From launching a new product to expanding our footprint and creating our new workforce model, it was an eventful year at Pallet. Read on for our top stories of 2024.

As we look back on 2024, we are both proud of our advancements in providing safe, secure spaces for unsheltered populations and motivated to keep pushing forward. Even as we passed 5,000 shelters built in North America, expanded our reach into Canada, and released a new innovative product line to offer faster deployment and comfort for residents, the human displacement crisis persists—encouraging the Pallet team to continue working tirelessly until everyone has a stable place to call home.

Here's a round-up of our top stories from this year.

1. Pallet Hits the Road in California

Kicking off the year, the Pallet team embarked on a roadshow through California to showcase our new S2 product line and meet people working on the ground in their communities to solve their local displacement crises. We stopped in 11 different cities from Sacramento all the way to Los Angeles, displaying our S2 units and demonstrating the positive impact Pallet has made for unhoused communities across North America. [Keep Reading]

2. Launching Our S2 Shelter Line

Featuring an innovative panel connection system enabling even faster deployment, improved safety features, and increased comfort for residents, our S2 line is the next evolution of our in-house engineered and manufactured shelter products. Every decision we made in developing these new products was informed by input from residents living in Pallet shelters across the country and our own lived experience workforce. [Keep Reading]

3. Pallet's First Canadian Site Opens in Kelowna

Offering 60 individual shelter units for people experiencing homelessness in Kelowna, BC, STEP Place is Pallet’s first community installed in Canada. The City of Kelowna partnered with the Province of British Columbia and BC Housing to provide safe, secure spaces for people to stabilize and access onsite services provided by John Howard Society of Okanagan and Kootenay.

“We recognize the immediate need to bring unhoused people in Kelowna indoors and provide them the care they need,” said Ravi Kahlon, Minister of Housing. “Through this housing, people experiencing homelessness can be supported as they stabilize and move forward with their lives.” [Keep Reading]

4. Denver Opens First Village of S2 Shelters

Just in time for the New Year and part of Mayor Johnston’s plan to house 1,000 unhoused Denver residents by 2025, the opening of the city’s first micro-community also marked the first site comprising Pallet’s S2 Sleeper shelters.

“This is such a symbol of what we wanted to create,” said Cole Chandler, the mayor’s homeless czar. “It wasn't just about getting people indoors, but it's about bringing people back to life and helping people thrive. And you see that in this space.” [Keep Reading]

5. Introducing Our Purpose-Led Workforce Model

From the very beginning of Pallet, we have placed our team members at the core of our mission to give people a fair chance at employment. The majority of our staff have lived experience of homelessness, incarceration, recovery from substance use disorder, or involvement in the criminal legal system. With our Purpose-Led Workforce Model, we are taking the next step in helping our team grow and advance their careers. [Keep Reading]

6. Public-Private Collaboration in Santa Fe

Working together, the City of Santa Fe and Christ Lutheran Church opened the state’s first micro-community of its kind to provide shelter and supportive services for unhoused New Mexicans.

“It takes a community working together to really solve the challenge of homelessness, and that is our aim: to have zero homelessness in Santa Fe,” said Mayor Alan Webber. “We will keep working to make sure the people who are homeless in Santa Fe are housed, safe, secure, with respect, dignity, and with services.” [Keep Reading]

7. Tonya: "I feel like I'm doing something worthwhile"

Tonya knows Everett like the back of her hand. She spent most of her childhood on the north side of town but has lived in various neighborhoods throughout her life. So it seems fitting that now, after a decade of living on the streets of her hometown, she’s found a new path at Pallet and already moved into a place of her own mere steps away from HQ.

As one of the first participants in Pallet’s Career Launch PAD (Program for Apprenticeship Development), Tonya and her classmates are starting on the path to building independence and a brighter future for themselves. [Keep Reading]

8. Pallet Provides Shelter in Response to Hurricanes Helene and Milton

In rapid response to the disasters sustained in Florida following two major hurricanes, the Pallet deployment team jumped into action to build 50 shelters to help people get displaced by Helene and Milton get inside to safety.

By working closely with Pasco County administrators, county commissioners, facilities departments, and Catholic Charities, we were able to deploy and assemble the shelters mere days after the storms passed. [Keep Reading]

9. Connecting Pallet Team Members with Housing

At Pallet, our people are our purpose. Giving people a fair chance at stable employment and creating a supportive environment that fosters wellness and growth for all our team members is a crucial part of our mission.

A key part of this is ensuring that everyone on our team has all the tools and resources they need to succeed. In our work building shelter communities for displaced populations across North America, we know firsthand how having a safe, stable place to live is not only a basic human right—it is also the foundation for maintaining health, helping those with substance use disorder on their recovery journeys, and healing trauma.

That’s why we are proud to have become a Community Partner with Housing Connector, an organization that helps find housing for marginalized individuals and families. In our first year of the partnership, Housing Connector has been instrumental in finding housing for 4 Pallet team members by removing barriers and locating available properties. [Keep Reading]

Data collected from sites across the country shows how the Pallet village model helps residents transition to more permanent solutions.

Every person’s journey to permanent housing is different. The trauma of displacement means every individual encounters their own barriers to finding a stable place to call home. And once someone exits this continuum of care that includes congregate and non-congregate shelter, supportive housing, and other forms of assistance, their success story often goes undocumented.

Although it is challenging to track a person’s progress through the housing continuum with accuracy and consistency, it is crucial to seek out this information and ensure our approach is effective. Pallet’s mission is to provide the supportive environment needed for displaced populations to move onto permanent housing, and this data tells us if our model is working and how we can improve our methods to best suit the needs of every village resident.

Establishing an Open Dialogue is Key

Our partnerships with village service providers are essential in both tracking residents’ progress and gathering context for what resources are needed in each unique community. Site locations across North America are faced with specific root causes of displacement, meaning there is no “one size fits all” solution. This is why once a village is built, our work isn’t finished: details like ongoing operations, maintenance needs, and supportive service provision all tell a distinct story that informs the future of Pallet.

Survey responses from village operators show that on an average day, 10 people move from an existing Pallet village to permanent housing. This tells us that in a broad sense, the pairing of dignified shelter with wraparound services like food and water, hygiene facilities, healthcare, counseling, and employment placement programs are effective in equipping residents with the tools necessary to transition to more permanent solutions. This trend works out to 3,200 expected transitions per year.

Measurable Success

Our ongoing relationships with service providers also bring to attention success stories like Tim’s, who found his own apartment after living in the Salvation Army Safe Outdoor Space in Aurora, CO. Connections to a state-sponsored pension program via onsite staff and help from the Aurora Housing Authority were instrumental in leading Tim to his own home, showing an effective model tailored to the individual needs of each resident.

Vancouver, WA’s approach to address their homelessness crisis, centered on a robust scope of resident services, has also proven success in helping vulnerable individuals on the path to housing. Their first Safe Stay community, The Outpost, reported 30 people moving to permanent housing since opening. Meanwhile, Hope Village achieved 14 transitions in their first year of operations, attributing resident success to a compassionate, healing communal environment with resources including meals, food bank deliveries, clothing, transportation, and assistance obtaining legal identification.

A Way Forward

Aurora and Vancouver are just two examples of sites that have experienced success with the Pallet village model. We believe that while interim shelter is a crucial part in creating safe spaces for vulnerable people to stabilize, it takes a breadth of additional support. This is why we view our product development through the lens of trauma-informed design and lean on our lived experience workforce for perspective: to ensure we are continuing to refine our mission to serve displaced communities to the best of our ability.

By investing in this approach and making concerted efforts toward inclusive wraparound services, any city has the potential to provide displaced populations with pathways to stable and permanent housing.

Understanding the differences between affordable and attainable initiatives is key to a future of stable, equitable housing.

Skyrocketing rental prices, astronomical interest rates, insufficient supply: the severe lack of affordable housing options is not a new development. As of March 2023, a shortage of 7.3 million affordable rental homes was reported, disproportionately affecting low- and extremely low-income families and individuals.

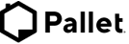

Housing affordability has become a chronic challenge—homeownership has been deemed unaffordable in 80 percent of U.S. counties—prompting policymakers to address this crisis through a variety of affordable housing initiatives. But to make a true impact on housing initiatives, understanding the distinction between "affordable" and "attainable" housing is crucial. While affordable housing targets specific income brackets, attainable housing places a focus on removing a slew of barriers and bringing suitable options within reach for a wider demographic.

Challenges in Housing Attainability

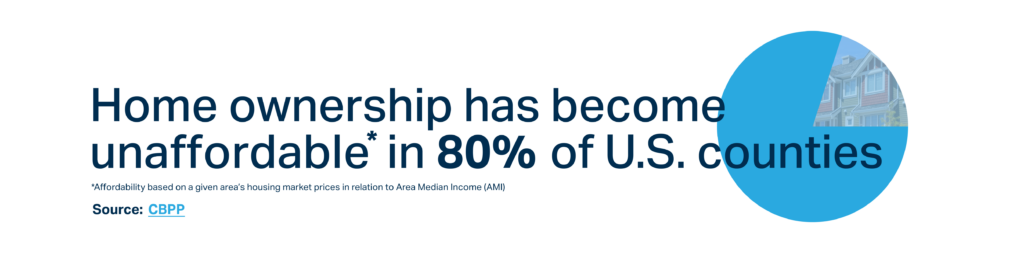

Despite numerous federal programs aimed at providing affordable housing, a significant gap exists between demand and available support. Strict eligibility criteria and additional screening processes often exclude vulnerable populations from assistance: one in four extremely low-income families in need of housing assistance actually receive it. This leaves an estimated 40.6 million Americans burdened by high housing costs, where more than 30 percent of their income is spent on housing and limits their ability to meet basic needs.

Various systemic barriers, including discriminatory practices and economic thresholds, also hinder a person’s access to attainable housing. Landlord discrimination against housing voucher holders, coupled with restrictive zoning laws, further exacerbates the crisis. Moreover, individuals lacking necessary documentation or with legal system records face significant challenges in securing stable housing.

While housing assistance programs like the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit and the Housing Choice Voucher Program play a crucial role in federal housing strategies, recipients face significant disadvantages including resource limitations and systemic biases. In particular, public housing has experienced a history of mismanagement and underfunding, perpetuating generational patterns of poverty and instability.

Proven Solutions to Improve Housing Attainability

To effectively break the cycle of housing insecurity, a multifaceted approach is necessary. This includes increased government funding, mixed-income housing developments, and expanded access to private capital for developers. Additionally, lowering the multitude of barriers facing vulnerable and low-income populations—accomplished through reforms in zoning laws, enhanced support for renters through federal programs, and amending punitive regulations aimed at formerly incarcerated individuals or those with legal system involvement—is a crucial step toward attainable housing solutions.

By prioritizing attainability, creating innovative partnerships, and developing more inclusive affordable housing initiatives, we can work towards ending housing insecurity while building economic stability and stronger social communities.

To learn more about solutions that address practical, accessible, and attainable housing for all, download our Attainable Housing White Paper.

To ensure our shelter design truly meets the needs of Pallet village residents, we spoke with some of the first people living in our new S2 units to gain feedback and insight from their experience.

The core of Pallet’s mission is to provide safe, secure shelter for people who have experienced displacement and offer a healing environment that helps residents on their next steps toward permanent housing. In developing our innovative S2 product line, we incorporated crucial feedback from our own lived experience workforce and applied key principles of trauma-informed design, knowing that this input is an essential part of creating dignified and comfortable spaces for every Pallet village resident.

Everett Gospel Mission (EGM), a village in our hometown, was the first site to receive 70-square-foot models of our S2 Sleeper shelters. We connected with four residents who had lived in the original shelter designs at EGM and now have moved to S2 units—Kenny, Jimi, Summer, and Erik—to hear their feedback on the new shelters and learn about their stories.

Kenny

Kenny has lived at EGM for nearly two years, originally moving to the site with his friend Libby after losing their housing. He had never experienced homelessness before or spent any time in congregate shelters.

He says since moving to the S2 shelter, he’s noticed the thicker walls have improved insulation and heat retention, reduced condensation, and made the interior more soundproof—a helpful detail since he’s teaching himself to play guitar.

“You don’t hear the rain as much: it’s quieter, way quieter,” Kenny said. “I can be a little louder in the brand new one compared to the old one, because I like to turn the amp up real loud, you know, and play the guitar and stuff. It stays warm in there a lot longer too I’ve noticed. Yeah, it’s overall better.”

Kenny gets along with everyone else living at EGM and doesn’t find it hard to make friends with others in the village. He noted how he likes the residential windows in the S2 unit: him and his neighbor will both open them up and talk from the comfort of their own space.

“It’s kind of cool, because the bed’s right there, so I just open the window and I can talk to the neighbor, and he’ll open his,” he told us. “He bet me four bucks that they would touch if we opened them.”

Kenny easily won that bet.

Jimi

Coming to live at EGM after being hit by a car while crossing the street, Jimi is using his time in the village to focus on sorting out medical issues and navigating a settlement in the case of a broken lease agreement. Sporting a leather jacket and a slick pair of yellow Chuck Taylor’s, he told us he’s grateful to have a temporary space after a tumultuous period of having nowhere to stay and limited means to transport his belongings to a storage space.

“It helps me not have to feel rushed,” Jimi said. “I got a pretty good head injury when I got hit. I don’t remember like I used to. I used to be able to multitask, but now I have to concentrate on one thing. So, being here gives me a chance to plan things, do one thing at a time.”

Jimi mentioned the new unit offers a calmer environment because it’s quieter.

“The thickness of the walls really makes a difference as far as noise,” he said.

Being able to store and arrange his belongings neatly with the integrated shelving is also a plus.

“[There is] a good place to hang your clothes,” Jimi said. “They have little shelves and a place to put hangers and stuff. That’s a lot better. Feels like you can organize your stuff a little easier.”

Summer

Experiencing homelessness for four years before moving into EGM, Summer has been a resident of the village since it opened. She finds comfort in decorating and caring for her plants and flowers, a hobby she picked up since moving into the community. She even arranged planters in communal areas in addition to the inside and outside of her own shelter.

“I did all the flowers that are out here and all the gardening and stuff,” Summer said. “I was doing it for myself already and they said, ‘Hey, let’s put in more for everybody,’ so I just ended up doing all of it.”

Summer told us she likes the ability to customize her shelter and make it her own. She’s added extra storage cubes and shelves, as well as hung mobiles she’s made from the ceiling. A mirror, a TV, and, of course, more plants make Summer’s shelter feel cozier and more unique.

“Everybody always is like, ‘Oh my god, your house looks so much different than everybody else’s!’”

She noted the size of the windows, larger bed, and improved heat circulation are notable details that make the S2 unit comfortable.

Overall, Summer said her favorite part of living at EGM is the ability to feel settled and have a space of her own.

“I could sit, you know, and actually stay and decorate it,” she explained. “I can feel comfortable and actually move in and not have to worry about police making me leave or having to drag everything with me. I have a place I can go in and sit down and have room for company and a TV.”

Erik

Erik has only lived at EGM for four months, spending the first two in the original shelter design before moving into the newer model. He said the increased square footage in the S2 unit is a significant improvement in maneuvering his wheelchair, and the larger bed is a better fit for him.

“I can move around a lot better in a wheelchair,” he told us. “To be able to sit in it and turn around makes a huge difference. And the bed is a little bit wider, so I sleep a lot better. It’s lower too, because I was tending to sit up against the bed in the older one. Those made my legs fall asleep and cut my circulation off. With the new style bed, that’s totally better: I can sit up on the edge of the bed and my legs won’t fall asleep.”

He also said the tighter seals on the corner connections and improved insulation from the wall panels helps keep the heat in.

“Having it hold the heat is a big difference too because it makes you feel like you’re in a better structure, since it’s not leaking out the seams.”

When Erik was hospitalized due to heart failure, he lost his housing, his car was impounded, and he found himself living on the streets. This was after working his whole career in the construction industry: first building houses, and then operating his own concrete company. He said it was a shock to exit the hospital and lose so much, along with experiencing displacement for the first time in his life.

Even with this devastating loss and coping with his medical issues, he is appreciative to be part of the community at EGM and have his own shelter.

“I think it’s great and it’s a great program, it’s a great thing [Pallet] is doing making those and making them available for communities to put them in and help people out,” he said. “Because I definitely need help. So it’s a beautiful thing what you guys are doing, because when people need help, you’re part of the solution.”

To learn more about how the design of our S2 shelters was informed by those with lived experience, read our blog.

All the details that come together to make our new S2 shelter line were inspired and informed by feedback from our own lived experience workforce.

One of Pallet’s foundational elements is our lived experience workforce. As a fair chance employer, we provide opportunities for people who have experienced homelessness, recovery from substance use disorder, and involvement in the criminal legal system to build their futures.

We often talk about how our approach to designing Pallet shelters and implementing them within a healing community village model is informed by those with lived experience. In developing our S2 shelter line within the lens of trauma-informed design, these voices were crucial to ensure that our shelters provide private, safe, and dignified living spaces for displaced populations and encourage positive housing transitions.

There are many seemingly minute considerations that influenced the design of our S2 Sleeper and EnSuite models. To capture how important these details truly are for village residents, we gathered Pallet’s first Lived Experience Cohort—Josh, Alan, Sarah, and Dave—to describe in their own words how each design aspect is significant for anyone who has experienced the trauma of displacement.

Comfort

Significant changes in aesthetic, functionality, and fixtures make the S2 line a more comfortable living space overall. Smooth wall panels make the interior of each shelter more welcoming.

“The biggest thing is the aluminum [interior flashing] is gone,” says Josh. “So it feels like a home. It seems like someone took time to make it.”

When Josh was in Sacramento on Pallet’s California Roadshow, he noticed how attendees felt while touring S2 shelters.

“Almost everyone who walked in said, ‘This feels very warm. It’s so inviting to walk in here, it’s so open.’”

Dave comments on the effect this feeling would have on someone who has experienced homelessness.

“One of the most disturbing things to me when I was out there was coming to that realization: ‘I don’t have a f***ing home anymore,’” he recalls. “And to go into something that feels like a home, that you can call your little home, that’s really nice. That’s huge.”

Residential windows are another significant detail that Sarah notes.

“They give more lighting, so it doesn’t feel like a jail cell,” she says.

“They’re way better windows,” Dave adds. “[Residents] have a big, nice window to look out of now.”

Installing larger beds was also a noted concern, and the Twin XL is a more inclusive option.

“I think the larger sized mattresses are great,” she says. “Now villages can get twin sheets and covers and protective sheets that fit. And the fact that these new mattresses are waterproof, even the threading on the seams.”

The S2 EnSuite is Pallet’s first sleeping shelter with integrated hygiene facilities. Josh says the opportunity to have this kind of space with access to his own bathroom would have been a significant aid in his recovery journey.

“If I moved into the EnSuite, that would have blown my mind,” he quips. “If I was coming off the street or living in my Explorer like I was at the time, and moved into that, I might have been clean way sooner. Because it would’ve given me some hope that somebody cared.”

Safety Features

Pallet’s in-house engineering team created the S2 shelter line with safety at its core. In addition to the structurally insulated panels that offer durability and robust wind, fire, and snow load ratings, the elimination of exposed hardware in the interior is another detail that ensures safety for residents of all ages and walks of life.

Input from our lived experience team and feedback from Pallet village residents across the country also led to tweaks to the included fixtures, reducing the likelihood of essential safety functions being disarmed or damaged.

“We were pushing to get a cage over the smoke alarm, or something to prevent people from taking them off,” Sarah remembers. “Now [with the hardwired connection] you can’t shut off the power to the smoke alarm.”

The consideration that displacement affects different communities—from single residents with pets to families with young children—also influenced changes in other design elements of the S2 that may have gone unnoticed otherwise.

“I think the electrical panel is better: now we have the breakers on the outside and the plugs on the inside,” Josh adds. “So it keeps you from wanting to easily tamper with it.”

Dignity

Offering a more customizable layout and built-in wire shelving in the S2 line creates a dignified space for every Pallet shelter resident.

“Having a place to hang up clothes, that’s something I heard a lot when I was talking to residents in California,” Sarah comments. “That was a huge improvement, because if you’re still having to constantly live out of your bags and your suitcase, you’re not moving forward to get out of that survival mode.”

The ability to freely move the bed and desk is also a significant detail for people who have experienced institutional or congregate shelter settings.

“If I saw the bed set up in between two windows, I would say, ‘There’s absolutely no way I would pass out in between in between two windows,’” Alan quips. “I would sleep underneath the bed maybe. Because people walking past the windows, it just doesn’t make me feel very safe.”

Sarah agrees: “And then too, if you want to rearrange or just make it your own, everyone’s going to have a different feel of where they want to sleep on any given day. It gives you freedom. And if you have the freedom to live how you want to live, it gives you the sense of self-sufficiency rather than having to follow all the strict congregate shelter rules.”

Josh further highlights how significant this feeling of freedom can be when looking back on his own experiences.

“See, I would have never moved it, but having the opportunity to move it is a big thing,” he says. “Because when you’re in jail, your bed is where it is. Your seat is where it is. There’s no moving it around, so being able to move your house around like anyone else, it makes you feel more like a human being.”

Ultimately, our Lived Experience Cohort members agree that implementing these changes to create the S2 line advances our mission to help displaced populations transition to more permanent solutions.

“In the future when we come out with new products, it’ll probably be like, ‘Oh wow, I didn’t really think of this before,’” Josh offers. “But right now I think this is the best we can do. It really is, until we get more feedback on what the next thing is.”

“We are providing that space for people to take the next step,” Sarah replies. “We can’t personally give good wraparound services because that’s not our thing, but we can provide the environment for it. It takes all these little things to get out of survival mode, but the first step is to get off the streets, and that’s where we start. It takes a village to help a village.”

Adopting the principles of trauma-informed design is a crucial framework for creating a safe, supportive, and healing environment in every shelter we build.

When developing and designing Pallet shelters, our top priority is to best serve the needs of displaced populations. This is why we have our dignity standards in place: to ensure that each shelter village provides a positive, supportive community environment for every resident.

But we also understand our responsibility to design our shelters so they offer a private, healing atmosphere for people to plan their transitions to more permanent solutions. It has long been understood that the way we interact with and utilize physical spaces—along with our emotional and psychological reactions to those spaces—are dictated by a wide range of design choices. An airy, open lobby with large windows and ample natural lighting is bound to elicit a completely different response compared to an enclosed, fluorescent-lit office.

Only recently has this concept been integrated into architectural design specifically catered to vulnerable users. With trauma-informed care as a framework, trauma-informed design (TID) seeks to create physical spaces centered around principles like safety, empowerment, and well-being. Building with these concepts in mind can actively aid a person’s development, grow their ability to trust others, and avoid the possibility of re-traumatization.

Experiencing chronic homelessness, coping with substance use disorder, reintegrating into the community after being incarcerated, or suddenly losing your home to a natural disaster are all traumatic experiences. By viewing our product development and engineering processes through the lens of TID and incorporating features that promote healing, inclusion, and stabilization, we aim to provide shelter that supports the needs of those impacted by the trauma of displacement.

Here are some of the ways we applied the four main principles of TID—Safety & Trust; Choice & Empowerment; Community & Collaboration; and Beauty & Joy—in the design of our innovative S2 shelter line:

- Privacy: A key aspect of TID is privacy. When someone moves into a Pallet shelter, they are able to access a personal space of their own with a locking door. For people who have experienced living unsheltered, staying in congregate settings, or being incarcerated, walking through the door with to a private and restful place is a powerful moment.

- Security: In addition to a locking solid core door equipped with a kick plate and peephole, having each shelter as part of a larger community model with onsite security personnel makes residents feel less isolated, even when enjoying the privacy of their own unit. Outside lighting also promotes a feeling of safety for residents of Pallet villages.

- Safety Features: Extensive product testing guarantees that S2 shelters are safe in even extreme conditions—whether it’s wind, snow, rain, or extreme cold. Each unit is equipped with a smoke/CO detector, a fire extinguisher, and an egress window in case of emergency.

- Residential Fixtures: Interior options like a freestanding bed and desk visually separate S2 shelters from institutional settings while allowing for a customizable layout. Features like operable residential windows and LED lighting also help residents minimize associations with environments where they potentially experienced trauma. The S2 EnSuite, Pallet’s first sleeping shelter with an integrated bathroom, includes a toilet, sink, and shower. For vulnerable populations with specific traumatic experiences, access to private hygiene facilities can be a significant step toward healing.

- Climate Control Options: Beyond keeping shelters warm in the winters and cool in the summers, integrated heating and A/C allows residents to freely adjust temperatures to fit their personal preferences.

- Storage and Organization: Integrated shelving and storage space grant residents to safely store their possessions, display meaningful belongings, and organize necessities like clothes and food—bringing a sense of autonomy and respect not found in institutional settings.

- Clean, Simple Aesthetic: Pallet’s patent pending connection system and the structurally insulated panels used in the S2 line allow for smooth exterior and interior walls, creating a warm, inviting environment in each shelter.

Pallet is committed to applying the philosophy of TID in our shelters to accommodate village residents who have lived through trauma. Applying these concepts, along with listening to feedback from real users and our own lived experience workforce, helped us develop the S2 shelter line as our most innovative solution to the crisis of human displacement. We believe that every design detail, no matter how small it may seem, can make a big difference in someone’s journey to permanent housing and reintegration.

To see how S2 shelters provided rapid shelter and warmth for unhoused Denver residents by the New Year, read our case study.

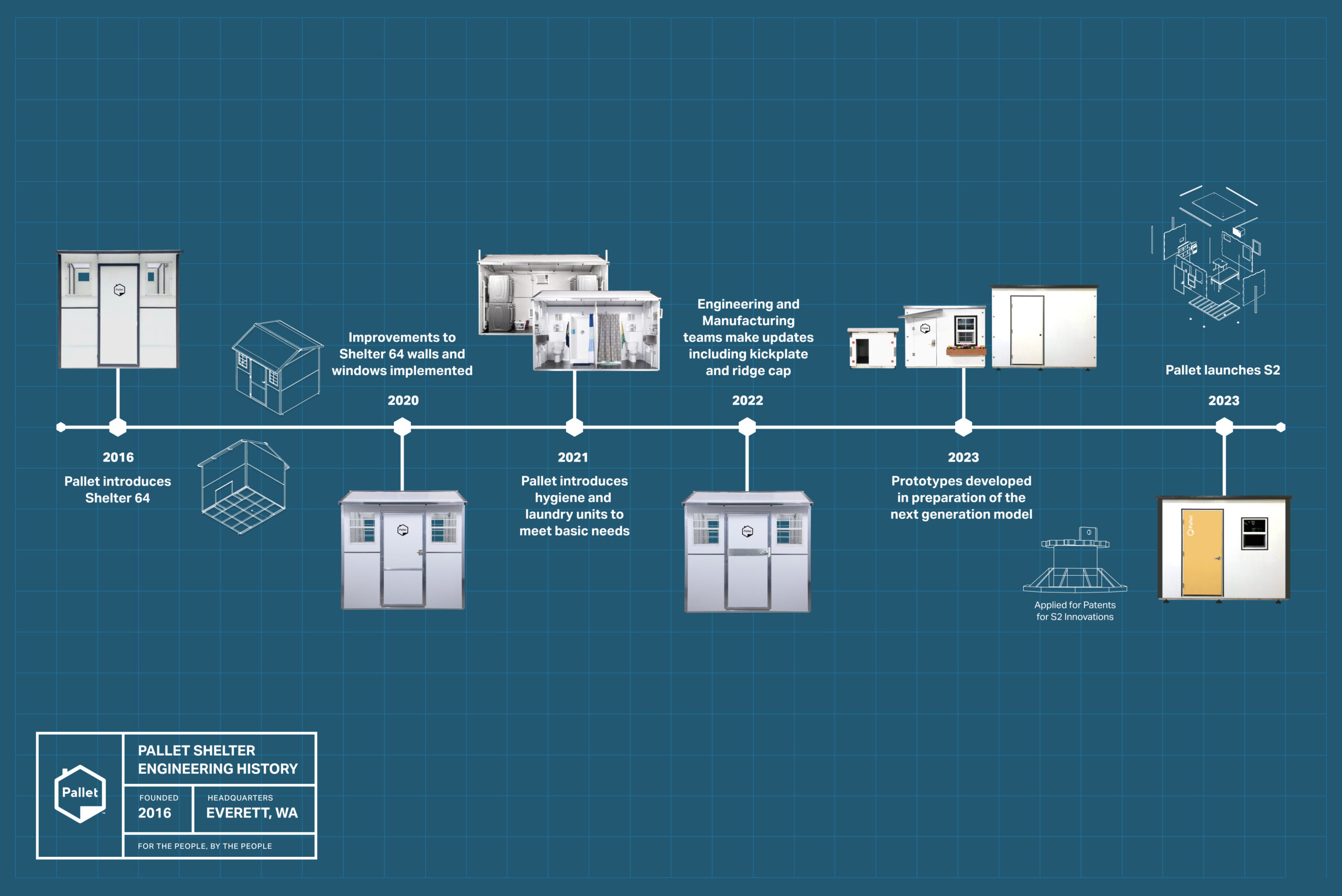

Look back at our top stories of the year: from product innovation to expanding our footprint and receiving dispatches from our villages around the country, these highlights capture what Pallet achieved in 2023.

As the year comes to a close, we’re looking back at the stories we’ve shared throughout 2023. With the most recent PIT count reflecting a 12% increase in homelessness in the U.S., the need for innovative solutions like Pallet continues to grow. Over this past year, our team has doubled down on lived experience-led product innovation with the development of our new S2 product line, all the while growing our capacity by adding over 300 additional shelters and laying the groundwork to expand our response into Canada.

Here’s a round-up of our top stories from this year.

1. Pallet Builds Its 100th Village

Just before Christmas in 2022, we crossed a milestone — building our 100th village. It’s located in Tulalip, WA which is just a short drive north of our headquarters. The location holds special meaning for some Pallet employees who previously experienced homelessness in the area and are now finding purpose in building transitional housing to help others in the community. The village is made up of twenty 64 sq. ft. shelters and one 100 sq. ft. shelter and was constructed in just two days by the Pallet deployment team. The Tulalip tribe manages the site and provides onsite services for community members. Residents moved into the 20 shelters early February 2023. [Keep Reading]

2. Jennifer & Alan: Closing the Loop Through Giving Back

The two first met each other a handful of years ago when they were living on the streets of the Tulalip Indian Reservation in Washington. Today, they’re coworkers at Pallet. Their witty humor makes them a dynamic duo dropping hilarious one-liners as they tell stories about their past. Indeed, they can have a crowd in stitches.

“I relate to many of the people here because we can laugh about things that most people would get appalled by,” Alan says in admiration of his co-workers, many of whom share similar lived experiences.

Jennifer agrees – they have witnessed the darker sides of life. But, she says, they’ve risen above them. “It’s like, you guys, we have overcome so much and we’re killing it now. We are rock stars,” she says, laughing.

She and Alan are proud to have surmounted substance use disorder and other challenges that are, truthfully, nothing to laugh at. Right now though, they’re excited to be working on Pallet shelters for a new village on the Tulalip Reservation where they were once unhoused themselves. [Keep Reading]

3. Introducing PathForward™

There is no one solution to end homelessness. Every municipality and every community have their own specific needs. While our Pallet villages coupled with wraparound supportive services are a successful model, we understand there are other strategies to address the homelessness crisis. Working closely with cities across the country, we realize communities want to find the right solutions and know our expertise and learnings from deploying over 100 shelter villages could help them drive change. So, we’ve launched PathForward™ homelessness advisory services.

Pallet’s PathForward provides support for cities to create customized solutions with defined goals and resources like funding roadmaps, implementation plans, policy research, capacity building, partnerships, project management and more. Our service uses data-backed strategies anchored by people with lived experience. Cities can work with Pallet in a variety of ways including long-term partnerships, special projects, and one-off advice. [Keep Reading]

4. Dignity as a Guiding Principle

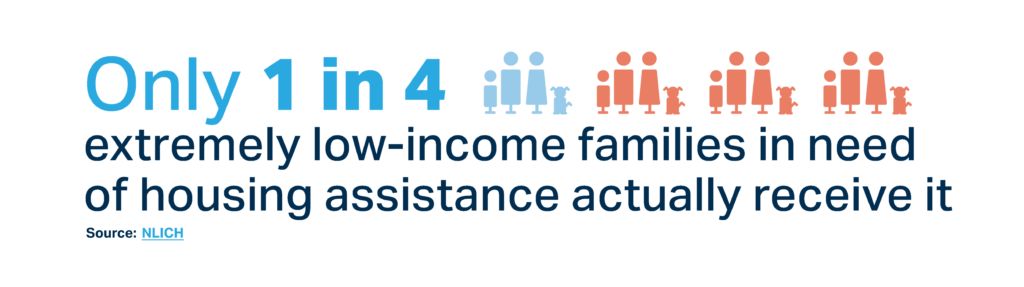

To help our unhoused neighbors transition out of homelessness and build a better future, providing shelter is one of many steps. A dignified living situation means reliable access to food and water, hygiene facilities, transportation, safety, supportive services, and more.

We created our Dignity Standards with these basic needs in mind. Guided by input from Pallet team members with lived experience, their purpose is to hold all stakeholders accountable, including ourselves, and always act in the best interest of the communities we serve. They also function as guidelines for the cities and service providers who operate our villages, intended to evolve and refine as we learn what works best. Because without dignity, who are we? [Keep Reading]

5. Rebuilding Her Life: Linda

In our Village Voices series, we shine a spotlight on residents living in Pallet shelter villages across the country and give them the chance to share their stories.

Linda Daniels was walking down the street with her bags looking for a place to sleep that night. An outreach worker happened to notice her and asked if she needed help. Within two weeks, she was a resident of the Rapid Shelter Columbia village.

A month in, Linda says the chance to have her own space to rest, to return to after a long day as a custodial worker at the University of South Carolina, and to collect her thoughts has been pivotal in being able to move forward.

“It means the world to me, because I got my own space, and I got my own place to where I can call mine right now,” she says. “I like being by myself a lot of times. So if I’m going through something, I can come in my room and think about what I’m going through and try to make things better. And I think this is a wonderful thing.” [Keep Reading]

6. Dave: Right Where I’m Supposed To Be

Early on, Dave had already made his own way in life. He started his manufacturing career with Boeing at age 20, got married, had three children, and bought a home for his family. After achieving all this and growing up in a large family in Everett with good relationships with his parents and siblings, it might come as a surprise to hear what was going through his mind at the hospital on May 12th, 2019.

“I was 100% resigned I was gonna die in my addiction,” he recalls. “But then that moment of clarity, that spiritual awakening, that epiphany, whatever you want to call it, hit me in there. I’m like, ‘this is not gonna be my legacy that I died with a f***ing needle in my arm sitting in the hospital. I’m gonna fight this,’ you know? And I did. And I appreciate every single day.” [Keep Reading]

7. Four Ways to Fund a Pallet Shelter Village

Pallet shelter villages serve as transitional spaces for people experiencing homelessness. They provide the dignity and security of private units within a community, along with a resource net of onsite social services, food, showers, laundry, and more to help people transition to more permanent solutions.

Several components to consider when building a village include identifying which Pallet shelters best suit the needs of the community, finding a site location, setting up infrastructure, and selecting a service provider. Funding is also crucial. Below are four sources that can be combined to fund the costs associated with creating a Pallet shelter village. [Keep Reading]

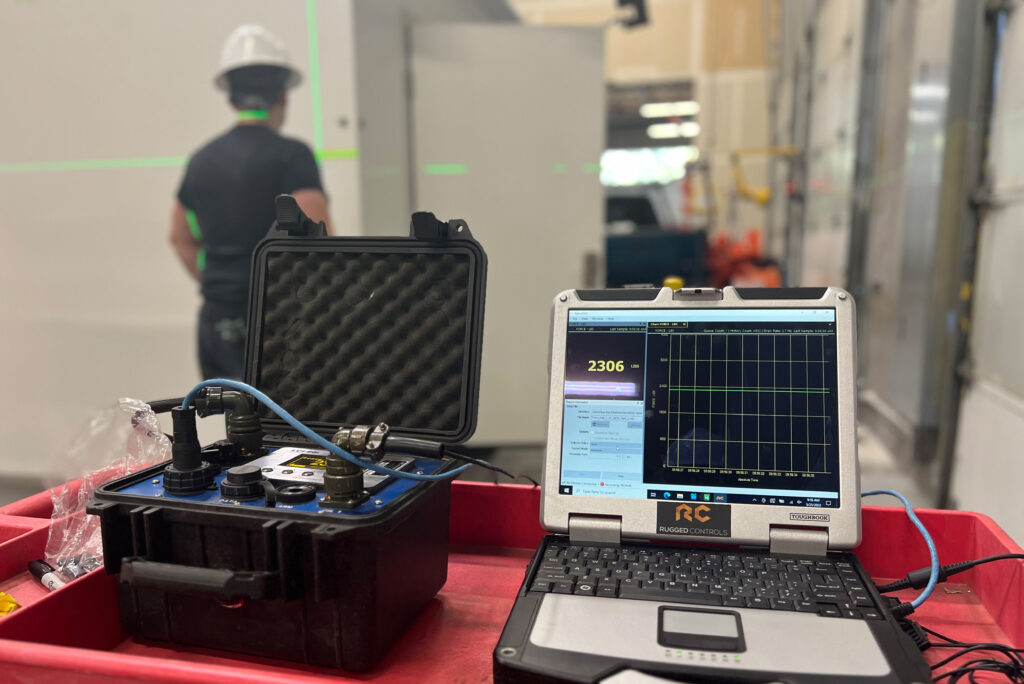

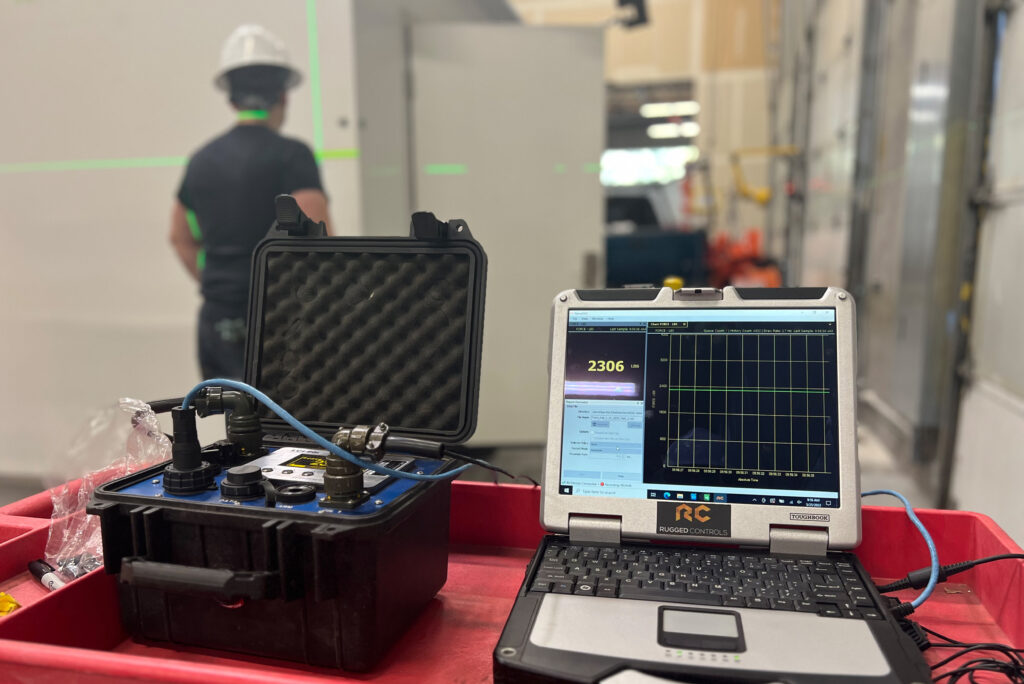

8. Proven Safety: Rigorously Testing and Certifying Our Shelters

With thousands of Pallet shelters across the country, we’re constantly gathering feedback on their design from customers. This information is crucial for our in-house engineering team. It allows them to understand what our shelters must withstand in the real world.

With that knowledge, they can design Pallet shelters to meet various demands, and rigorously test them onsite.

And yet, we don’t stop there. We also third-party certify our shelters to truly validate their designs.

All this is critical because our shelters often go into storm-prone and extreme weather zones. They must reliably protect the residents who live in them, all while remaining cost-effective.

Our new S2 shelters illustrate our deep commitment to R&D. Building on our legacy of intentional, quality engineering, they advance our mission to offer safe, dignified housing for displaced and vulnerable populations. [Keep Reading]

9. Rethinking Post-Disaster Housing Solutions

By now it’s a familiar sight: cities and towns ravaged by hurricanes, tornadoes, flooding, or wildfires; homes and living spaces decimated; and people ushered into stadiums, schools, or anywhere that has the capacity for those displaced. In 2022 alone, 3.3 million Americans were displaced by disasters—and one in six people never returned to their homes.

While mass congregate shelter is often the only viable option to aid survivors directly following a natural disaster, it is not a sustainable solution for the days, weeks, or months that follow. In the variable, unpredictable period when homes, rental housing, and other living facilities are being rebuilt, there is a distinct scarcity of interim shelter options that fit the diverse needs of displaced populations.

It’s time to take a closer look at why our current system of post-disaster housing isn’t sufficient, and to provide broader, more equitable options for people displaced by natural disasters. [Keep Reading]

10. Roxana: Power in Compassion

Most people would assume bringing a shelter village to life couldn’t be accomplished by a single person. Completing an undertaking of this scale is typically the culmination of a team of stakeholders overcoming various obstacles: identifying funding sources; finding an appropriate site; setting up necessary infrastructure like water and electricity; and rallying the community for support. Roxana Boroujerdi is unlike most people.

Located on the grounds of Everett’s Faith Lutheran Church, Faith Family Village comprises eight Pallet sleeping shelters and two hygiene units that will serve local families experiencing homelessness. The village will also offer supportive services that aim to create paths to employment, education, and permanent housing—alongside facilities and activities that create a safe and fun environment for children living onsite.

And even with her fair share of personal challenges, none of it would have come to fruition without Roxana. [Keep Reading]

After an emergency evacuation at a low-barrier permanent supportive housing site, Pallet was able to prevent resident displacement within 48 hours.

When thinking about emergency evacuations, it’s common that natural disasters like hurricanes, flooding, and wildfires first come to mind. But there are many other scenarios that can threaten the stability of a living situation and cause abrupt displacement, making the provision of emergency shelter solutions crucial in a moment’s notice.

Clare’s Place, a permanent supportive housing complex in Everett, WA, experienced exactly this kind of emergency in October.

When 48 of the 65 units in the building came back positive in tests for environmental contamination, all residents were forced to evacuate due to safety and health hazards. Clare’s Place is a low-barrier site that serves vulnerable community members including chronically homeless individuals, those diagnosed with mental illness, and people living with substance use disorder. Staff needed to identify an appropriate solution immediately to temporarily house the affected residents.

Everett Mayor Cassie Franklin promptly contacted Pallet’s Founder and CEO Amy King, looking to rapidly install shelter units to accommodate the residents evacuated from Clare’s Place. In order to serve the needs of those displaced, residents would need the ability to remain close to their possessions and case managers, so the units would ideally be built directly on the property.

Members of the Pallet Deployment team sprang into action. Working tirelessly overnight, they were assisted by Catholic Community Services (CCS, who operate Clare’s Place) and assembled 30 shelters in the parking lot. Snohomish County PUD also responded and supplied the site with power.

Within 48 hours of that initial call, shelters were deployed, assembled, and move-in ready as a safe and urgent solution to temporarily house residents of Clare’s Place. Because of Pallet’s stockpile of 64-square-foot sleeping shelters, the site was established with the urgency required for this emergency.

This unfolding of events speaks to the utility and efficacy of interim shelter as an emergency solution for displaced populations—particularly vulnerable communities that require hands-on supportive services. The capability to provide essential aid with urgency also points to the advantage of stockpiling this model of shelter. When residents living at the Clare’s Place site are able to move back into their apartments, the shelters will be stored as a supply for future emergencies in Everett.

To learn more about the instrumental role interim shelter can play in emergency situations, download our Post-Disaster Housing Continuum Infographic.

Through her success spearheading Everett’s Faith Family Village, Roxana is living proof that passion and perseverance can create lasting, positive change for the community.

Most people would assume bringing a shelter village to life couldn’t be accomplished by a single person. Completing an undertaking of this scale is typically the culmination of a team of stakeholders overcoming various obstacles: identifying funding sources; finding an appropriate site; setting up necessary infrastructure like water and electricity; and rallying the community for support. Roxana Boroujerdi is unlike most people.

Located on the grounds of Everett’s Faith Lutheran Church, Faith Family Village comprises eight Pallet sleeping shelters and two hygiene units that will serve local families experiencing homelessness. The village will also offer supportive services that aim to create paths to employment, education, and permanent housing—alongside facilities and activities that create a safe and fun environment for children living onsite.

And even with her fair share of personal challenges, none of it would have come to fruition without Roxana.

“I am 70, I have MS, and I was in a car accident and lost my knee,” she explains. “I have a lot of things that people might consider strikes against me. But with God, all things are possible.”

The idea for Faith Family Village was born in the throes of the pandemic while Roxana was running the church food bank. When people were no longer able to safely come inside and choose what they needed off the shelf, Faith Lutheran was forced to explore alternative options. The USDA was beginning to form partnerships with organizations to donate food to those in need, and someone from the Everett chapter of Volunteers of America (VOA) pointed them in Roxana’s direction.

“VOA told the USDA: ‘They should contact the crazy lady down at Faith Food Bank, she’d probably do it,’ she recalls. “So I told them to bring the big rig and we’ll work it out somehow. Little did I know that after a month, we had about 250 cars that came to pick up food—the line stretched [over half a mile] all the way to Value Village.”

After receiving help from a team of volunteers to distribute to the crowds, Roxana was able to connect with people one-on-one and ask why they came to the food bank. The amount of people that told her they were homeless or couldn’t afford to pay for their rent or food, including families living out of their cars, didn’t sit right with her. So she started researching.

Roxana discovered Pallet online and saw operational villages in nearby communities. She didn’t hesitate to contact the mayor of Burlington to see the Skagit First Step Center.

Mayor Sexton offered Roxana a tour, breakfast in the village’s community room (“and they gave me lunch because I stayed too long”), and even extended an invitation to stay overnight and experience sleeping in a shelter.

Learning about the structure and case management embedded in the village model prompted Roxana to take the idea of starting a new Pallet village at Faith Lutheran to fellow members of the congregation. While first met with opposition, she convinced the church council by taking them to a neighboring site in Edmonds and learning about the realities of hosting a shelter village community. The following council vote granted Roxana approval for building the village.

Then came the roadblocks.

Even with no experience navigating complex issues like land use laws and city zoning codes, Roxana tirelessly pushed through every obstacle in her path. First, she played an instrumental role in changing Everett city code to allow children to stay in Pallet shelters. Then she had to coordinate a series of tests to build on the church property—a survey for Indigenous artifacts, studies for noise and water runoff, and a slew of others. She had to obtain funding, which she procured through sources like Washington state senator project grants, sizeable donations from the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America (ELCA), human needs grants from the city of Everett, and donations from various community and congregation members. Local businesses like Rodland Toyota, who were already active supporters of the Faith Food Bank, also stepped up to donate supplies and interior furnishings for the shelters.

At first, Roxana was worried about pursuing funding streams. But she soon realized it was just another duty she could carry out herself to bring the village closer to groundbreaking.

“It’s a lot,” she says. “When I started, it was a lot of weight. But now that I feel like I have a community of donors that are also invested, that helps a whole lot. And now I’m not so shy in asking people: ‘Can you give me this or that?’”

One of the most significant obstacles Roxana encountered was raising community support. Many neighbors of Faith Lutheran expressed strong feelings against building a village on the church grounds, citing concerns of attracting criminal activity or encouraging an unsanctioned encampment nearby. One homeowner with property bordering the church attended a community meeting, adamant that the site would never be welcomed. Roxana wasn’t fazed.

“I gave my talk about how many kids are homeless,” she recounts. “And what happens to those kids’ futures, like not graduating or joining a gang or becoming the next generation of homeless people.”

The very next day, the neighbor called Roxana and offered $2,000 toward the village. Through his involvement in the village’s progress, he later donated all the materials for an upgraded perimeter fence surrounding the playground.

“I think God touched his heart and said, ‘No, it’s not right that these kids have to sleep outside,’” she says.

Faith Family Village will be assisted in operational duties by Interfaith Family Shelter, another site serving families experiencing homelessness in Snohomish County. Roxana says the village will offer services focusing on development for both parents and children: obtaining proper identification; enrollment in financial and rental certification programs; applications for housing vouchers; opportunities to volunteer at the food bank as a reference for future employment; after school tutoring; meals and chore sharing; and even family fun nights to foster a sense of community. They’ll also have interactive learning opportunities like cultivating a fruit and vegetable garden with the direction of local Master Gardeners.

In the face of so many challenges, Roxana’s sunny outlook and passion eclipses any notion of giving up in the face of adversity. And she has a message for anyone else who wants to provide a glimpse of hope for their unsheltered neighbors, even if it seems unattainable:

“I would say you should go for your dreams and help all the people that you can,” she says. “Because doing all that brings more joy to you than you can ever imagine. You can do it. You should try. And the thing I’m looking forward to now is spreading family villages everywhere.”

Living in the Rapid Shelter Columbia village, Jeffrey says he finds peace in the village’s safety, and the work program he’s involved in has made him more independent to embark on a new journey.

Before moving into Columbia’s shelter village, Jeffrey Hoover spent much of the past two years trying to find a safe place to rest, moving between a temporary congregate shelter and sleeping outside.

During a period staying behind the library, he learned from another unhoused neighbor about the village being built nearby. He connected with a social worker in the library and made it a priority to move in as soon as he could.

“I went the very next day, because he told me on a Sunday,” he says. “Monday morning, I was there, sharp.”

He says sleeping outside had a feeling of freedom, where he could see the stars and breathe the air. But he constantly felt worried about his safety—either being harmed by the elements or arrested for simply living his life in public. Staying in the village has made him feel more secure.

“I really love being here,” he says. “Because number one, it’s safe. Number two, when I was outside sleeping, I was always worrying about, ‘I gotta use the bathroom, where can I go?’”

With the help of his case worker, Jeffrey was hired to help run the village itself with custodial and watch duties. He feels like it’s helping him find structure and represents a link to finding permanent housing.

“It has made me sharper,” he says. “It has made me more dependable, independent. And because of the kind of person that I am, I know that this job one day will fade out because I'm looking for something even better and bigger. And I’ll find a place one day soon that I can call home.”

In the wake of natural disaster, an inclusive range of shelter and housing models is critical to meet the immediate needs of every displaced individual.

Following destructive events like hurricanes, flooding, and wildfires, large populations are suddenly displaced from their homes and forced to find refuge wherever it is available. People are often directed to arenas, schools, community centers, or other public buildings to find a safe place to stay—at least for the night.

What comes after this stage is filled with uncertainty. To fully understand the landscape of shelter and housing options in the wake of natural disaster, it’s important to consider that each community has diverse needs. Examining the scope of housing models and offering equitable aid to displaced populations lays the groundwork for sustainable recovery.

Read on to learn the language and timeline of the Post-Disaster Housing Continuum.

1. Post-Disaster Housing Continuum

The stages of shelter and housing presented on a timeline starting immediately following a destructive event. From emergency shelter models to the prospect of rebuilding permanent housing, the path of the continuum follows a displaced person’s housing journey after an emergency.

Each stage offers specific benefits and are either based on existing infrastructure or constructed for the specific purpose of sheltering disaster survivors.

2. Emergency Preparedness

Before a disaster occurs, communities can build resilience through comprehensive preparedness planning. This includes drafting plans for staffing emergency response teams, arranging amenities such as food provision and hygiene facilities, and stockpiling rapidly deployable emergency shelter options that can be used to accommodate both responders and displaced communities.

This stage is fundamental to create true resilience, equipping cities to recover more quickly and effectively in the wake of disaster.

3. Emergency Congregate Shelter

Perhaps the most familiar of post-disaster shelter models, this stage is occupied in the days (or even hours) following an event or evacuation order. Stadiums, gymnasiums, and other large public buildings are used to rapidly shelter large groups of displaced people under one roof.

While effective at providing a space for large populations, this stage tends to present high barriers even when outside conditions are unsafe. People with pets and those with specific prior offenses are not permitted to stay in congregate settings, and people with trauma from violence and sexual assault do not feel secure in large, open settings with others.

4. Interim (Recovery) Shelter

Individual interim shelters can be deployed and assembled rapidly, and communities can be tailored to the needs of specific groups (people with disabilities or medical needs, first responders, relief workers, etc.). This model is best suited for the weeks and months following a natural disaster when permanent housing is rebuilt.

Although a crucial part of the continuum due to its versatility and ability to centralize supportive services, this stage is often overlooked and underutilized in post-disaster scenarios.

5. Temporary Housing

Forms of this stage of the continuum can range from hotels to RVs and are intended to serve displaced populations in varied timelines: depending on the extent of the rebuild period and the economic status of the person affected, temporary housing could be occupied in the weeks or even months following a disaster.

While more viable than congregate shelter for most people, this model has the potential to turn into long-term housing that isn’t dignified. When existing infrastructure like hotels are converted to temporary housing, these spaces are costly and cannot be used for visitors or tourists, which can adversely affect the recovery of local economies.

6. Long-Term Recovery Shelter

This model leverages temporary, rapidly implementable structures built on private property to serve displaced individuals, families, or workforces rebuilding permanent housing.

Allowing people to stay on their own properties while rebuilding their homes is often the most ideal solution to keep residents within their communities and looking toward the future. Units that can be quickly built and later disassembled as needed is an effective way to foster a path to long-term recovery.

7. Permanent Housing

Providing attainable, stable permanent housing for every person is of course the ultimate goal following destructive events. However, this stage cannot be reached immediately, and even when permanent housing is rebuilt, opportunities are often stratified based on socioeconomic standing. There is no linear path for every individual to reach long-term stability.

The need for urgent and dignified shelter and housing models following natural disasters highlights the necessity of every stage of the continuum preceding permanent housing. A range of equitable options is crucial for long-term recovery—and resilient communities can only be built when these basic needs are met for every person.

To learn more about how to serve the diverse needs of disaster survivors, download our Post-Disaster Housing Continuum Infographic.

Michael’s time in Columbia’s Pallet village has given him the chance to focus on himself, his goals of becoming a business owner, and starting his new journey.

Michael served in the Army for 18 years and returned home to Columbia when a house fire claimed the lives of his mother, father, aunt, uncle, and two children. After this devastating loss, he had nowhere to call home. Insurance didn’t cover the tragedy he had sustained.

He temporarily bounced between different local homeless shelters, struggling with depression and turning to alcohol and substances. It was at one of the shelters where a fellow guest told him about the Pallet village being built nearby.

Michael says moving into the village has given him stability to rebuild his life.

“I’m finding myself,” he says. “I made some slips and falls, but I’m eager to get right back up. I'm mainly right now focused on how I can get back to where I need to be in life. Not where I was, but where I need to be.”

Working with his case manager, Michael is making steps to securing documents that were lost like an ID, birth certificate, and social security card to get approved for permanent housing. When he moves out of the village, he hopes to own and operate an auto shop—he already has experience in the field and an automotive service excellence (ASE) certificate.

After experiencing trauma, Michael still needs time to recover and stabilize. But he says living in the Pallet village and having his own shelter has given him peace of mind: he’s attending counseling for his depression and starting to see the potential for positive change ahead.

“You know, like I was telling a lot of people, life is like a noun,” he says. “You have to change people, faces, and things in order to get a better outlook on your life. And for my aspect of looking out, I want to see a brighter future for myself.”

He has hope that a new life is waiting for him once he transitions out of the village.

“In five years, I want to own my own home and have my own business,” Michael says. “With a new family. I see that promise.”

Learn more about the Rapid Shelter Columbia village by reading our case study.

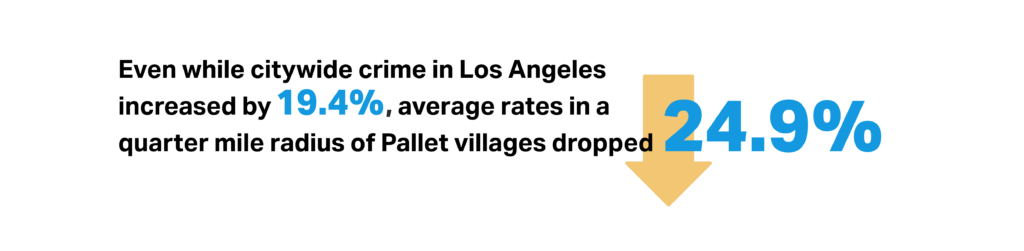

Understanding the link between equitable housing and public safety plays a key role in building safer, healthier, and more successful communities.

Housing is at the crux of many systems that compose a functional society, from healthcare to infrastructure. But even with decades of research proving the innate connection between stable, equitable housing options and public safety, conversations on the subject often overlook this significant relationship. On the contrary, many people believe the myth that some models of shelter and housing actually increase crime in surrounding areas.

Evidence shows these claims are false. When an inclusive range of shelter and housing options are offered to every community member, an abundance of positive effects can be observed: crimes committed by unsheltered populations out of desperation are significantly decreased; the cycle of incarceration and homelessness can be broken; and public costs are drastically reduced.

Recognizing the inherent link between housing and public safety and investing in a range of options that fit everyone’s needs has the power to make our communities safer, stronger, and more sustainable.

The Housing Inequity-Crime Connection

It is widely understood that crime does not exist in a vacuum: a number of environmental, social, and economic factors all contribute to the root causes of why people commit crimes. The fact that crime is more prevalent in economically disadvantaged neighborhoods and areas with higher rates of unsheltered homelessness illustrates how a lack of access to stable housing is at the core of the issue.

Higher crime rates have been associated with neighborhoods that experience poverty, residential segregation, and a lack of essential resources like good jobs, schools, and healthcare facilities. These disparities can be linked back to practices like redlining, which represent historical institutional oppression and racism that siloed equitable housing and services to more advantaged areas. When people living in these areas are denied access to attainable housing and resources, they are incentivized to commit crimes as a means of survival.

Poor land use practices, foreclosures, and vacancies also affect crime in these neighborhoods. One study found that in Pittsburgh, crime increased 19% within 250 feet of a foreclosed home once it became vacant, and continued to rise as it sat unoccupied. Examples like this could be avoided in the future by using similar lots for development of supportive housing or subsidized market rate housing.

It’s also crucial to consider that in cases of violent crimes, vulnerable populations are much more likely to be victims than suspects. Homeless people are targeted in hate crimes at double the rate of crimes based on religion, race, or disabilities. Unsheltered women specifically disproportionately experience violent assault like rape, causing lasting trauma and suffering that creates a new set of challenges in living in communal settings like congregate shelter.

Therefore, when people have stable places to live, they are less likely to commit or fall victim to crime, creating safer communities in the process.

Breaking the Cycle of Incarceration

The reality of laws criminalizing homelessness—or attaching serious charges to minor, nonviolent offenses like loitering, panhandling, and littering—is further proof that people are expected to have secure housing and not live their life in public. This is a serious challenge, considering a nationwide shortage of 7.3 million affordable rental units.

Statistics on the disparity of homeless individuals being arrested for low-level offenses is alarming. Although homeless communities represent less than 2% of the population in cities like Portland, Sacramento, and Los Angeles, they accounted for 50%, 42%, and 24% of total arrests from 2017-2020, respectively.

And once a person enters the prison system, regardless of their offense, it makes them significantly more vulnerable to living unsheltered: formerly incarcerated people are 10 times more likely to experience homelessness than the general public. This is especially concerning when one considers the fact that one in every three Americans has a criminal record.

Upon release from the system, formerly incarcerated people face numerous challenges in securing appropriate housing. The inability to make rent, stigmatization from landlords, and barring those with drug offenses from public housing are just a few common obstacles. By lowering these barriers, along with focusing on new inclusive housing and subsidized market rate developments, the prison-homelessness cycle can be effectively broken and improve public safety in the process.

Investing in Housing as Public Safety

The overall costs of policing, corrections, courts, and other reactive measures associated with public safety far outweigh national investment in housing and community development.

While the nearly $260 billion annual budget of the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) shows a concerted effort to fund more affordable housing and assistance programs, it pales in comparison to the price of operating the criminal legal system. When accounting for indirect economic effects of crime (property destruction and vandalism, utilization of healthcare and emergency services, forgone wages, etc.), the broader societal cost of the criminal legal system is estimated to equal $1.2 trillion.

Creating Safer, More Resilient Communities

There is undeniable proof that providing equitable, attainable housing is a guaranteed pathway to improving public safety. By incorporating this understanding into the development of new shelter and housing programs and acknowledging that the two concepts are inextricable from each other, we can make progress to end unsheltered homelessness and build safer, more successful communities as a result.

To learn more about the impacts of housing on public safety outcomes, download our Housing as Public Safety White Paper.

Even while cities face challenges in opening new shelter villages, there are various methods to overcome them and aid vulnerable populations experiencing homelessness.

Many cities that aim to address their unsheltered homelessness crises see the benefits of interim shelter villages but face barriers in opening new sites. After encountering a wide variety of obstacles in our work with cities across the country, we can share our successes navigating these difficulties as a blueprint for any municipality aiming to provide equitable shelter for their vulnerable communities.

Whether it’s community opposition, trouble accessing funding, finding proper potential sites, or issues concerning infrastructure and zoning ordinances, our Community Development team is well-versed in finding tailored solutions for each city’s unique challenges.

We have found successful techniques to overcome many different barriers, but the following three arise the most frequently. Read on to learn how a diverse set of cities have succeeded in opening their own Pallet village despite adverse conditions.

Barrier 1: Accessing and Obtaining Funding

One of the first concerns that arises when considering building a Pallet shelter village is a simple question: how will we fund it?

Navigating funding options presents its own set of challenges, but we have seen villages built across the country utilizing a spectrum of different sources, from federal assistance programs to private donations. Some examples include:

- Federal Level Funding Sources

- American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA)

- Community Development Block Grants (CDBG)

- Home Investment Partnership Program (HOME)

- Local Municipality and State Government Funding

- State Funding

- County Auditor Funds

- City Funds

- Grants and Contributions from Private Sources

- Regional Housing Trusts

- Donations from private foundations, philanthropic organizations, corporations, and local donors

- Homeless Housing, Assistance, and Prevention Grant (HHAP)

While all of these are viable funding sources, we have also seen cities successfully combine funding from each level, and in the process, aid their unsheltered populations with appropriate urgency.

Barrier 2: Zoning and Land Use Challenges

Finding suitable and affordable land to build an interim shelter village can be a daunting task without assistance. But by working with local government boards, involving the community, and approaching land use challenges creatively, we have helped bring many Pallet shelter villages to life.

The following illustrate a few examples of how cities have overcome this specific barrier:

- Working with Legislature

One city sidestepped legal barriers by passing a city council vote to exempt a proposed site from specific building and zoning codes—while ensuring safety by working with the fire marshal during site development.

- Collaboration and Community Education

We witnessed a success story that involved creating an open forum composed of shelter organizations, community groups, landowners, and neighbors. By holding an open dialogue between all stakeholders in public meetings and coming to a solution that worked for everyone, the city was able to integrate a Pallet village into an existing residential neighborhood.

- Identifying Emergency Laws

Being aware of emergency land use laws has helped shelter communities develop over a significantly quicker timeline: by classifying unsheltered homelessness as the crisis that it is, we have seen cities provide essential shelter and supportive services with urgency.

- Creative Land Use

Creatively recategorizing property types has been another avenue of overcoming this particular barrier. One city even implemented a creative land classification to bring shelter and warmth to their unsheltered community right before the harsh cold of winter arrived.

While these solutions to these problems may not be self-evident, our Community Development team is adept and experienced in surmounting land use and zoning hurdles.

Barrier 3: Gaining Community Support

Community opposition often stands in the way of successfully building new shelter villages. We have found that by establishing an open line of communication between local governments and the public and providing education about the benefits of interim shelter, staunch opposition can often be transformed into outspoken support.

Some methods that have produced positive outcomes by engaging the community include:

- Alleviate concerns through education and disproving myths.

Common concerns surrounding new shelter villages are often based on the fear that these developments will increase crime and decrease neighboring property values. Providing facts to prove the opposite is true—such as data showing crime rates decreasing in areas surrounding new sites—can often spur a collective change of opinion.

- Host a village open house.

Demonstrating the inherent dignity and safety of Pallet villages has proven to be a boon to gaining community support: we have seen multiple cities host open houses where city leaders and heads of local organizations will stay in a shelter overnight to exhibit its potential in helping vulnerable people reintegrate and transition to permanent housing.

- Include the community in the decision-making process.

Ideas like creating a website to keep the public updated on crucial information and resources regarding a potential village or hosting community meetings that allow neighbors to voice their opinion has helped support efforts to develop new sites in various locations.

Interim shelter plays a crucial role in providing people with a stepping stone toward permanent housing, and examples like Pallet villages with onsite supportive services meet diverse needs of different displaced populations. And even while the model is proven to be an important part of resilient communities, city leaders are often impeded in the process.

Learn more about how Pallet’s Community Development team can help you maneuver barriers regarding funding, zoning and land use, and community opposition by reading our case studies.

Thorough and rigorous testing means our shelters can perform in varying extreme weather conditions—whether it’s rain, snow, wind or heat, we know that residents of Pallet villages across the country are safe.

With thousands of Pallet shelters across the country, we’re constantly gathering feedback on their design from customers. This information is crucial for our in-house engineering team. It allows them to understand what our shelters must withstand in the real world.

With that knowledge, they can design Pallet shelters to meet various demands, and rigorously test them onsite.

And yet, we don’t stop there. We also third-party certify our shelters to truly validate their designs.

All this is critical because our shelters often go into storm-prone and extreme weather zones. They must reliably protect the residents who live in them, all while remaining cost-effective.

Our new S2 shelters illustrate our deep commitment to R&D. Building on our legacy of intentional, quality engineering, they advance our mission to offer safe, dignified housing for displaced and vulnerable populations.

Pallet S2: The next evolution

The S2 line is the next chapter in Pallet shelters, shaped and guided by those with lived experience. Designed to be stronger, easier to assemble, and even more comfortable, our S2 products reflect feedback from residents of Pallet villages, service providers who operate the villages, and our own lived experience workforce.

This crucial input—gathered from all across the country—helped our engineers redesign interior features and simplify the structure, which in turn reduced costs.

Yet, their biggest focus was fortifying the S2s against intense weather. In doing so, they made the S2 shelter a reliable and universal solution for safe and comfortable living—virtually anywhere.

Engineered for the Real World

Whether it’s tornado-force winds, intense snow storms or severe heat, Pallet shelters must be engineered to handle it all. Pallet villages exist in places that experience severe weather events and our shelters must provide protection in these challenging environments.

“In south Florida, you have 140 mile-an-hour winds. In Maine, we have to withstand 40 lb. of snow per square foot,” says Pallet Engineer Trevor Russell. “We have villages in the deserts of California and the mountain towns of Denver.”

Water is a tough culprit for any structure. To shield against it, the engineers designed the S2 wall panels without rivets, and improved the subframe’s flashing and tension rods, eliminating even the smallest gaps where water might find its way in.

To maintain the S2’s ability to bear maximum snow loads while simplifying the design of its roof, our engineers updated from a two-piece design to a mono-pitch roof.

The new roof and subframe work together to create a unique tensioning and compression system. This increases the wind speeds the shelters can endure. The patent-pending design allows them to transfer sheer force through their sidewalls, providing incredible strength so they hold up in tornado-like wind.

“Our goal was to create shelters that work in the entirety of the U.S. and Canada,” Trevor says. Pallet shelters meet structural codes in nearly every state.

Rigorously tested onsite

Once Trevor and his team had created a prototype of the S2, they devised onsite tests to challenge it.

To test its waterproofness, they blasted it with a giant hose—inflicting an intense amount of direct water pressure all across the unit.

To simulate snow loading, they heaved sandbags onto its roof and measured the deflection of the panel.

And when it came to testing whether the shelter held together in the fiercest of winds, the team attached a winch and pulley system to the wall and plates to the shelter and pulled till they reached nearly 6000 lbs–nearly taking out a Pallet warehouse shop wall in the process

“The idea was to put sheer force along the walls and then see what fails,” Trevor says. “We started getting worried that the wall of the shop was going to fail.”

The S2 held up, withstanding the force of 155 mile-per-hour winds.

Third-party certified

Through this testing phase, the Pallet engineering team partners with a third-party structural engineering firm. These outside engineers are onsite to validate the tests and witness first-hand how the structures perform.

“We work with the firm to make sure our test design meets all the specs. Then, they review our testing data and make sure we pass whatever specifications we need to,” Trevor says.

Once a shelter design passes all tests, the engineering firm awards it a PE stamp of approval, which is an officially recognized certification of performance.

Inspired designs