an option.

“I'm literally sitting with people and helping them get their GEDs, helping them figure out college, helping people go to the law library, trying to help them get out and doing all that stuff,” he explains. “And I never even once thought about filing for clemency. It never crossed my mind, because at this point, I had a flat 25-year sentence.”

In their initial meeting, the attorneys quickly took a liking to Richard. Even though the chances of getting past the first phases of the clemency process are slim, let alone getting released after the hearing, they encouraged him to try. They told him it was going to be difficult, but they believed he had demonstrated that he was ready to be released from prison.

Richard spent the next year preparing for his clemency hearing, knowing that he had a chance if he could prove his honesty and humility. When the big day arrived and it came time to give his statement, which he had carefully prepared, he opted to set the paper down and just speak from the heart.

“I did this statement that was like 10 minutes long, and I didn’t read anything,” he remembers. “It just flowed.”

The result of the hearing was a unanimous decision to grant Richard clemency. The next step is securing the governor’s approval of the decision, which normally goes smoothly and without opposition. Which is why it was extremely unusual when Governor Inslee denied Richard’s case along with three other candidates that were also granted approval.

Richard was crestfallen but knew that he did all that he could and was still on the right track. For the next two years, he continued to hold his head high. He took art and music courses. He spent time talking to his then girlfriend on the phone, now his wife.

Then one day, out of the blue, he was told he had a call from the attorneys who worked on his clemency case. They informed Richard that Governor Inslee reversed his decision. What’s more, he overrode the typical step of scheduling another hearing to approve the release—an unprecedented decision.

Richard was dumbfounded: “I remember being like, ‘No way, this is not a real thing. This is a joke.’”

But on July 31st of 2021, as he walked out the prison doors to his girlfriend waiting for him and piled into the car with her son and her Chihuahua, reality set in.

Friends and family told him to take a few months to relax. But in true Richard fashion, he started a carpentry job the following week.

While searching job boards for better opportunities, he came across Pallet. He was intrigued when he learned about the emphasis on fair chance employment. As he worked his way up to higher earning positions in the construction industry and spent some time doing grassroots advocacy work, he waited for a position at Pallet to become available. When it did and he was offered a job, he readily accepted.

“I like what Pallet does,” he says. “They help everybody out. They don't care who they're helping, as long as they're helping somebody. That's kind of where I'm at in my life.”

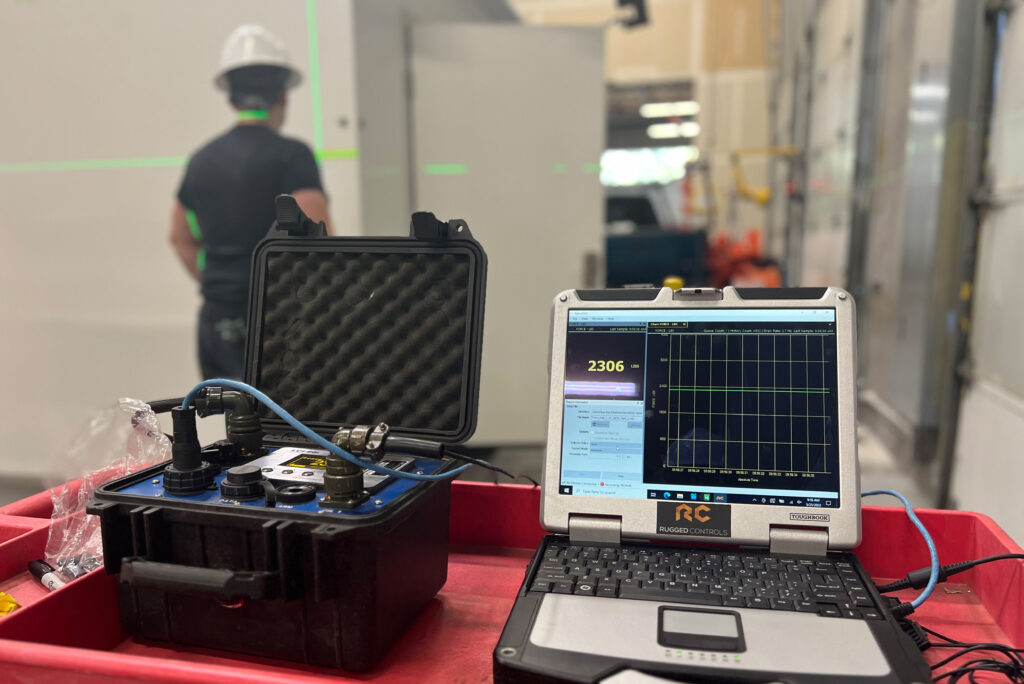

These days, Richard works on the Pallet team as an Engineering Technician. Having already earned his Lean Six Sigma Black Belt, he hopes to apply his knowledge and continue progressing in the field by earning his bachelor’s degree in either engineering or operations management.

With everything he’s endured and experienced in his life, Richard has learned a lot. He shares two of his guiding lights: first, do everything with a purpose; second, learn to accept change, even if it seems daunting.

“If something changes, I'm not so scared of it that I'm not willing to go through it. I just learn to flow and keep going, and I find another way. If it's progress, that's the good change. If my road washes out, I hike around it. If my base falls down, I build another one. It doesn't matter. If someone throws something in front of me, I just walk around it or step over it. So that's how it will always be. That's where I'm at.”

From launching a new product to expanding our footprint and creating our new workforce model, it was an eventful year at Pallet. Read on for our top stories of 2024.

As we look back on 2024, we are both proud of our advancements in providing safe, secure spaces for unsheltered populations and motivated to keep pushing forward. Even as we passed 5,000 shelters built in North America, expanded our reach into Canada, and released a new innovative product line to offer faster deployment and comfort for residents, the human displacement crisis persists—encouraging the Pallet team to continue working tirelessly until everyone has a stable place to call home.

Here's a round-up of our top stories from this year.

1. Pallet Hits the Road in California

Kicking off the year, the Pallet team embarked on a roadshow through California to showcase our new S2 product line and meet people working on the ground in their communities to solve their local displacement crises. We stopped in 11 different cities from Sacramento all the way to Los Angeles, displaying our S2 units and demonstrating the positive impact Pallet has made for unhoused communities across North America. [Keep Reading]

2. Launching Our S2 Shelter Line

Featuring an innovative panel connection system enabling even faster deployment, improved safety features, and increased comfort for residents, our S2 line is the next evolution of our in-house engineered and manufactured shelter products. Every decision we made in developing these new products was informed by input from residents living in Pallet shelters across the country and our own lived experience workforce. [Keep Reading]

3. Pallet's First Canadian Site Opens in Kelowna

Offering 60 individual shelter units for people experiencing homelessness in Kelowna, BC, STEP Place is Pallet’s first community installed in Canada. The City of Kelowna partnered with the Province of British Columbia and BC Housing to provide safe, secure spaces for people to stabilize and access onsite services provided by John Howard Society of Okanagan and Kootenay.

“We recognize the immediate need to bring unhoused people in Kelowna indoors and provide them the care they need,” said Ravi Kahlon, Minister of Housing. “Through this housing, people experiencing homelessness can be supported as they stabilize and move forward with their lives.” [Keep Reading]

4. Denver Opens First Village of S2 Shelters

Just in time for the New Year and part of Mayor Johnston’s plan to house 1,000 unhoused Denver residents by 2025, the opening of the city’s first micro-community also marked the first site comprising Pallet’s S2 Sleeper shelters.

“This is such a symbol of what we wanted to create,” said Cole Chandler, the mayor’s homeless czar. “It wasn't just about getting people indoors, but it's about bringing people back to life and helping people thrive. And you see that in this space.” [Keep Reading]

5. Introducing Our Purpose-Led Workforce Model

From the very beginning of Pallet, we have placed our team members at the core of our mission to give people a fair chance at employment. The majority of our staff have lived experience of homelessness, incarceration, recovery from substance use disorder, or involvement in the criminal legal system. With our Purpose-Led Workforce Model, we are taking the next step in helping our team grow and advance their careers. [Keep Reading]

6. Public-Private Collaboration in Santa Fe

Working together, the City of Santa Fe and Christ Lutheran Church opened the state’s first micro-community of its kind to provide shelter and supportive services for unhoused New Mexicans.

“It takes a community working together to really solve the challenge of homelessness, and that is our aim: to have zero homelessness in Santa Fe,” said Mayor Alan Webber. “We will keep working to make sure the people who are homeless in Santa Fe are housed, safe, secure, with respect, dignity, and with services.” [Keep Reading]

7. Tonya: "I feel like I'm doing something worthwhile"

Tonya knows Everett like the back of her hand. She spent most of her childhood on the north side of town but has lived in various neighborhoods throughout her life. So it seems fitting that now, after a decade of living on the streets of her hometown, she’s found a new path at Pallet and already moved into a place of her own mere steps away from HQ.

As one of the first participants in Pallet’s Career Launch PAD (Program for Apprenticeship Development), Tonya and her classmates are starting on the path to building independence and a brighter future for themselves. [Keep Reading]

8. Pallet Provides Shelter in Response to Hurricanes Helene and Milton

In rapid response to the disasters sustained in Florida following two major hurricanes, the Pallet deployment team jumped into action to build 50 shelters to help people get displaced by Helene and Milton get inside to safety.

By working closely with Pasco County administrators, county commissioners, facilities departments, and Catholic Charities, we were able to deploy and assemble the shelters mere days after the storms passed. [Keep Reading]

9. Connecting Pallet Team Members with Housing

At Pallet, our people are our purpose. Giving people a fair chance at stable employment and creating a supportive environment that fosters wellness and growth for all our team members is a crucial part of our mission.

A key part of this is ensuring that everyone on our team has all the tools and resources they need to succeed. In our work building shelter communities for displaced populations across North America, we know firsthand how having a safe, stable place to live is not only a basic human right—it is also the foundation for maintaining health, helping those with substance use disorder on their recovery journeys, and healing trauma.

That’s why we are proud to have become a Community Partner with Housing Connector, an organization that helps find housing for marginalized individuals and families. In our first year of the partnership, Housing Connector has been instrumental in finding housing for 4 Pallet team members by removing barriers and locating available properties. [Keep Reading]

In her short time at Pallet, Tonya has embarked on her recovery journey, found housing after experiencing homelessness, and set her sights on a skilled future career.

Tonya knows Everett like the back of her hand. She spent most of her childhood on the north side of town but has lived in various neighborhoods throughout her life. So it seems fitting that now, after a decade of living on the streets of her hometown, she’s found a new path at Pallet and already moved into a place of her own mere steps away from HQ.

Although she was born the middle child of five siblings, Tonya grew up as the eldest in the house, as her two older sisters lived elsewhere with other relatives. She was a natural athlete, playing basketball, volleyball, and running track for her high school teams.

Her stepdad was not only a solid supporter of Tonya and her siblings, but also played the role of coach in her athletic training. But even with bright prospects to play on a college level, Tonya felt as though something fundamental was missing due to her unconventional family dynamic.

“In high school I had a lot of scholarships to play different sports for different colleges, but my family was really broken, and I was looking to fill some kind of void,” she explains.

Tonya had her first son at age 15, which contributed to the loss of all her scholarships. Despite this massive shift in planning her future alongside the new responsibilities of becoming a mother, she worked tirelessly to graduate high school on time.

This feeling of accomplishment was short-lived. Out of school, Tonya got a full-time serving job out of necessity, which allowed her to secure her own apartment. Then she began using substances.

Life quickly began to spiral: she lost her job and was evicted after taking out short-term loans and falling behind on payments. Feeling lost and insecure about her ability to care for her child in such a tumultuous state, Tonya called her oldest sister, who promptly came to pick up her son and raise him in eastern Washington.

The lack of structure and trauma of living unsheltered caused Tonya to enter survival mode. She lived day-to-day, often couch hopping to friends’ houses or scraping together enough money for a motel room for the night.

“I was just really trying to figure out how, and where, I was going to sleep,” she says. “It was really hard being a young female, homeless out on the streets.”

In the final several years of being unhoused, Tonya lived with her boyfriend in a tent. She says they often wouldn’t be able to get into nightly shelters due to a lack of beds, and they weren’t interested in being separated.

During this time, they routinely talked about their hopes of getting clean. One day, he returned from the library to announce he’d arranged appointments to apply for a recovery program. From then on, they fully committed to sobriety and moved into separate sober living houses. Tonya immediately knew she made the right decision upon moving in.

“Oh my gosh, it saved my life,” she beams. “The structure has been great for my first year of sobriety. I really have been able to actually work on my consistency with my kids, with showing up for myself. I have so much support at that house. It’s been great, I love it.”

It was there that Sarah, her house manager, told Tonya about Pallet.

“She was telling me about this opportunity for people like us, who have a record, who don't have a lot of job experience, who have been homeless,” she recalls. “And I just thought it was a great opportunity to broaden my horizons when it comes to working and figuring my life out. So I suited up, I showed up, I tried it out, and now here I am.”

Tonya says she finds fulfillment working on the production floor and joining the deployment team to assemble shelters at new Pallet village sites.

“I feel accomplished,” she explains. “I feel like I'm actually doing something worthwhile, like I’m actually doing something good and not just wasting space. I've always felt like I've just been wasting space for a long time.”

In the short time participating in Pallet’s Career Launch PAD, Tonya has accomplished tremendous growth and plans to use her new skills to pursue a career as an HVAC technician. She says she’s not only enjoyed the hands-on lab sessions in the pre-apprenticeship program, but also taken a liking to the applied mathematics required for this skilled trade.

Outside of work, Tonya’s also made great strides with her family. She has moved into her own apartment with her boyfriend along with her two youngest kids. She’s close with her mom, who is now six years clean. Her own recovery is strong.

Given the progress she’s already made, we’re eager to see what great things await Tonya with her next steps.

Tonya's Progress Update: January 2025

Sometimes progress is small steps, other times it’s great strides.

Since starting Pallet’s Career Launch PAD four months ago, it’s decidedly been the latter for Tonya.

“I moved into my apartment and I’ll have a year clean next month, and I got my oldest son back in my life,” she says. “I got a gym membership—I vowed to never touch the basketball again when I started using drugs, but now that I’m clean I’m getting back into it. I’m gonna go get my license next week. Everything seems like it’s going smooth.”

Starting out, Tonya had her reservations about starting the program and getting back into a classroom setting. But once she gained some momentum, her concerns faded away.

“I was nervous in the beginning because it's been a long time since I've had to do any kind of schoolwork and be consistent with anything in my life,” she reflects. “So I was definitely nervous, but as I got the hang of it, it's definitely gotten me excited and it’s been smooth sailing since then. So I'm not even nervous about it anymore.”

One thing that surprised Tonya was how much she enjoyed the math components in the CITC program. She never thought she liked the subject in high school, but that changed when it was applied in the context of knowledge she would need in her future HVAC career.

“Back in school, I told myself: ‘I’m not good at it, I hate it, I can’t do this,’” she explains. “I’m coming into it this time as an adult with experience. In the beginning I was surprised that once they touched base on the course work, I felt like, ‘Oh yeah, I kind of like this.’ And then I got the hang of it.”

After getting her first grades in the mail and completing certifications in safety, CPR, and tool operation like the forklift and jackhammer, Tonya’s confidence his risen and showed her how capable she is.

“We got our first grades in the mail, and when I saw how good I was doing, I was like, ‘Wow,’” she says. “Like, ‘Wow, I’m really doing this.’ And it’s a really good feeling of accomplishment that you’re actually doing stuff for yourself. That made it feel real.”

Week to week, the schedule of attending classes at CITC and working at Pallet the rest of the week is working well for Tonya by setting up structure and expectations for herself.

“It helped me with routine and discipline,” she says. “I know what I need to do, I know how to prepare for the week: for school, for work. It’s a good transition, a different way to live. This time last year, I had no kind of schedule. Nothing. So it’s very refreshing.”

Adjusting to this new way of life didn’t come without some challenges. Tonya says it’s been difficult keeping up with certain financial obligations, but she’s not giving up.

“In the beginning it was child support and then I got past it, and now I'm back in the same spot again,” she explains. “But it's just a matter of putting some work in to figure it out. So I'll get through it again. This is the kind of stuff that makes people want to quit their jobs to start selling drugs again: ‘I can't get ahead.’ But I've been working too hard. I have too much support. Why go backwards? There's always a way to get through it, you know?”

Having clear goals set for her future and seeing the progress she’s already made is what keeps Tonya going. She says showing up for herself and making good decisions for her kids is one of the best feelings she could have.

“I'm proud of suiting up and showing up,” she says. “I'm proud of myself for continuing to do something with myself on a consistent level. I like the fact that I’m setting an example for my kids—it feels good that people actually look up to me and come to me for advice or trust me with certain responsibilities and know that I’m actually going to be there. It’s a really good feeling.”

Tonya's Progress Update: March 2025

Life is often a balancing act. Between adjusting to her schedule at Pallet, participating in courses at CITC, having her kids back in her life, maintaining her own apartment, achieving a year clean, and even helping her mom after an electrical fire damaged her house, Tonya says “crazy busy” would be an accurate description of how things have felt lately.

Even so, she’s keeping her head up and taking everything in stride.

“I’m just trying to get back into the hang of being a mom,” she says. “But some things are natural. I’m just really trying to figure it all out.”

She says moving into her own apartment is a big step up and feels like the start of a new chapter.

“The fact that I have my own place is beautiful,” she shares. “I have my family, my man, and we’re starting to live our life correctly.”

Based on what she’s learned about finding a job post-graduation, Tonya says while HVAC is still on her radar as a career path, she’s open to other options. Her main concentration is finding a job after graduating the program that allows her to have a stable income, gain some work experience, and explore her interests.

“I shifted [my focus],” she explains. “I’m definitely still intrigued and interested. But in the meantime, to pay the bills I can just tap into something else and see if I like it. Because I don’t know if I’ll like it until I do it, you know?”

Along with her fellow Launch PAD participants, Tonya is currently taking classes focused on electrical, which will be followed by a section on plumbing. But she said learning carpentry skills during their class project building a doghouse was a recent highlight of the program—even if the process didn’t click until actually putting the hammer to the nail.

“I’m a hands-on learner: you can’t show me a picture or read a couple sentences about something and expect me to know what it is,” she says. “I’ve never dealt with carpentry, I’ve never dealt with tools until I worked here. So for us to go and make the doghouse and apply what we learned, that was me learning it. But in the end, the whole thing was fun.”

Tonya says that while she is eager to know what life will look like after graduation, she’s confident in her new skills and happy to pass on the same chance she had to incoming members of the program.

“I have gotten used to working here, I’ve got my routine down,” she says. “But at the same time, I’m excited to branch out and to give other people an opportunity to do what I did. I know so many people that could get started if they could just have a job like this.”

Ultimately, Tonya knows that her experience working at Pallet and taking courses at CITC will set her up to pursue her dream of going to college and attaining a career in social work, where she’ll have the chance to fulfill her passion of helping others.

Given how hard she’s worked to get where she is today, we know she has the drive and talent to make this dream a reality.

Meet the other three featured participants in Pallet’s Career Launch PAD and read their stories.

Overcoming years of substance use and incarceration, Jeff is using his time at Pallet to forge a path to self-reliance and strong family relationships.

Family is everything to Jeff. Through incarceration, addiction, and every dark moment he’s faced, his relationships are what kept him grounded and moving forward. Now nearly three years clean and working toward running his own business full-time, he says it’s made all the difference.

“For me to be sitting here right now is nothing short of a miracle,” he explains. “My family and my higher power are what made that possible.”

Jeff spent his childhood living with his father and sister in Alaska’s Matanuska-Susitna Valley just north of Anchorage. He was taught from an early age the virtue of earning your keep by hauling and packing wood to fuel their barrel stove among various other household tasks.

“Growing up was awesome,” he recalls. “Hard work, you know, which is what’s translated into who I am today. So I grew up always having lots of chores and got a good work ethic ingrained from day one.”

In school, Jeff played football and was on the boxing team. But he had plenty going on outside of class: he started drinking and smoking cannabis around age 13; he got into motorcycles, learning to ride and maintain his first bike; he routinely hitched rides down to Anchorage with his best friend to work odd jobs at the truck and trailer dealership where his friend’s dad worked as a mechanic.

“We would go and we'd work around the shop there or his buddy would pay us to come work,” he recollects. “We’d be sandblasting painting equipment, doing different lightweight mechanics stuff, heavy equipment, working on bikes and cars or trucks. Whatever work we could do.”

Up until high school, Jeff says life was simple.

“That was pretty much my childhood: work, go to school, hunt, fish and drink.”

In 11th grade, things started to change for Jeff. He began failing some of his classes, which meant he was barred from playing football in his senior year. Not long after, he got into an altercation with one of his teachers and was promptly expelled from school.

“I started doing cocaine around the time I started driving and then things kind of spiraled a little bit out around that,” he says. “It's no longer just working or whatever—then all the other bull**** comes in.”

For the next year Jeff and his friends lived on a remote property in the woods, using drugs and growing marijuana. One day, his dad and uncle showed up to put an end to it: they told Jeff he’d be moving down to Oregon to live with his uncle and get his act together.

Once in Klamath Falls, one of the main house rules was prohibiting Jeff from talking to or seeing his mother, fearing that her substance use would be a bad influence. But when his uncle was gone working in the oil fields of Alaska, Jeff took the chance to call his mom and go over to her house.

The night that Jeff reunited with his mom was also the night he met his future wife and fell into the world of methamphetamines. The next period of his life was defined by this relationship and the circumstances surrounding their lifestyle of selling and using drugs.

The sister of one of Jeff’s mom’s friends, they hit it off immediately. Things moved fast after that: Jeff began living with her and her young son a few months later and they became their own family unit. But not even a full year after they met, Jeff got into legal trouble and her son was taken by child protective services as a result.

This prompted his first stint at recovery. Both of them entered programs and got clean, allowing them to take back custody of her son. What followed was several years of calm and stability: they got married, moved in together, and had a daughter of their own. One year on Christmas, Jeff met up with his friend, who offered him drugs.

“I don’t know why I did it, but I did it,” he says. “I just quickly went downhill. And within nine months I was in jail for the first long sentence, and it was five years.”

This chance encounter and Jeff’s relapse set off a chain of events entailing multiple incarcerations and participation in different recovery programs. While approaching the release date of his last sentence, a couple promising opportunities arose for Jeff, and he was determined to make a path out of the life he’d grown to know.

Upon being released in Seattle he was able to move up to Everett and rent a room from his sister and brother-in-law, who quickly connected Jeff to his best friend Josh. Josh told Jeff about Pallet, and the company’s focus on providing fair chances to people who have experienced incarceration and substance use disorder. Jeff had a feeling this was the direction he needed and applied right away.

“I liked the idea of how they were willing to give people opportunity, a chance, and the idea of getting further in my education was something I wanted and needed,” he says. “And to get that in addition to surrounding yourself with like-minded people that are facing the same struggles—I thought that was pretty amazing. So I just set my mind on waiting and prayed about it, and here I am.”

Since starting at Pallet, Jeff’s focus and determination have led to great progress in his future career and personal life. This December will mark three years clean. He saved up enough to buy a new truck, which he uses for independent contracting jobs after his shifts on the manufacturing floor. He’s joined the deployment team, seeing firsthand the positive impact Pallet’s shelter communities have for people who have been displaced. He's reconnected with his daughter, and is currently planning on a trip down to Oregon to see her and meet his grandchild for the first time.

For now, Jeff is dead set on working hard and planning for the future. He says the steadiness of his life and the support and encouragement from his coworkers are making it easier.

“Everybody here is willing to make themselves vulnerable to help you succeed,” he says. “There's no other place in the world where you’ve got coworkers like that.”

After completing Pallet’s Career Launch PAD, Jeff is determined to leverage the technical skills he’s learned and the certifications he’s obtained to operate his own business and maintain his relationships with his family. For good reason, he’s betting on himself.

“My vision is that when we graduate that class, I can move on to just work in my own company completely and move forward,” he says. “Because when you work for yourself, you get what you're worth.”

Jeff's Progress Update: March 2025

To say Jeff has been “busy” since starting at Pallet would be a massive understatement: between work, courses at CITC, and operating his own commercial maintenance business, days off are few and far between.

“My business is thriving,” he says. “It doubles every quarter, which is definitely a plus.”

With graduation from Pallet’s Career Launch PAD nearing, Jeff has his sights set on the future. He says right now, he’s focused on two possible paths: retrofitting LED lighting in commercial buildings to meet compliance for upcoming Washington State building codes, or hydro jetting drains. His research of the current job market led him to these occupations, but he also is confident he can continue in his current line of work.

“There’s a lot of work [in these fields] and it’s very good money,” he explains. “But I can always fall back to windows or pressure washing or any maintenance really, because I can do it all.”

Jeff has also established stability and independence outside work. He’s currently living in a house with a fellow Pallet coworker, but as their lease is up in a few months, he’s already searching for a new spot—ideally one with a garage where he can store his truck, dirt bike, and other prized gear.

This extra space could come in handy, as Jeff is planning to buy a new bike with the earnings from his business. He hopes to ride it when he competes in the Desert 100 dirt bike race next month in eastern Washington, an event he’s never experienced and something he’s very much looking forward to.

But perhaps the most significant highlight of the past few months happened on a trip home from a deployment. After completing the build of Siskiyou County, CA’s Pallet shelter village, Jeff learned that his daughter was giving birth.

Thanks to serendipity, Jeff and his teammates were able to navigate from Northern California to Klamath Falls, OR on their journey home to meet his granddaughter. He got the chance to hold her in his arms just hours after she was born. He’s already looking forward to visiting again soon.

“It worked out awesome,” he says. “It’s a blessing. Family is what it’s all about.”

With his tireless work ethic and clear vision for the future, we feel lucky to have Jeff as part of the Pallet team and are eager to see what he accomplishes next.

Meet the other three featured participants in Pallet’s Career Launch PAD and read their stories.

After experiencing heartbreaking loss and facing the task of rebuilding her life, Christa has her eyes set on giving back and creating a brighter future for her daughter.

Christa is no stranger to dedication and discipline. Starting at age three, she played soccer in select club leagues with dreams of someday playing at a professional level.

“It’s literally all I did: practice five days a week and then tournaments on the weekends,” she remembers. “So that was my passion.”

Between soccer training and attending a private Christian school, Christa’s childhood was regimented and predictable (she defines it as “sheltered”). This changed when she turned 15 and left her mother’s house to move to Mill Creek. In high school she became fast friends with a group that regularly drank and smoked cannabis. And after being accepted into this crowd, her life changed drastically.

“I had my first sip of alcohol when I was 15 and within three months I was addicted to opiates,” she says. “And that went on my whole life.”

During this period, Christa was swept up in a cycle of using and selling substances.

“I was addicted to that lifestyle, selling drugs and just living a really chaotic life.”

When she was 17, she met her partner. She got her own apartment a year later. After several years together entrenched in the only lifestyle they knew, they had a daughter.

Not long after becoming a mother, Christa was turned in on substance distribution charges and served six years in prison. Although the experience changed her, it wasn’t until early 2024 when her life took a sudden and unexpected turn.

Christa was in jail for two weeks on account of a DOC violation when a sergeant delivered the news that her partner had been involved in a motorcycle accident and had passed away. The remainder of her sentence gave her the opportunity to detox, and more importantly, wrap her head around the devastation of losing her partner.

“It gave me 10 days to process it and think about our daughter who's already grown up in that lifestyle,” she explains. “And just thinking about what she's going through and how selfish that would be for me to get out and do the same thing. And so I got released and I never got high again.”

Around this time an acquaintance had applied to Pallet to work on the production floor. Unsure of her next steps, Christa followed suit and submitted her own application. Within days of her interview, she started her new job.

Despite being apprehensive of starting a completely unfamiliar lifestyle and career, Christa dove in headfirst and gave it her all.

“I was so unsure of what I wanted to do and what my future looked like or even how to live a normal life,” she says. “And so I just woke up every day and came here, and every week I felt stronger.”

Between the structure of participating in Pallet’s Career Launch PAD and the accepting, supportive environment of working alongside others with similar lived experience, she knew she had found the right fit.

“Being previously incarcerated and having a record, you're judged everywhere you go,” she explains. “A lot of doors close when you have a record, and coming here and having people not only be accepting of that in second chances, but to support recovery in addition is kind of unheard of in the workplace. And I mean, that's probably one of the biggest reasons I ended up staying. So this place definitely has saved my life.”

In a short time, Christa’s tenacity and work ethic has already placed her on a fast track for growth. She jumped on the opportunity to join Pallet’s Safety Committee. She’s taking the skills she’s already learned in the pre-apprenticeship program—like power tool operation, safety protocols, and earning her OSHA certificate—to pursue a career as an electrician upon graduation. She’s particularly proud to be part of the deployment team, traveling to different sites across North America and helping build shelters for people displaced by natural disasters and those experiencing homelessness.

“Being able to give back has been huge for me,” she says. “Because all I've ever done is just tear up my community, and so to be able to go out there and help people get off the streets and be a part of something bigger than me is huge.”

Christa’s hard work, commitment to sobriety, and vision for the future have already improved her relationship with her daughter. She says it feels amazing to be able to be more present and to focus on being a good mom. And although they’re both still processing grief, Christa is trying her best to keep things in perspective.

“I miss him every day,” she says. “Our lives will never be the same. But everything happens for a reason, and I’m trying to think of it like that instead of being depressed. It’s given our daughter a chance.”

Given how far she’s already come, we couldn’t be more proud to have Christa on our team—and we can’t wait to see where she goes next.

Christa's Progress Update: January 2025

Reflecting on enrolling in Pallet’s Career Launch PAD, Christa recalls her driving force to make progress and improve her life.

“I was excited about it because I want to take every possible opportunity that I can get that will move me forward,” she says. “I’ve been excited about it the whole time, I’m just trying to always give it 100 percent.”

Now four months in, she hasn’t lost an ounce of motivation to build her future with her newfound skills.

“So far, it's really helped build my confidence and give me an idea of what I actually want to do with my life because I wasn't really sure,” she says. “For me, having a legal job is the first step. And then going to school has given me some direction and made me feel more positive about what I’m doing with my life.”

Since the beginning of the program, Christa and her classmates have earned certifications for OSHA safety, CPR, operating a boom lift, telehandler, and scissor lift, and even learned how to properly operate a jackhammer.

“Driving the scissor lift and boom lift was really big for me, because I had never even been on either,” she says.

Christa still has her sights set on becoming an electrician after graduating. She says the comprehensive structure of the courses at CITC has been helpful in visualizing outcomes and understanding how she’ll apply this knowledge in her career.

“We go through the textbook, but every week we learn something new so we get a better idea of everything that’s offered,” she explains. “One of the instructors handed out a test that you would take to get your electrician license. So to take that and then see exactly what you need to learn is pretty cool, because it’s a hard test, and I feel like I have something to work toward now.”

Despite being anchored by her dedication and clear vision for the future, Christa has still encountered challenges along the way as she began her recovery journey, a new job, and a pre-apprenticeship program all at the same time. She says it’s been difficult adjusting to new financial burdens, working as hard as she can and still feeling behind on her obligations. Even so, she persevered and told herself quitting wasn’t an option.

“I know I can get through it, I would never give up—that’s definitely not the problem, but I ran into some obstacles for sure,” she says. “Staying focused on my end goal and just making sure I’m a good example to my daughter keeps me going through any obstacles.”

The past few months have had a substantial impact on Christa’s life and outlook. The only thing that’s remained constant is her determination and tenacity to keep going.

“It’s like day and night the way my life has changed,” she says. “Everything about my life is completely different. I’m just getting to know myself because this is the first time I’ve been sober in about 20 years. So I’m just figuring out what my hobbies are, and I’m earning more trust with my family so I can have my daughter back full time. Having this job and being in school allows me to be able to do that.”

Christa's Progress Update: March 2025

It’s been three months since Christa updated us on her progress in Pallet’s Career Launch PAD. Considering how busy she’s been between work, school, and starting the process of finding an apartment of her own through Housing Connector, it seems like that time has flown by.

Christa is still motivated to pursue a career in HVAC or electrical. She said the initial mathematics courses in CITC focused on these trades were challenging, but she found she enjoyed it once it started to click.

“They taught us about volts and different equations, how you can figure out which wire you need and how much electricity a certain load center or whatnot can take,” she explains. “So, it's a lot of math. It was a little intimidating at first, but after she explained it and once you get a couple down you start feeling more confident. And then it was actually kind of fun figuring it out.”

While she’s planning on proactively applying to unions and exploring other pathways to these fields, she’s also keeping an open mind to other options. While participating in the program’s recent project of building a doghouse from the ground up, she even discovered an interest in roofing.

“We got to learn blueprints and floor plans, and then he'd show us how to do the walls, and then how to do the roofs,” she says. “And we got to do a really small scale of a roof. I kind of enjoyed that, actually. Doing that made me think, I don't know, maybe I'll look into roofing! It was kind of fun. I'm gonna be more open to the different options out there and give myself a chance to see if I might enjoy something else.”

Being so busy between work, school, everyday obligations, and spending quality time with her daughter, Christa says it can be challenging to keep up. But she’s making it work.

“It’s just time management and prioritizing my schedule because I have so many things going on,” she shares. “So I'm just learning how to use a day planner and be on time for everything. Staying organized has been a work in progress, but it's going well.”

For now, Christa is set on finishing the CITC courses strong and looking toward the future. With the positive attitude, determination, and strong work ethic she’s demonstrated throughout her time at Pallet, we know there’s no limit on what she can achieve.

“I think it's exciting to complete this because now we're just one step further in attaining our goals,” she says. “I’m just grateful for the opportunity to go through this program and learn new skills that will help me continue bettering my life.”

Meet the other three featured participants in Pallet’s Career Launch PAD and read their stories.

Housing stability is at the core of substance use recovery. The proven success of supportive housing models illustrates the urgent need to expand such programs.

Housing insecurity and substance use disorder are two of the most prevalent public health issues facing our country: people experiencing homelessness (PEH) or housing instability and individuals living with substance use disorders (SUDs) are equally at risk of poor health outcomes. And while the link between the two may be evident to many, recognizing that housing is healthcare—and how it has a crucial impact on people’s recovery journeys—is still overshadowed by insurmountable barriers to stable housing.

The present shortage of attainable housing (only 34 affordable and available rental homes exist for every 100 cost-burdened renters across the country) becomes even more narrow for people with histories of addiction. Beyond prohibitively long waiting lists and a stark lack of supply, federal policies allow housing agencies and landlords to prevent people with past histories of drug use from receiving housing assistance. These realities lead to a problem that is cyclical in nature: once an individual experiences homelessness due to a substance-related incident, they encounter higher difficulty obtaining housing, and, in turn, this lack of secure housing acts as a barrier to recovery and achieving sobriety.

Expanding existing affordable and supportive models alongside reforming policies that prevent people with addiction history from attaining housing is critical to help people in active recovery. These initiatives, coupled with the fundamental understanding that every person’s recovery journey is unique and requires different resources, can effectively build a system that supports those living with SUD and creates equitable housing opportunities for everyone.

The Importance of Recovery Housing Models

The most common housing models that are specifically created to facilitate recovery from SUD are known as transitional housing, permanent supportive housing, and sober living or recovery housing.

While each program structure varies regarding employment or rent contribution requirements, all are focused on providing an environment that prioritizes services, peer support, and accountability. Looking at the big picture, these models are designed to prolong sobriety and provide pathways to permanent housing stability and employment for participants.

In addition to stable housing being one of the four major dimensions of recovery, ample research shows the efficacy of these programs. Positive outcomes among participants include decreased substance use, reduced likelihood of return to use, lower rates of incarceration, higher income, improved employment, and healthier family relationships.

Despite the proven effectiveness of these models, various factors contribute to a shortage of recovery housing programs for people who need them most.

The Need for Expansion

The dearth of recovery and sober living houses with available space threatens the safety and well-being of impacted individuals and their communities. With sky high property and construction prices, as well as insufficient funding and a lack of developable land, building more units that can accommodate these vulnerable groups has become unattainable.

Travis Gannon, founder of sober living organization Hand Up Housing in Snohomish County, attests to this. “It’s tighter than it’s ever been for us,” he says. “I mean, we don’t have openings. We fill everything that we have and we’re turning away 30 to 50 people a week at this point.”

Pallet team member Gabby Bullock has found life-changing support and growth through living at one of the organization’s recovery houses. After six months of participating in the program and being able to reunite with her children, she said: “It just really proves that what I’m doing is the right thing,” she said. “I know that if I’m doing the right thing that more miracles will happen.”

Weld, a Seattle-based nonprofit that provides transitional housing, employment opportunities, and community reconnection for its members, has seen similar successes unfold first-hand. Since launching, the organization has served more than 1,000 system-impacted individuals reenter their community from incarceration, homelessness, and addiction. By creatively utilizing vacant or underutilized properties as transitional housing units and working closely with diversion programs such as King County Drug Diversion Court, Weld offers members housing stability, recovery support, and the chance to build a brighter future for themselves.

The Role of Lived Experience in Peer Support

For Weld Housing Director Jody Bardacke, the organization’s success ultimately comes down to two principles: “attention and effort.”

Bardacke understands that recovery and reentry will look different for each member. People have different backgrounds, experiences, and support needs. Lengths of stay in the program will differ.

“We provide opportunities,” he says. “The amount of time you spend with us, it’s completely immaterial as long as you get what you need. The only part that matters is that you get where you need to go.”

This perspective is informed by Bardacke’s own recovery journey. To him, transitional housing played a pivotal part in his progress: “The day that I got into transitional housing is the same day that I was about to be homeless. If I hadn’t gotten the call that afternoon that I had a bed, I was gonna hit the streets.”

Although there are a variety of reasons people begin using substances, Bardacke points out that SUD among people experiencing homelessness often begins out of necessity, either as a way to stay awake or to numb the discomfort of living unsheltered. Even though the myth that addiction is the most common direct cause of homelessness has been proven false through research, the close relationship between the two contributes to a lasting stigma.

“A lot of times it’s a coping mechanism: you start using because you’re in a tent,” he says. “It’s freezing, and you’re unsafe and you’re stressed out. And when that’s your entire existence, even five minutes of relief is a lot.”

Bardacke realizes the tailored approach he takes to communicate to each Weld member is formed by his own lived experience with SUD and recovery.

“I'm not sitting down with someone talking about, theoretically, what recovery can do for your life,” he says. “I can tell you exactly what recovery can do. I can tell you exactly what transitional housing did for my life. I can tell you about all the different ways that I stumbled along the way and what I did to get through that.”

Creating a Path to Brighter Futures

These success stories illustrate the urgent need to expand attainable, stable housing for people with SUD. Recovery becomes achievable with housing, peer support, and connection to essential services. If a sharper focus is placed on reforming policy, practices, and funding streams and embracing innovative and trauma-informed housing models, a pathway to sustainable recovery will open for these vulnerable groups and their communities.

Data collected from sites across the country shows how the Pallet village model helps residents transition to more permanent solutions.

Every person’s journey to permanent housing is different. The trauma of displacement means every individual encounters their own barriers to finding a stable place to call home. And once someone exits this continuum of care that includes congregate and non-congregate shelter, supportive housing, and other forms of assistance, their success story often goes undocumented.

Although it is challenging to track a person’s progress through the housing continuum with accuracy and consistency, it is crucial to seek out this information and ensure our approach is effective. Pallet’s mission is to provide the supportive environment needed for displaced populations to move onto permanent housing, and this data tells us if our model is working and how we can improve our methods to best suit the needs of every village resident.

Establishing an Open Dialogue is Key

Our partnerships with village service providers are essential in both tracking residents’ progress and gathering context for what resources are needed in each unique community. Site locations across North America are faced with specific root causes of displacement, meaning there is no “one size fits all” solution. This is why once a village is built, our work isn’t finished: details like ongoing operations, maintenance needs, and supportive service provision all tell a distinct story that informs the future of Pallet.

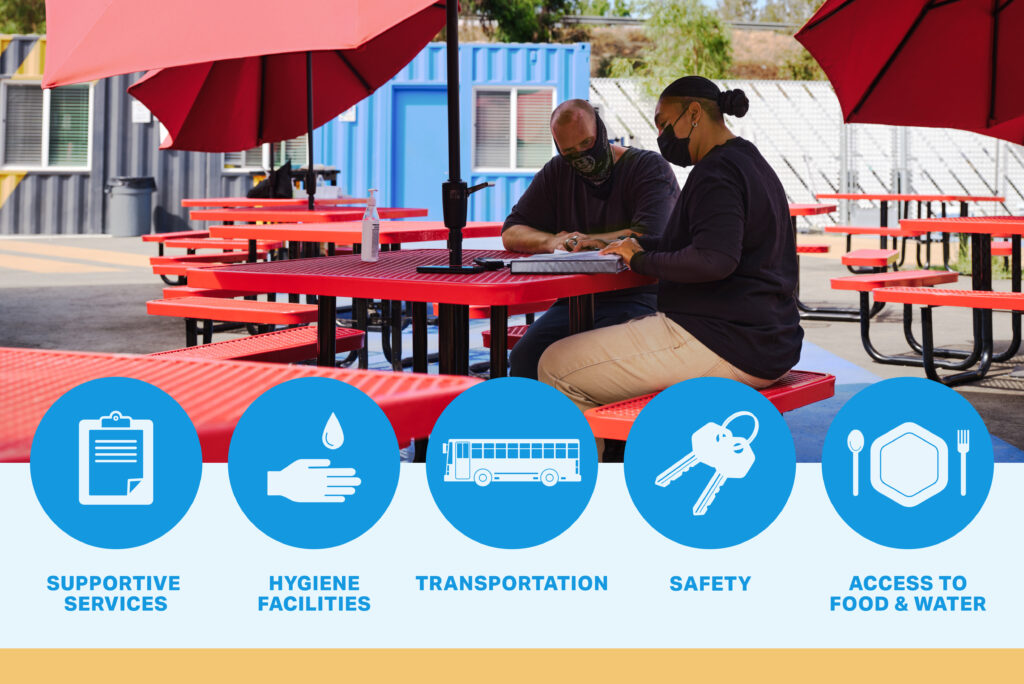

Survey responses from village operators show that on an average day, 10 people move from an existing Pallet village to permanent housing. This tells us that in a broad sense, the pairing of dignified shelter with wraparound services like food and water, hygiene facilities, healthcare, counseling, and employment placement programs are effective in equipping residents with the tools necessary to transition to more permanent solutions. This trend works out to 3,200 expected transitions per year.

Measurable Success

Our ongoing relationships with service providers also bring to attention success stories like Tim’s, who found his own apartment after living in the Salvation Army Safe Outdoor Space in Aurora, CO. Connections to a state-sponsored pension program via onsite staff and help from the Aurora Housing Authority were instrumental in leading Tim to his own home, showing an effective model tailored to the individual needs of each resident.

Vancouver, WA’s approach to address their homelessness crisis, centered on a robust scope of resident services, has also proven success in helping vulnerable individuals on the path to housing. Their first Safe Stay community, The Outpost, reported 30 people moving to permanent housing since opening. Meanwhile, Hope Village achieved 14 transitions in their first year of operations, attributing resident success to a compassionate, healing communal environment with resources including meals, food bank deliveries, clothing, transportation, and assistance obtaining legal identification.

A Way Forward

Aurora and Vancouver are just two examples of sites that have experienced success with the Pallet village model. We believe that while interim shelter is a crucial part in creating safe spaces for vulnerable people to stabilize, it takes a breadth of additional support. This is why we view our product development through the lens of trauma-informed design and lean on our lived experience workforce for perspective: to ensure we are continuing to refine our mission to serve displaced communities to the best of our ability.

By investing in this approach and making concerted efforts toward inclusive wraparound services, any city has the potential to provide displaced populations with pathways to stable and permanent housing.

Understanding the differences between affordable and attainable initiatives is key to a future of stable, equitable housing.

Skyrocketing rental prices, astronomical interest rates, insufficient supply: the severe lack of affordable housing options is not a new development. As of March 2023, a shortage of 7.3 million affordable rental homes was reported, disproportionately affecting low- and extremely low-income families and individuals.

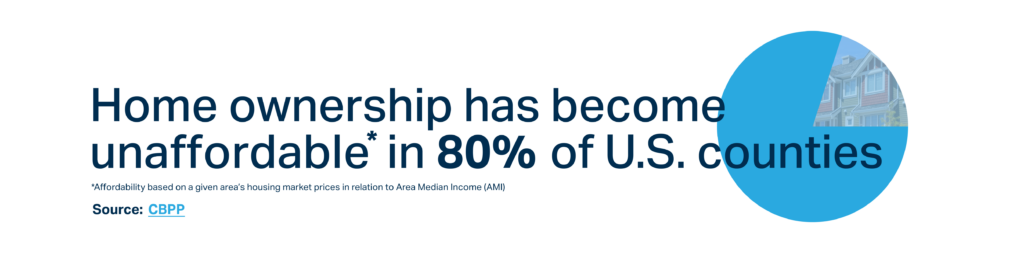

Housing affordability has become a chronic challenge—homeownership has been deemed unaffordable in 80 percent of U.S. counties—prompting policymakers to address this crisis through a variety of affordable housing initiatives. But to make a true impact on housing initiatives, understanding the distinction between "affordable" and "attainable" housing is crucial. While affordable housing targets specific income brackets, attainable housing places a focus on removing a slew of barriers and bringing suitable options within reach for a wider demographic.

Challenges in Housing Attainability

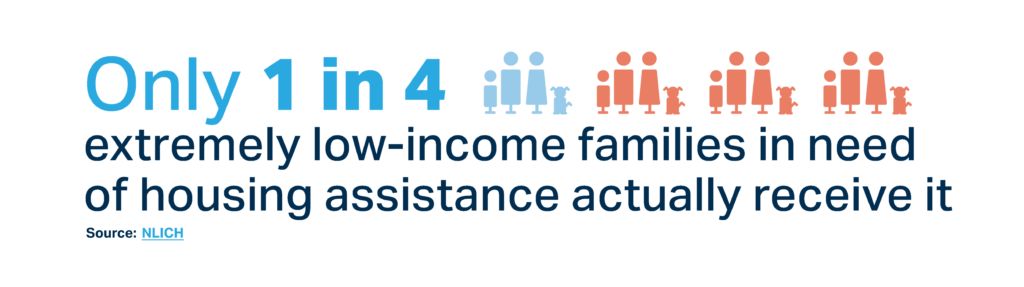

Despite numerous federal programs aimed at providing affordable housing, a significant gap exists between demand and available support. Strict eligibility criteria and additional screening processes often exclude vulnerable populations from assistance: one in four extremely low-income families in need of housing assistance actually receive it. This leaves an estimated 40.6 million Americans burdened by high housing costs, where more than 30 percent of their income is spent on housing and limits their ability to meet basic needs.

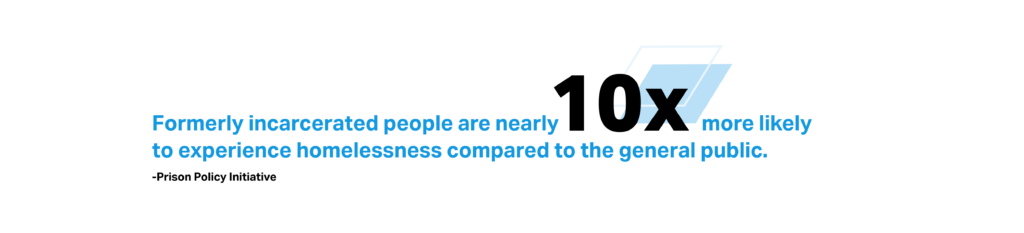

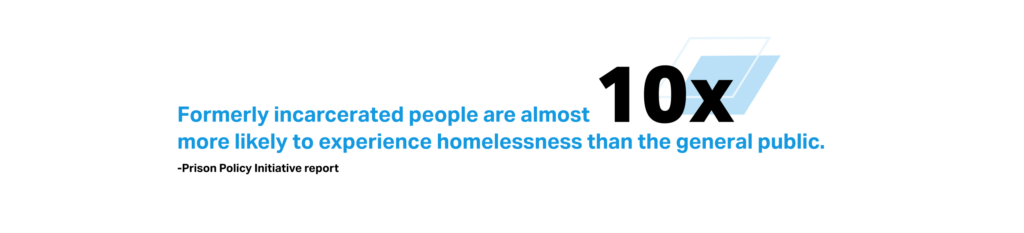

Various systemic barriers, including discriminatory practices and economic thresholds, also hinder a person’s access to attainable housing. Landlord discrimination against housing voucher holders, coupled with restrictive zoning laws, further exacerbates the crisis. Moreover, individuals lacking necessary documentation or with legal system records face significant challenges in securing stable housing.

While housing assistance programs like the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit and the Housing Choice Voucher Program play a crucial role in federal housing strategies, recipients face significant disadvantages including resource limitations and systemic biases. In particular, public housing has experienced a history of mismanagement and underfunding, perpetuating generational patterns of poverty and instability.

Proven Solutions to Improve Housing Attainability

To effectively break the cycle of housing insecurity, a multifaceted approach is necessary. This includes increased government funding, mixed-income housing developments, and expanded access to private capital for developers. Additionally, lowering the multitude of barriers facing vulnerable and low-income populations—accomplished through reforms in zoning laws, enhanced support for renters through federal programs, and amending punitive regulations aimed at formerly incarcerated individuals or those with legal system involvement—is a crucial step toward attainable housing solutions.

By prioritizing attainability, creating innovative partnerships, and developing more inclusive affordable housing initiatives, we can work towards ending housing insecurity while building economic stability and stronger social communities.

To learn more about solutions that address practical, accessible, and attainable housing for all, download our Attainable Housing White Paper.

To ensure our shelter design truly meets the needs of Pallet village residents, we spoke with some of the first people living in our new S2 units to gain feedback and insight from their experience.

The core of Pallet’s mission is to provide safe, secure shelter for people who have experienced displacement and offer a healing environment that helps residents on their next steps toward permanent housing. In developing our innovative S2 product line, we incorporated crucial feedback from our own lived experience workforce and applied key principles of trauma-informed design, knowing that this input is an essential part of creating dignified and comfortable spaces for every Pallet village resident.

Everett Gospel Mission (EGM), a village in our hometown, was the first site to receive 70-square-foot models of our S2 Sleeper shelters. We connected with four residents who had lived in the original shelter designs at EGM and now have moved to S2 units—Kenny, Jimi, Summer, and Erik—to hear their feedback on the new shelters and learn about their stories.

Kenny

Kenny has lived at EGM for nearly two years, originally moving to the site with his friend Libby after losing their housing. He had never experienced homelessness before or spent any time in congregate shelters.

He says since moving to the S2 shelter, he’s noticed the thicker walls have improved insulation and heat retention, reduced condensation, and made the interior more soundproof—a helpful detail since he’s teaching himself to play guitar.

“You don’t hear the rain as much: it’s quieter, way quieter,” Kenny said. “I can be a little louder in the brand new one compared to the old one, because I like to turn the amp up real loud, you know, and play the guitar and stuff. It stays warm in there a lot longer too I’ve noticed. Yeah, it’s overall better.”

Kenny gets along with everyone else living at EGM and doesn’t find it hard to make friends with others in the village. He noted how he likes the residential windows in the S2 unit: him and his neighbor will both open them up and talk from the comfort of their own space.

“It’s kind of cool, because the bed’s right there, so I just open the window and I can talk to the neighbor, and he’ll open his,” he told us. “He bet me four bucks that they would touch if we opened them.”

Kenny easily won that bet.

Jimi

Coming to live at EGM after being hit by a car while crossing the street, Jimi is using his time in the village to focus on sorting out medical issues and navigating a settlement in the case of a broken lease agreement. Sporting a leather jacket and a slick pair of yellow Chuck Taylor’s, he told us he’s grateful to have a temporary space after a tumultuous period of having nowhere to stay and limited means to transport his belongings to a storage space.

“It helps me not have to feel rushed,” Jimi said. “I got a pretty good head injury when I got hit. I don’t remember like I used to. I used to be able to multitask, but now I have to concentrate on one thing. So, being here gives me a chance to plan things, do one thing at a time.”

Jimi mentioned the new unit offers a calmer environment because it’s quieter.

“The thickness of the walls really makes a difference as far as noise,” he said.

Being able to store and arrange his belongings neatly with the integrated shelving is also a plus.

“[There is] a good place to hang your clothes,” Jimi said. “They have little shelves and a place to put hangers and stuff. That’s a lot better. Feels like you can organize your stuff a little easier.”

Summer

Experiencing homelessness for four years before moving into EGM, Summer has been a resident of the village since it opened. She finds comfort in decorating and caring for her plants and flowers, a hobby she picked up since moving into the community. She even arranged planters in communal areas in addition to the inside and outside of her own shelter.

“I did all the flowers that are out here and all the gardening and stuff,” Summer said. “I was doing it for myself already and they said, ‘Hey, let’s put in more for everybody,’ so I just ended up doing all of it.”

Summer told us she likes the ability to customize her shelter and make it her own. She’s added extra storage cubes and shelves, as well as hung mobiles she’s made from the ceiling. A mirror, a TV, and, of course, more plants make Summer’s shelter feel cozier and more unique.

“Everybody always is like, ‘Oh my god, your house looks so much different than everybody else’s!’”

She noted the size of the windows, larger bed, and improved heat circulation are notable details that make the S2 unit comfortable.

Overall, Summer said her favorite part of living at EGM is the ability to feel settled and have a space of her own.

“I could sit, you know, and actually stay and decorate it,” she explained. “I can feel comfortable and actually move in and not have to worry about police making me leave or having to drag everything with me. I have a place I can go in and sit down and have room for company and a TV.”

Erik

Erik has only lived at EGM for four months, spending the first two in the original shelter design before moving into the newer model. He said the increased square footage in the S2 unit is a significant improvement in maneuvering his wheelchair, and the larger bed is a better fit for him.

“I can move around a lot better in a wheelchair,” he told us. “To be able to sit in it and turn around makes a huge difference. And the bed is a little bit wider, so I sleep a lot better. It’s lower too, because I was tending to sit up against the bed in the older one. Those made my legs fall asleep and cut my circulation off. With the new style bed, that’s totally better: I can sit up on the edge of the bed and my legs won’t fall asleep.”

He also said the tighter seals on the corner connections and improved insulation from the wall panels helps keep the heat in.

“Having it hold the heat is a big difference too because it makes you feel like you’re in a better structure, since it’s not leaking out the seams.”

When Erik was hospitalized due to heart failure, he lost his housing, his car was impounded, and he found himself living on the streets. This was after working his whole career in the construction industry: first building houses, and then operating his own concrete company. He said it was a shock to exit the hospital and lose so much, along with experiencing displacement for the first time in his life.

Even with this devastating loss and coping with his medical issues, he is appreciative to be part of the community at EGM and have his own shelter.

“I think it’s great and it’s a great program, it’s a great thing [Pallet] is doing making those and making them available for communities to put them in and help people out,” he said. “Because I definitely need help. So it’s a beautiful thing what you guys are doing, because when people need help, you’re part of the solution.”

To learn more about how the design of our S2 shelters was informed by those with lived experience, read our blog.

All the details that come together to make our new S2 shelter line were inspired and informed by feedback from our own lived experience workforce.

One of Pallet’s foundational elements is our lived experience workforce. As a fair chance employer, we provide opportunities for people who have experienced homelessness, recovery from substance use disorder, and involvement in the criminal legal system to build their futures.

We often talk about how our approach to designing Pallet shelters and implementing them within a healing community village model is informed by those with lived experience. In developing our S2 shelter line within the lens of trauma-informed design, these voices were crucial to ensure that our shelters provide private, safe, and dignified living spaces for displaced populations and encourage positive housing transitions.

There are many seemingly minute considerations that influenced the design of our S2 Sleeper and EnSuite models. To capture how important these details truly are for village residents, we gathered Pallet’s first Lived Experience Cohort—Josh, Alan, Sarah, and Dave—to describe in their own words how each design aspect is significant for anyone who has experienced the trauma of displacement.

Comfort

Significant changes in aesthetic, functionality, and fixtures make the S2 line a more comfortable living space overall. Smooth wall panels make the interior of each shelter more welcoming.

“The biggest thing is the aluminum [interior flashing] is gone,” says Josh. “So it feels like a home. It seems like someone took time to make it.”

When Josh was in Sacramento on Pallet’s California Roadshow, he noticed how attendees felt while touring S2 shelters.

“Almost everyone who walked in said, ‘This feels very warm. It’s so inviting to walk in here, it’s so open.’”

Dave comments on the effect this feeling would have on someone who has experienced homelessness.

“One of the most disturbing things to me when I was out there was coming to that realization: ‘I don’t have a f***ing home anymore,’” he recalls. “And to go into something that feels like a home, that you can call your little home, that’s really nice. That’s huge.”

Residential windows are another significant detail that Sarah notes.

“They give more lighting, so it doesn’t feel like a jail cell,” she says.

“They’re way better windows,” Dave adds. “[Residents] have a big, nice window to look out of now.”

Installing larger beds was also a noted concern, and the Twin XL is a more inclusive option.

“I think the larger sized mattresses are great,” she says. “Now villages can get twin sheets and covers and protective sheets that fit. And the fact that these new mattresses are waterproof, even the threading on the seams.”

The S2 EnSuite is Pallet’s first sleeping shelter with integrated hygiene facilities. Josh says the opportunity to have this kind of space with access to his own bathroom would have been a significant aid in his recovery journey.

“If I moved into the EnSuite, that would have blown my mind,” he quips. “If I was coming off the street or living in my Explorer like I was at the time, and moved into that, I might have been clean way sooner. Because it would’ve given me some hope that somebody cared.”

Safety Features

Pallet’s in-house engineering team created the S2 shelter line with safety at its core. In addition to the structurally insulated panels that offer durability and robust wind, fire, and snow load ratings, the elimination of exposed hardware in the interior is another detail that ensures safety for residents of all ages and walks of life.

Input from our lived experience team and feedback from Pallet village residents across the country also led to tweaks to the included fixtures, reducing the likelihood of essential safety functions being disarmed or damaged.

“We were pushing to get a cage over the smoke alarm, or something to prevent people from taking them off,” Sarah remembers. “Now [with the hardwired connection] you can’t shut off the power to the smoke alarm.”

The consideration that displacement affects different communities—from single residents with pets to families with young children—also influenced changes in other design elements of the S2 that may have gone unnoticed otherwise.

“I think the electrical panel is better: now we have the breakers on the outside and the plugs on the inside,” Josh adds. “So it keeps you from wanting to easily tamper with it.”

Dignity

Offering a more customizable layout and built-in wire shelving in the S2 line creates a dignified space for every Pallet shelter resident.

“Having a place to hang up clothes, that’s something I heard a lot when I was talking to residents in California,” Sarah comments. “That was a huge improvement, because if you’re still having to constantly live out of your bags and your suitcase, you’re not moving forward to get out of that survival mode.”

The ability to freely move the bed and desk is also a significant detail for people who have experienced institutional or congregate shelter settings.

“If I saw the bed set up in between two windows, I would say, ‘There’s absolutely no way I would pass out in between in between two windows,’” Alan quips. “I would sleep underneath the bed maybe. Because people walking past the windows, it just doesn’t make me feel very safe.”

Sarah agrees: “And then too, if you want to rearrange or just make it your own, everyone’s going to have a different feel of where they want to sleep on any given day. It gives you freedom. And if you have the freedom to live how you want to live, it gives you the sense of self-sufficiency rather than having to follow all the strict congregate shelter rules.”

Josh further highlights how significant this feeling of freedom can be when looking back on his own experiences.

“See, I would have never moved it, but having the opportunity to move it is a big thing,” he says. “Because when you’re in jail, your bed is where it is. Your seat is where it is. There’s no moving it around, so being able to move your house around like anyone else, it makes you feel more like a human being.”

Ultimately, our Lived Experience Cohort members agree that implementing these changes to create the S2 line advances our mission to help displaced populations transition to more permanent solutions.

“In the future when we come out with new products, it’ll probably be like, ‘Oh wow, I didn’t really think of this before,’” Josh offers. “But right now I think this is the best we can do. It really is, until we get more feedback on what the next thing is.”

“We are providing that space for people to take the next step,” Sarah replies. “We can’t personally give good wraparound services because that’s not our thing, but we can provide the environment for it. It takes all these little things to get out of survival mode, but the first step is to get off the streets, and that’s where we start. It takes a village to help a village.”

Adopting the principles of trauma-informed design is a crucial framework for creating a safe, supportive, and healing environment in every shelter we build.