On a recent advocacy trip to Washington D.C., the Pallet team met with policymakers to discuss the core of our mission to end the homelessness crisis.

Pallet Team Dispatch from D.C.

Last week, the Pallet team traveled to Washington, D.C. to talk about our mission and how we can help tackle challenges impacting communities across the country. We met with policymakers including congressional staff, members of the Trump administration like Housing and Urban Development Secretary Scott Turner, and local officials at the National League of Cities Conference where our CEO Amy King gave an address.

It was an exciting opportunity to discuss issues ranging from strengthening disaster response to expanding access to transitional shelter for individuals experiencing homelessness. Communities across America are facing urgent challenges, and the Pallet team is grateful for the opportunity to work alongside leaders who are prioritizing safe, dignified shelter that supports recovery and stability. One message was clear in every conversation we had: housing alone isn’t the solution—community is.

At Pallet, we are committed to providing innovative shelter solutions that help people find safety, community, and a path forward. But solving homelessness requires more than just shelter—it requires connection. For too long, we’ve treated homelessness as just a housing problem. But four walls and a roof don’t solve the deeper issues that lead people into homelessness in the first place, or more importantly, the traumas that come from living even a single night unsheltered. What’s missing? Community.

When people experience homelessness, they’re often uprooted from their communities. They lose their support systems, and without that foundation, it’s nearly impossible to regain stability. Shelters can provide temporary relief, but without a built-in network of care, many people end up right back where they started. This is something our team heard again and again last week. Local leaders are searching for ways to create not just shelter, but stability.

The crisis of homelessness has often felt insurmountable. But there is good news. Communities already have the power to create change, and many are actively working to do so. Grassroots efforts, local organizations, and everyday people are stepping up to provide food, shelter, and belonging. We see it in faith groups opening their doors, in neighbors organizing mutual aid, and in cities choosing to invest in real solutions rather than quick fixes. Pallet is proud to help support these efforts.

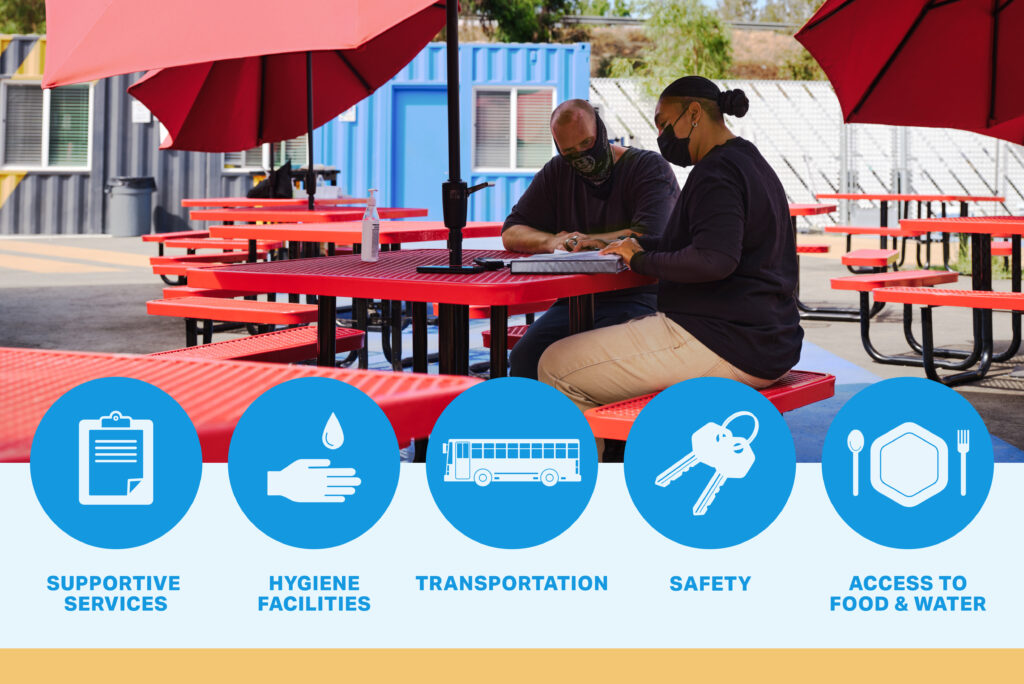

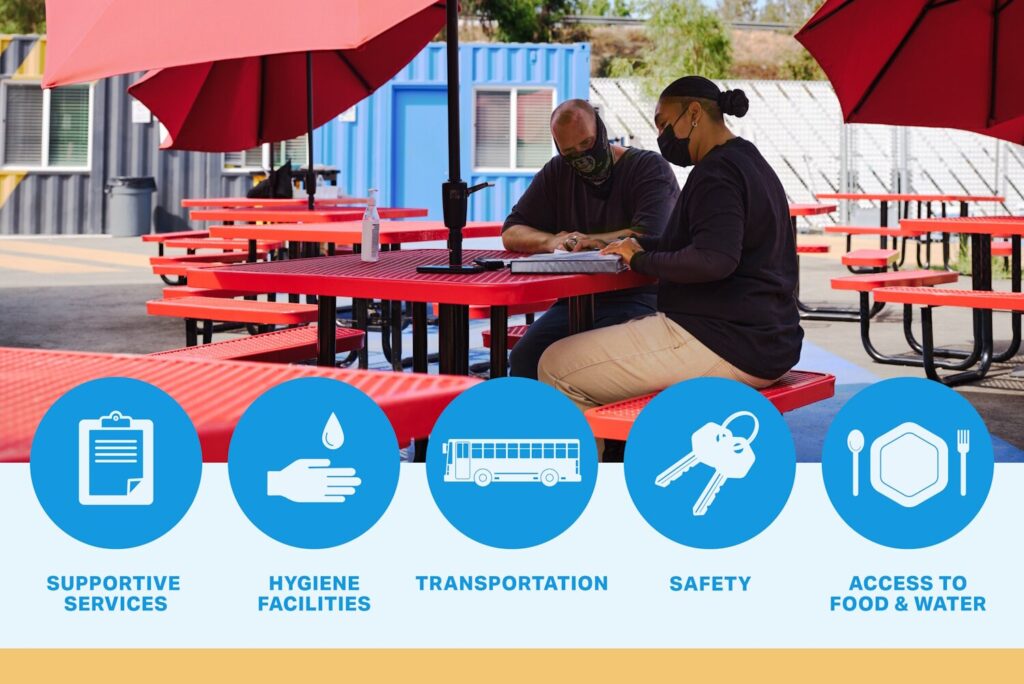

At Pallet, we’ve seen firsthand how community-driven solutions make a difference. We are working with communities across the country to help establish emergency solutions that provide more than shelter – they provide necessary connection to essential services within a rehabilitative community setting. They allow people to stay with family, keep their pets, and access the resources they need to heal. When we build with community in mind, we create spaces where people can truly start again while equipping them with the independence to choose what they know will work for them.

During our conversations in Washington, we sought to educate policymakers about the benefits and opportunities Pallet’s model can support. We also took time to listen to the challenges they are confronting in their communities. Our team believes that by working together, we can make real change while prioritizing the needs and benefit of the American public.

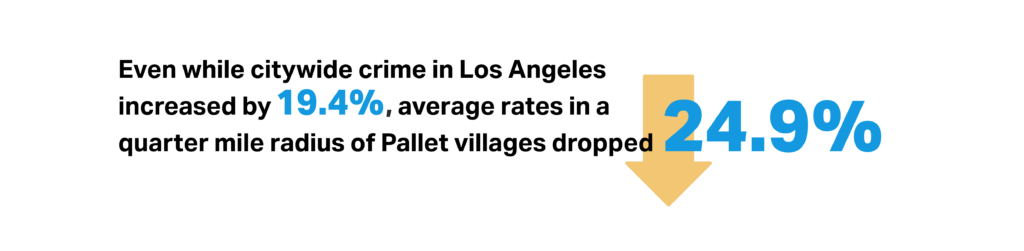

We have the experience to ensure our solutions work in the real world. As policymakers work to combat rising homelessness and limited budgets, new and innovative solutions are needed. Pallet products are cost-effective, scalable, designed and manufactured in the U.S., and built for real impact. Pallet villages demonstrate that it is possible to provide immediate shelter that honors individual dignity and self-sufficiency while also investing in long-term recovery, resiliency, and sustainable, lasting community building.

To read Pallet CEO Amy King’s Op-Ed on what it takes to effectively end the homelessness crisis, click here.

As displacement reaches unprecedented levels, it’s time to shift from the status quo and invest in models like Pallet that are intentionally designed to address this crisis.

With the number of people displaced by natural disasters and homelessness growing year after year, this crisis has reached historic levels. A 2022 survey found that 3 million Americans were forced from their homes due to natural disasters over the course of a year, while HUD’s 2024 PIT Count shows an unprecedented 18% increase in domestic homelessness.

Current solutions are not adequate to address the diverse and evolving needs of these populations, whether displacement is caused by climate-related events, the lack of affordable housing supply, or myriad other reasons. It’s time to reexamine shelter options that offer efficiency, long-term cost savings, and intentional design to solve for the crisis at hand.

Intentional Design, Proven Effectiveness

The disadvantages associated with conventional shelter models, from mass congregate settings to temporarily utilizing hotels and apartment buildings, demand alternative approaches that can provide a sense of stability and dignity. Many of these inadequacies stem from the fact that they are not designed to meet the varied needs of displaced residents following an emergency.

Traditional congregate shelter offers the ability to rapidly shelter a large amount of people under one roof, but its efficacy is limited to a short period of time following a natural disaster due to a lack of privacy and anxieties surrounding health and public safety. This approach also has demonstrated shortcomings for individuals experiencing homelessness. In some situations, unsheltered people are reluctant to accept a bed in a nightly congregate shelter due to safety concerns—particularly those who have lived through trauma such as domestic violence or discrimination.

In recent years following the COVID-19 pandemic, communities have turned to non-congregate models. Often, this means repurposing hotels and apartment buildings to use as temporary emergency shelter. Studies have shown that these models often lead to higher acceptance rates and satisfaction from people who have stayed at congregate shelters, but over time, operating costs can become exorbitant. For example, after the devastating Lahaina wildfires on Maui in August 2023, it was found that over 2,500 displaced Hawaiians were put up in hotels that cost taxpayers up to $1,175 per night.

Pallet’s innovative panelized shelter design and site model solves these issues. Not only do we use a trauma-informed approach to create our shelters, but sites are operated with the goal of providing residents with the onsite supportive services needed to build—or rebuild—their futures. Families, couples, and individuals with pets are allowed to stay together in the privacy of their own personal unit. And because Pallet shelters are durable and reusable for 15+ years, they offer communities long-term cost savings and can be easily disassembled and redeployed as needed.

Versatility and Rapid-Response Capabilities

In densely populated areas with ongoing unsheltered homelessness crises, unexpected emergencies (like an extreme weather event) can compound preexisting housing shortages. Those experiencing homelessness could be pushed out of hotels or other temporary stays to accommodate people who have lost their homes. In these situations, such as the prolonged cleanup of the Los Angeles wildfires due to health and safety concerns, a Pallet site could be rapidly developed to accommodate displaced residents while eliminating the need to force underserved populations out of shelter and onto the streets.

When compared to the noted high price and infrastructure needs of FEMA trailers, not to mention their steep depreciation and inability to efficiently store them after use, Pallet is an economical and adaptable choice for non-congregate emergency shelter. With minimal site preparation requirements and low ongoing operational costs, all that’s needed to set up a Pallet shelter site is a flat plot of land and standard utility hookups for electricity and communal hygiene facilities.

Improving Solutions to the Displacement Crisis

We know that current offerings for emergency shelter are limited and insufficient. It’s time to invest in innovative models like Pallet, which can be easily adapted to the various and evolving needs of communities in crisis.

By more effectively allocating funding and resources to non-congregate shelter models, communities can offer the stability needed for displaced residents to transition to permanent housing—all while building resilience and improving responsiveness to future emergencies.

The human displacement crisis in the U.S. has never been more severe. Heading into 2025, the Pallet team is more driven than ever to create positive, lasting change.

As we plan for the year ahead, the Pallet team is motivated to continue our mission to provide shelter for displaced populations. And with recent data showing escalating numbers of people impacted by this crisis, we’re aware that the need for safe, stable spaces is more critical now than ever.

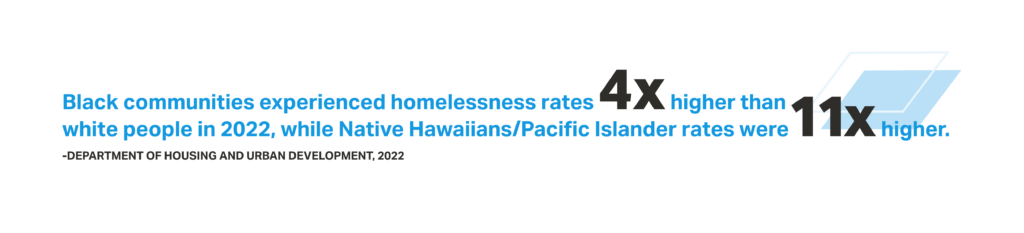

The Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) 2024 Point-in-Time Count reported that 770,000 people across the U.S. experienced homelessness on a single night in January. Not only does this represent a troubling 18% rise in homelessness from the previous year’s statistics, but we know that the difficulties associated with collecting this data means this number is likely much higher in reality.

In addition to the historic numbers of people experiencing domestic homelessness, a swath of devastating climate-related events also contributed to an immense rise of people displaced by natural disasters across the country. According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, from 1980 up to 2024, the average number of disasters per year causing $1 billion of damage or more was nine; 27 such events occurred last year. Hurricane Helene, which struck Florida’s Big Bend region back in September, caused $79.6 billion in damage and 219 recorded deaths alone.

Until every person has a place to call home, we will continue our fight in addressing the human displacement crisis. This scope of work is broad, but there are several specific strategies Pallet is implementing in 2025 on federal, state, and local levels.

Shifts in the Federal Administration

As President Trump takes office for a second term, changes in leadership and priorities for the country follow closely behind. Newly appointed officials and leaders will affect national strategies to address homelessness as well as disaster preparedness and response.

This means the Pallet Government Affairs team will be visiting DC in the next several weeks to meet with elected officials and their staff, ready to share Pallet’s vision, product offerings, and plans to effectively integrate our model into federal strategies.

We are looking forward to the official confirmations of the new heads of HUD and FEMA, which will allow us to align Pallet with the new direction of these crucial departments at the core of our work. Collaborating with these policymakers is key in establishing an environment that fosters positive change in people’s lives rather than implementing punitive, inequitable measures that do nothing but exacerbate this crisis.

Addressing Displacement in States and Counties

While the new federal administration will be influential in creating national policies, each U.S. state faces its unique challenges in providing appropriate shelter and housing for their displaced residents.

In our experience creating shelter sites across the country, we have learned that solving these issues requires tailored strategies that not only include shelter provision but also supportive services and many other considerations that meet the specific needs of impacted populations.

We utilized this expertise and insight to create a Five-Year Strategic Plan to End Homelessness for Savannah and Chatham County Interagency Council on Homelessness. The plan, formulated through meetings with key stakeholders and collecting relevant data, includes a comprehensive strategy to reach functional zero homelessness for the broader Savannah community. We will use this approach as a framework for designing effective, actionable, and thorough solutions to state and countywide displacement going forward.

On the front of climate-related events, this year we are placing a focus on demonstrating how non-congregate emergency shelter can play a pivotal role in strengthening resilience for disaster-prone states. We have already proven Pallet’s efficacy in responding to emergencies after building a shelter site for Floridians impacted by Hurricane Helene just days after the storm had passed. In the coming year, we are eager to expand this capacity for communities at risk of experiencing events like hurricanes, fires, and flooding—and increase access to rapidly deployable shelter when they need it most.

Making an Impact in Our Community

Pallet would be nothing without our people. Everything starts at our HQ in Washington State: before we can help displaced populations across the country, we are committed to providing stability and growth opportunities for our team members.

We created our Purpose-Led Workforce Model to advance this mission. A pivotal part of this model is Pallet’s Career Launch PAD (Program for Apprenticeship Development), which entails working on the manufacturing floor at HQ while participating in a paid pre-apprenticeship program focused on developing critical skills needed for a career in the trades.

We are looking forward to celebrating the graduation of our Career Launch PAD’s first cohort in 2025. After our team members complete the program, they will have the chance to pursue a rewarding career in the trades and become the skilled workforce of the future, creating more available space at Pallet for our next class in the process.

The displacement crisis in the U.S. has never been more dire. Through targeted efforts to address it on federal, state, and local levels, Pallet is driven to be part of the solution. Together, we have the chance to create lasting change in the coming year and ensure no one goes unsheltered.

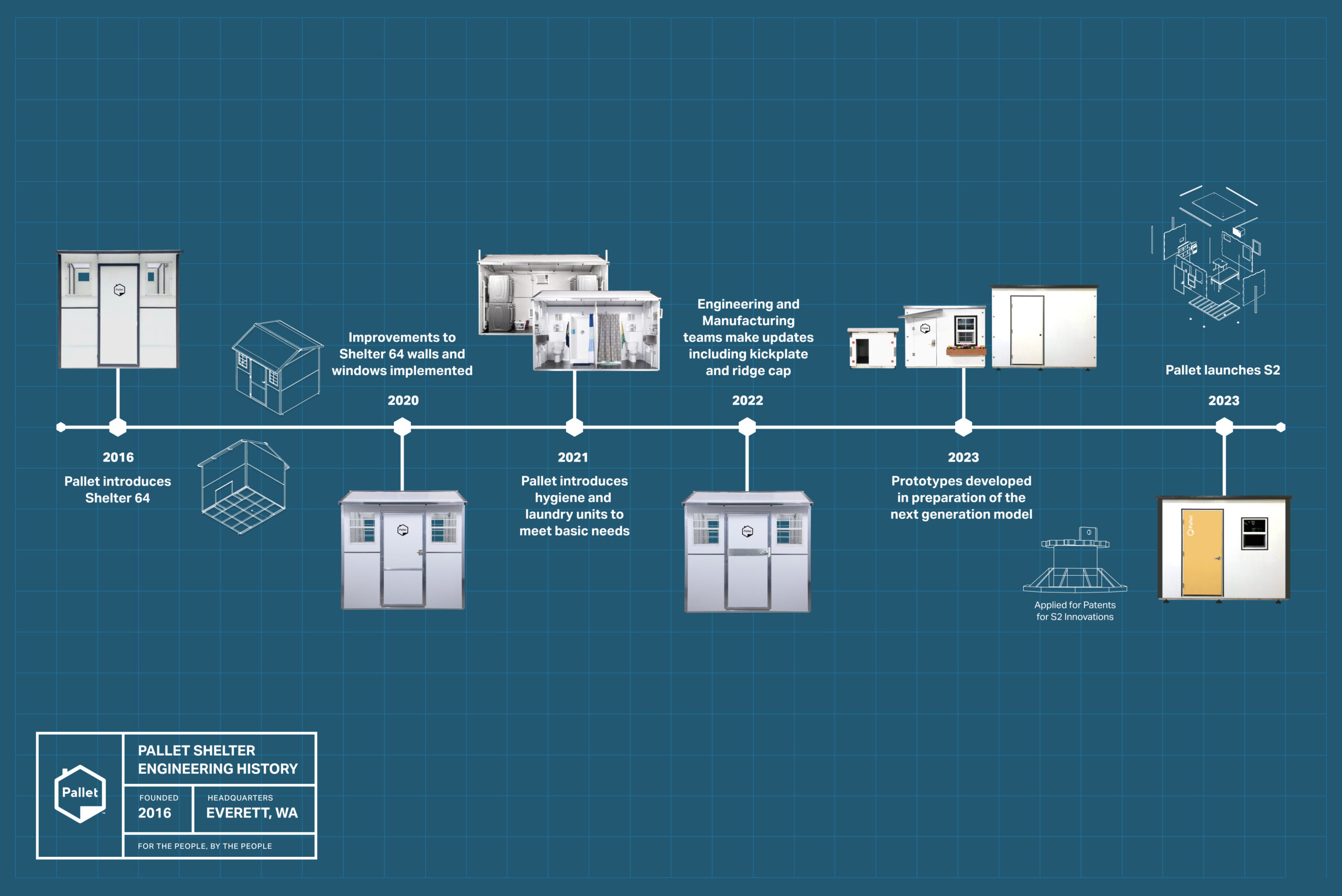

From launching a new product to expanding our footprint and creating our new workforce model, it was an eventful year at Pallet. Read on for our top stories of 2024.

As we look back on 2024, we are both proud of our advancements in providing safe, secure spaces for unsheltered populations and motivated to keep pushing forward. Even as we passed 5,000 shelters built in North America, expanded our reach into Canada, and released a new innovative product line to offer faster deployment and comfort for residents, the human displacement crisis persists—encouraging the Pallet team to continue working tirelessly until everyone has a stable place to call home.

Here's a round-up of our top stories from this year.

1. Pallet Hits the Road in California

Kicking off the year, the Pallet team embarked on a roadshow through California to showcase our new S2 product line and meet people working on the ground in their communities to solve their local displacement crises. We stopped in 11 different cities from Sacramento all the way to Los Angeles, displaying our S2 units and demonstrating the positive impact Pallet has made for unhoused communities across North America. [Keep Reading]

2. Launching Our S2 Shelter Line

Featuring an innovative panel connection system enabling even faster deployment, improved safety features, and increased comfort for residents, our S2 line is the next evolution of our in-house engineered and manufactured shelter products. Every decision we made in developing these new products was informed by input from residents living in Pallet shelters across the country and our own lived experience workforce. [Keep Reading]

3. Pallet's First Canadian Site Opens in Kelowna

Offering 60 individual shelter units for people experiencing homelessness in Kelowna, BC, STEP Place is Pallet’s first community installed in Canada. The City of Kelowna partnered with the Province of British Columbia and BC Housing to provide safe, secure spaces for people to stabilize and access onsite services provided by John Howard Society of Okanagan and Kootenay.

“We recognize the immediate need to bring unhoused people in Kelowna indoors and provide them the care they need,” said Ravi Kahlon, Minister of Housing. “Through this housing, people experiencing homelessness can be supported as they stabilize and move forward with their lives.” [Keep Reading]

4. Denver Opens First Village of S2 Shelters

Just in time for the New Year and part of Mayor Johnston’s plan to house 1,000 unhoused Denver residents by 2025, the opening of the city’s first micro-community also marked the first site comprising Pallet’s S2 Sleeper shelters.

“This is such a symbol of what we wanted to create,” said Cole Chandler, the mayor’s homeless czar. “It wasn't just about getting people indoors, but it's about bringing people back to life and helping people thrive. And you see that in this space.” [Keep Reading]

5. Introducing Our Purpose-Led Workforce Model

From the very beginning of Pallet, we have placed our team members at the core of our mission to give people a fair chance at employment. The majority of our staff have lived experience of homelessness, incarceration, recovery from substance use disorder, or involvement in the criminal legal system. With our Purpose-Led Workforce Model, we are taking the next step in helping our team grow and advance their careers. [Keep Reading]

6. Public-Private Collaboration in Santa Fe

Working together, the City of Santa Fe and Christ Lutheran Church opened the state’s first micro-community of its kind to provide shelter and supportive services for unhoused New Mexicans.

“It takes a community working together to really solve the challenge of homelessness, and that is our aim: to have zero homelessness in Santa Fe,” said Mayor Alan Webber. “We will keep working to make sure the people who are homeless in Santa Fe are housed, safe, secure, with respect, dignity, and with services.” [Keep Reading]

7. Tonya: "I feel like I'm doing something worthwhile"

Tonya knows Everett like the back of her hand. She spent most of her childhood on the north side of town but has lived in various neighborhoods throughout her life. So it seems fitting that now, after a decade of living on the streets of her hometown, she’s found a new path at Pallet and already moved into a place of her own mere steps away from HQ.

As one of the first participants in Pallet’s Career Launch PAD (Program for Apprenticeship Development), Tonya and her classmates are starting on the path to building independence and a brighter future for themselves. [Keep Reading]

8. Pallet Provides Shelter in Response to Hurricanes Helene and Milton

In rapid response to the disasters sustained in Florida following two major hurricanes, the Pallet deployment team jumped into action to build 50 shelters to help people get displaced by Helene and Milton get inside to safety.

By working closely with Pasco County administrators, county commissioners, facilities departments, and Catholic Charities, we were able to deploy and assemble the shelters mere days after the storms passed. [Keep Reading]

9. Connecting Pallet Team Members with Housing

At Pallet, our people are our purpose. Giving people a fair chance at stable employment and creating a supportive environment that fosters wellness and growth for all our team members is a crucial part of our mission.

A key part of this is ensuring that everyone on our team has all the tools and resources they need to succeed. In our work building shelter communities for displaced populations across North America, we know firsthand how having a safe, stable place to live is not only a basic human right—it is also the foundation for maintaining health, helping those with substance use disorder on their recovery journeys, and healing trauma.

That’s why we are proud to have become a Community Partner with Housing Connector, an organization that helps find housing for marginalized individuals and families. In our first year of the partnership, Housing Connector has been instrumental in finding housing for 4 Pallet team members by removing barriers and locating available properties. [Keep Reading]

By partnering with Housing Connector, we are helping our team members establish stability and independence.

At Pallet, our people are our purpose. Giving people a fair chance at stable employment and creating a supportive environment that fosters wellness and growth for all our team members is a crucial part of our mission.

A key part of this is ensuring that everyone on our team has all the tools and resources they need to succeed. In our work building shelter communities for displaced populations across North America, we know firsthand how having a safe, stable place to live is not only a basic human right—it is also the foundation for maintaining health, helping those with substance use disorder on their recovery journeys, and healing trauma.

That’s why we are proud to have become a Community Partner with Housing Connector, an organization that helps find housing for marginalized individuals and families. In our first year of the partnership, Housing Connector has been instrumental in finding housing for 4 Pallet team members by removing barriers and locating available properties.

Increasing Housing Attainability

Beyond the fact that there is an extreme shortage of affordable housing units nationwide, the scarce remaining options are often unattainable for applicants that have histories of incarceration, substance use, or bad credit. These widespread discriminatory practices can prevent vulnerable people from finding permanent housing, even if the applicant has proven progress in employment stability and/or sobriety.

Through their Zillow-powered platform, Housing Connector displays a list of eligible units in the area available through their Property Partners. From there, applicants are provided a letter of support that can be submitted to the property manager. Once approved, residents have access to an ecosystem of support including legal resources, conflict resolution, financial assistance, and two years of personal case management to establish housing stability.

Pallet Peer Support

As we hire new members onto our team to build their futures, we conduct screenings to assess our employees’ satisfaction with their housing status among various other wellness evaluations. This process helped establish our partnership with Housing Connector.

Sarah, our Customer Service Lead, serves as an essential onsite consultant for Pallet team members who want to access supportive services. When she moved into her current apartment, she personally used Housing Connector for an added layer of financial security and peace of mind.

This positive experience motivated her to pursue Housing Connector as a Pallet resource that employees could access if they were struggling to secure or maintain housing. She says this support can be crucial for people who are struggling to get approved for traditional housing based on their background or experience.

“Typically they vouch for our people, meaning those people who have criminal backgrounds, bad credit, evictions, debt, and who normally can't get approved,” she says. “Without that letter of support, most of them probably wouldn’t even be able to get into an apartment. It’s like a Willy Wonka Golden Ticket.”

She also says the benefits that come with signing up for Housing Connector are advantageous for vulnerable people who aren’t used to living on their own and are taking on a new, unfamiliar responsibility.

“[Housing Connector] offers mediation services between you and the landlord, or if you're getting treated unfairly, they can reach out on your behalf,” she says. “If you're struggling to pay your rent, you can have them help you to reach out and communicate. And then after you're there for three months, say there's an emergency and your car breaks down and you have to spend all your money on that—they offer up to three months of emergency rental funds to help you, because the goal is to establish some stability.”

We are proud of our team members who have accessed the services provided by Housing Connector, and couldn’t be happier to see them get their own set of keys and build a stable future for themselves.

In her short time at Pallet, Tonya has embarked on her recovery journey, found housing after experiencing homelessness, and set her sights on a skilled future career.

Tonya knows Everett like the back of her hand. She spent most of her childhood on the north side of town but has lived in various neighborhoods throughout her life. So it seems fitting that now, after a decade of living on the streets of her hometown, she’s found a new path at Pallet and already moved into a place of her own mere steps away from HQ.

Although she was born the middle child of five siblings, Tonya grew up as the eldest in the house, as her two older sisters lived elsewhere with other relatives. She was a natural athlete, playing basketball, volleyball, and running track for her high school teams.

Her stepdad was not only a solid supporter of Tonya and her siblings, but also played the role of coach in her athletic training. But even with bright prospects to play on a college level, Tonya felt as though something fundamental was missing due to her unconventional family dynamic.

“In high school I had a lot of scholarships to play different sports for different colleges, but my family was really broken, and I was looking to fill some kind of void,” she explains.

Tonya had her first son at age 15, which contributed to the loss of all her scholarships. Despite this massive shift in planning her future alongside the new responsibilities of becoming a mother, she worked tirelessly to graduate high school on time.

This feeling of accomplishment was short-lived. Out of school, Tonya got a full-time serving job out of necessity, which allowed her to secure her own apartment. Then she began using substances.

Life quickly began to spiral: she lost her job and was evicted after taking out short-term loans and falling behind on payments. Feeling lost and insecure about her ability to care for her child in such a tumultuous state, Tonya called her oldest sister, who promptly came to pick up her son and raise him in eastern Washington.

The lack of structure and trauma of living unsheltered caused Tonya to enter survival mode. She lived day-to-day, often couch hopping to friends’ houses or scraping together enough money for a motel room for the night.

“I was just really trying to figure out how, and where, I was going to sleep,” she says. “It was really hard being a young female, homeless out on the streets.”

In the final several years of being unhoused, Tonya lived with her boyfriend in a tent. She says they often wouldn’t be able to get into nightly shelters due to a lack of beds, and they weren’t interested in being separated.

During this time, they routinely talked about their hopes of getting clean. One day, he returned from the library to announce he’d arranged appointments to apply for a recovery program. From then on, they fully committed to sobriety and moved into separate sober living houses. Tonya immediately knew she made the right decision upon moving in.

“Oh my gosh, it saved my life,” she beams. “The structure has been great for my first year of sobriety. I really have been able to actually work on my consistency with my kids, with showing up for myself. I have so much support at that house. It’s been great, I love it.”

It was there that Sarah, her house manager, told Tonya about Pallet.

“She was telling me about this opportunity for people like us, who have a record, who don't have a lot of job experience, who have been homeless,” she recalls. “And I just thought it was a great opportunity to broaden my horizons when it comes to working and figuring my life out. So I suited up, I showed up, I tried it out, and now here I am.”

Tonya says she finds fulfillment working on the production floor and joining the deployment team to assemble shelters at new Pallet village sites.

“I feel accomplished,” she explains. “I feel like I'm actually doing something worthwhile, like I’m actually doing something good and not just wasting space. I've always felt like I've just been wasting space for a long time.”

In the short time participating in Pallet’s Career Launch PAD, Tonya has accomplished tremendous growth and plans to use her new skills to pursue a career as an HVAC technician. She says she’s not only enjoyed the hands-on lab sessions in the pre-apprenticeship program, but also taken a liking to the applied mathematics required for this skilled trade.

Outside of work, Tonya’s also made great strides with her family. She has moved into her own apartment with her boyfriend along with her two youngest kids. She’s close with her mom, who is now six years clean. Her own recovery is strong.

Given the progress she’s already made, we’re eager to see what great things await Tonya with her next steps.

Tonya's Progress Update: January 2025

Sometimes progress is small steps, other times it’s great strides.

Since starting Pallet’s Career Launch PAD four months ago, it’s decidedly been the latter for Tonya.

“I moved into my apartment and I’ll have a year clean next month, and I got my oldest son back in my life,” she says. “I got a gym membership—I vowed to never touch the basketball again when I started using drugs, but now that I’m clean I’m getting back into it. I’m gonna go get my license next week. Everything seems like it’s going smooth.”

Starting out, Tonya had her reservations about starting the program and getting back into a classroom setting. But once she gained some momentum, her concerns faded away.

“I was nervous in the beginning because it's been a long time since I've had to do any kind of schoolwork and be consistent with anything in my life,” she reflects. “So I was definitely nervous, but as I got the hang of it, it's definitely gotten me excited and it’s been smooth sailing since then. So I'm not even nervous about it anymore.”

One thing that surprised Tonya was how much she enjoyed the math components in the CITC program. She never thought she liked the subject in high school, but that changed when it was applied in the context of knowledge she would need in her future HVAC career.

“Back in school, I told myself: ‘I’m not good at it, I hate it, I can’t do this,’” she explains. “I’m coming into it this time as an adult with experience. In the beginning I was surprised that once they touched base on the course work, I felt like, ‘Oh yeah, I kind of like this.’ And then I got the hang of it.”

After getting her first grades in the mail and completing certifications in safety, CPR, and tool operation like the forklift and jackhammer, Tonya’s confidence his risen and showed her how capable she is.

“We got our first grades in the mail, and when I saw how good I was doing, I was like, ‘Wow,’” she says. “Like, ‘Wow, I’m really doing this.’ And it’s a really good feeling of accomplishment that you’re actually doing stuff for yourself. That made it feel real.”

Week to week, the schedule of attending classes at CITC and working at Pallet the rest of the week is working well for Tonya by setting up structure and expectations for herself.

“It helped me with routine and discipline,” she says. “I know what I need to do, I know how to prepare for the week: for school, for work. It’s a good transition, a different way to live. This time last year, I had no kind of schedule. Nothing. So it’s very refreshing.”

Adjusting to this new way of life didn’t come without some challenges. Tonya says it’s been difficult keeping up with certain financial obligations, but she’s not giving up.

“In the beginning it was child support and then I got past it, and now I'm back in the same spot again,” she explains. “But it's just a matter of putting some work in to figure it out. So I'll get through it again. This is the kind of stuff that makes people want to quit their jobs to start selling drugs again: ‘I can't get ahead.’ But I've been working too hard. I have too much support. Why go backwards? There's always a way to get through it, you know?”

Having clear goals set for her future and seeing the progress she’s already made is what keeps Tonya going. She says showing up for herself and making good decisions for her kids is one of the best feelings she could have.

“I'm proud of suiting up and showing up,” she says. “I'm proud of myself for continuing to do something with myself on a consistent level. I like the fact that I’m setting an example for my kids—it feels good that people actually look up to me and come to me for advice or trust me with certain responsibilities and know that I’m actually going to be there. It’s a really good feeling.”

Tonya's Progress Update: March 2025

Life is often a balancing act. Between adjusting to her schedule at Pallet, participating in courses at CITC, having her kids back in her life, maintaining her own apartment, achieving a year clean, and even helping her mom after an electrical fire damaged her house, Tonya says “crazy busy” would be an accurate description of how things have felt lately.

Even so, she’s keeping her head up and taking everything in stride.

“I’m just trying to get back into the hang of being a mom,” she says. “But some things are natural. I’m just really trying to figure it all out.”

She says moving into her own apartment is a big step up and feels like the start of a new chapter.

“The fact that I have my own place is beautiful,” she shares. “I have my family, my man, and we’re starting to live our life correctly.”

Based on what she’s learned about finding a job post-graduation, Tonya says while HVAC is still on her radar as a career path, she’s open to other options. Her main concentration is finding a job after graduating the program that allows her to have a stable income, gain some work experience, and explore her interests.

“I shifted [my focus],” she explains. “I’m definitely still intrigued and interested. But in the meantime, to pay the bills I can just tap into something else and see if I like it. Because I don’t know if I’ll like it until I do it, you know?”

Along with her fellow Launch PAD participants, Tonya is currently taking classes focused on electrical, which will be followed by a section on plumbing. But she said learning carpentry skills during their class project building a doghouse was a recent highlight of the program—even if the process didn’t click until actually putting the hammer to the nail.

“I’m a hands-on learner: you can’t show me a picture or read a couple sentences about something and expect me to know what it is,” she says. “I’ve never dealt with carpentry, I’ve never dealt with tools until I worked here. So for us to go and make the doghouse and apply what we learned, that was me learning it. But in the end, the whole thing was fun.”

Tonya says that while she is eager to know what life will look like after graduation, she’s confident in her new skills and happy to pass on the same chance she had to incoming members of the program.

“I have gotten used to working here, I’ve got my routine down,” she says. “But at the same time, I’m excited to branch out and to give other people an opportunity to do what I did. I know so many people that could get started if they could just have a job like this.”

Ultimately, Tonya knows that her experience working at Pallet and taking courses at CITC will set her up to pursue her dream of going to college and attaining a career in social work, where she’ll have the chance to fulfill her passion of helping others.

Given how hard she’s worked to get where she is today, we know she has the drive and talent to make this dream a reality.

Meet the other three featured participants in Pallet’s Career Launch PAD and read their stories.

The combination of fair chance hiring and sponsorship in a pre-apprenticeship training program equips our team members to grow, advance their careers, and become the skilled workforce of the future.

From the very beginning of Pallet, we have placed our team members at the core of our mission to give people a fair chance at employment. We strongly believe that people are defined by their potential, not their past.

The majority of our staff have lived experience of homelessness, incarceration, recovery from substance use disorder, or involvement in the criminal legal system. Their insight is crucial in continually refining our products to best meet the needs of communities who have experienced the trauma of displacement in times of crisis.

With our Purpose-Led Workforce Model, we are taking the next step in helping our team grow and advance their careers.

What is Pallet’s Purpose-Led Workforce Model?

Our model is built on two major pillars: fair chance hiring and Pallet’s Career Launch PAD (Program for Apprenticeship Development).

While some organizations are classified as second chance employers, we define our hiring practices as fair chance—as many people aren’t given a first chance to begin with. We offer the opportunity for people to work and grow at Pallet HQ as manufacturing specialists, regardless of criminal record, incarceration, or former job experience. This part of our model is crucial: even though it’s been confirmed that the vast majority of formerly incarcerated people want to work, roughly 60% of those released from prison remain unemployed, struggling to find workplaces that ensure job security and upward mobility.

The second key piece of our model is Pallet’s Career Launch PAD. This program entails enrollment in an offsite 9-month pre-apprenticeship training course focusing on developing essential skills needed for a career in the trades, while simultaneously building on-the-job experience manufacturing shelters in our production facility. This structure means employees are guaranteed full-time pay for attending classes one day per week and working in Pallet’s production facility the other four. Upon graduating from the program, our team will be equipped to pursue apprenticeships in a variety of skilled trades disciplines.

Pallet’s Career Launch PAD would not be possible without our collaboration with the Construction Industry Training Council of Washington (CITC) and grants provided by Workforce Snohomish. We are proud and grateful to work alongside these organizations who are equally invested in creating the next wave of skilled trades workers.

Why is This So Important?

By creating this program with growth in mind, we are offering a completely unique opportunity for our staff: steady, fair compensation alongside tactical educational courses that will guide their future. Upon graduation from the pre-apprenticeship program, our team members will move beyond Pallet to build their careers, making space for a new incoming class to participate.

In many ways, our Purpose-Led Workforce Model mirrors our mission to provide emergency shelter for those who have experienced the trauma of displacement. Similar to how our shelters provide Pallet village residents the time and space needed to transition to permanent housing, this program offers our employees stability and a supportive environment so they can start their career journey.

“Over the past few years, we have worked hard to develop programs and create support tailored to the unique needs of our employees,” says Tracy Matthews, Pallet’s VP of Human Resources. “This new model builds upon the old one by continuing to stabilize and support our team members with lived experience, while adding the educational component of Pallet’s Career Launch PAD. This program offers a pathway to other opportunities, enabling us to launch 25+ people per year into apprenticeship programs and extend employment opportunities to more impacted and marginalized individuals.”

To get a more in-depth look at Pallet’s Career Launch PAD, follow the progress of four of the program’s participants: Gregory, Christa, Jeff, and Tonya.

You can learn about each team member’s background, experience, and how they will use their training to launch their careers and build a brighter future.

Make your voice heard: by voting in the election, especially on the state and local levels, we can help create communities where everyone has a place to call home.

As the November 2024 Election takes center stage, national discussions on presidential candidates and their policy platforms often overshadow other topics. However, for issues like housing and homelessness, decisions made in local elections can have a more immediate and profound impact. While federal policies set broad parameters and designate funding streams, local and state governments are often where real change can happen—especially regarding housing development, zoning, and homeless services.

During this 2024 election cycle, it’s critical to understand how different levels of government function and influence housing and homelessness policy—and why your vote all the way down the ballot counts.

How Local, State, and Federal Governments Shape Housing and Homelessness

Housing and homelessness are complex issues, influenced by a web of policies set at the federal, state, and local levels. While each level of government plays a distinct role, their collaboration is essential to creating sustainable solutions.

Federal Role

At the federal level, laws and programs provide the financial backbone for many housing and homelessness initiatives. Agencies like the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) allocate billions annually for affordable housing, shelters, and assistance programs. Other key players, such as SAMHSA and the VA, provide mental health, substance use support, and housing services for veterans. These agencies work with local governments and nonprofits to prevent and reduce homelessness nationwide.

Medicaid, managed federally and at the state level, also supports services like behavioral health care for those experiencing homelessness. Federal policies often set the stage, but the implementation of programs like housing vouchers, grants for affordable housing projects, and homelessness outreach often depends on local administration.

State Role

State governments act as a crucial intermediary and often set their own standards for addressing housing and homelessness as well. States determine how federal funds are distributed to cities and counties and may set additional housing policies tailored to their specific needs. For example, state governments may pass legislation that incentivizes the development of affordable housing by offering tax credits or grants to developers. They may also establish tenant protections, housing bonds, or rent control measures, which vary according to the political climate of each state.

Local Role

For those passionate about housing and homelessness, voting in local elections is one of the most powerful actions you can take. City councils, county boards, and mayors make key decisions on zoning laws, land use, public health and safety, and the allocation of local budgets for shelters and supportive services. For instance, zoning laws dictate where emergency shelters and affordable housing can be constructed, and can either exacerbate housing shortages, or encourage development for homes or mixed-use spaces.

Local governments can also create strategic plans to create more housing or end homelessness, and they are uniquely positioned to pass ordinances around public camping or shelter availability – which directly impacts those experiencing homelessness.

This interplay between federal, state, and local policies creates a patchwork of regulations and funding streams that can be difficult to navigate. Outcomes often depend on local officials’ ability to effectively manage across these systems, and therefore, these leaders play a vital role in how well your community addresses housing and homelessness.

Why This Election Cycle is So Important

This election cycle presents a crucial opportunity to combat the escalating housing crisis and growth of homelessness. Nationally, many are struggling with skyrocketing rents and a lack of affordable housing that is driving homelessness. The COVID-19 pandemic, inflation, and economic uncertainty have exacerbated these issues further, leaving more people vulnerable to housing insecurity. As a result, the leaders we elect in November will inherit the responsibility of navigating these challenges.

It's not just the high-profile races that matter—down-ballot races, like those for city councils and county commissioners, directly affect communities in a multitude of ways, shaping policies that affect renters, homeowners and those experiencing homelessness.

How To Get Involved

Since “down-ballot” races often receive less media attention, fewer people may be informed about local candidates and their platforms. This makes it even more critical to research local candidates and understand their positions on the issues.

There are many ways to learn about local candidates, such as attending town halls, visiting their campaign websites, or reviewing their voting records. There are also many ways to get involved beyond voting, such as volunteering for candidates, ballot measures, or with local advocacy groups.

Whether you are voting early, by mail, or on election day Tuesday, November 5th, remember that every vote counts—especially for local races where margins can be slim.

While national elections may shape the headlines, local politics shape communities. By making a plan to vote with housing and homelessness in mind, we can help create thriving communities where everyone has a place to call home.

By broadening housing and supportive service models that meet the needs of those fleeing domestic violence, we can prevent impacted families from experiencing homelessness.

Research conducted over the past two decades has produced staggering and concerning statistics that illustrate the link between domestic violence and homelessness. Nearly 20 people per minute are physically abused by an intimate partner in the U.S., equating to 10 million victims per year. 38% of all domestic violence victims experience homelessness at some point in their lives. And in a survey conducted on one day in 2016, out of 11,991 unfulfilled requests from adults and children fleeing domestic violence, 66% of those requests were for safe housing and shelter.

There are many factors that contribute to this connection. To make meaningful change in ending this epidemic, it is key to understand the systemic inequity creating barriers for individuals and families escaping domestic violence—and ultimately remove those barriers by providing compassionate, comprehensive support via shelter, housing, and services.

Why is Escaping Domestic Violence So Difficult?

Before this question can be answered, it’s important to note that this framing is, in itself, problematic and perpetuates a culture of victim blaming. It’s a more appropriate question to ask, “Why do abusers hurt their partners, and how do they prevent them from leaving the relationship?”

There are several immediate reasons why domestic violence survivors feel they cannot leave their abusive partners. In many instances, leaving can be more dangerous than staying, with abusers threatening to harm or kill their partner, child, or pet. Psychological manipulation can also cause survivors to feel isolated and cut off from crucial support networks, making them feel like they have nowhere to turn. The majority of survivors also experience financial abuse, where they either have no access to the household’s income, have been prohibited from working, or have had their credit score destroyed by an abusive partner.

Beyond these direct barriers preventing freedom from their abuser, survivors also face systemic obstacles. A lack of easily attainable resources such as emergency shelter options and transportation to service provision sites prevent victims from quickly finding support. Even in light of state and federal laws preventing housing providers from discriminating against victims, some landlords will refuse to rent to someone who has experienced domestic violence. Further, those who have immigrated to the U.S. face language barriers, fears of being separated from their children, and potential threats of family members in their home country.

Best Ways to Support Survivors

The most effective ways to help survivors of domestic abuse are to expand emergency shelter models, transitional housing, and services tailored to their specific needs—while concurrently improving accessibility of these resources.

Emergency shelter, specifically non-congregate options like Pallet that follow principles of trauma-informed design, offer survivors a safe and secure environment that allows families to stay together in their own private space. Transitional housing with integrated supportive service programming is also an ideal model for people escaping an abusive living situation, giving survivors the chance to achieve economic stability and physical well-being.

In 2023, roughly 10.4% of all beds within homelessness service systems were reserved for survivors of domestic abuse and their families. Expanding overall shelter space and placing a concerted focus on tailoring short-term housing solutions to the unique safety needs of survivors is needed. One example is allocating more funding to grants like those administered through the Office on Violence Against Women (OVW).

By understanding the challenges survivors face in seeking out help and providing easily accessible emergency shelter, short-term housing, and services that directly address their needs, individuals and families fleeing abuse will be better supported to achieve long-term safety and freedom.

If you or a loved one are experiencing domestic violence or abuse, please refer to the following resources:

National Domestic Violence Hotline

National Indigenous Women’s Resource Center

Battered Women's Justice Project Criminal and Civil Justice Center

National Health Resource Center on Domestic Violence

Ujima, Inc.: The National Center on Violence Against Women in the Black Community

National Latin@ Network for Healthy Families and Communities

Asian Pacific Institute on Gender-Based Violence

Treating homelessness as a crime is costly, ineffective, and does nothing to solve the root causes of this crisis. Now, more than ever, is the time to invest in real solutions.

Communities have long understood the implications of criminalizing homelessness. Even so, recent state- and federal-level policies—which permit incarceration as a response to people living outdoors in public spaces—ignore the fact that this approach is not a solution. Rather, it perpetuates cycles of poverty, addiction, incarceration, and, ultimately, homelessness.

Reenforcing this broken system is as costly as it is ineffective. Not only will parks, recreation trails, and city streets continue to be misused, taxpayer costs will spike due to increased encampment sweeps and putting unhoused individuals in jail and prison.

It’s long overdue to focus efforts and funding on real solutions: provision of stable shelter, housing, and supportive services that enable vulnerable populations to contribute to the economy and community at large.

Perpetuating Ineffective and Unjust Systems

Current policies seeking to justify the criminalization of homelessness willfully ignore the failure of past efforts. Punitive measures including incarceration, encampment sweeps, and implementing cruel initiatives like hostile architecture simply propagate a broken system that pushes unhoused individuals further from stable housing and employment.

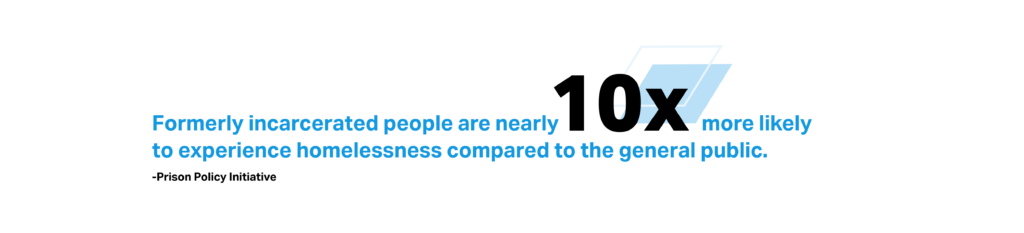

A significant part of this inefficacy is the fact that incarceration is, in many cases, a direct path to becoming unhoused. This “revolving door” effect has long been observed. Findings indicate that while a person who has been incarcerated a single time is nearly seven times more likely to experience homelessness compared to the general public, if that same person is jailed a second time, the rate spikes to 13 times higher. This means that if people are incarcerated on the grounds of living unsheltered multiple times, they are virtually guaranteed to return to the streets upon exiting the prison system.

Encampment sweeps, or the municipal practice of clearing public spaces of tents and other temporary or improvised structures, share the same level of ineffectiveness. When people living in these unsanctioned camps are forcibly moved, they often will relocate to another site. This of course accomplishes nothing but moving unsheltered groups from one location to another. A recent example in Washington D.C. illustrates this reality: after clearing out roughly 74 people living in McPherson Square, an estimated two-thirds of the group were still believed to be sleeping on the street.

It is fair that community members want to preserve their parks and recreation areas, especially considering they are not designed as living spaces and often lack adequate hygiene facilities, running water, and waste disposal services for unsheltered communities. However, when no alternative options are offered in conjunction with sweeps, the same displaced populations are likely to return to previous encampment sites.

As evidenced, the only true actionable solutions are building more affordable housing to mitigate the shortage of over 7 million rental units and creating broader, more equitable service programming for vulnerable and low-income populations. Offering transitional models such as emergency interim shelter with integrated service provision is another underutilized approach that creates pathways to more permanent housing. Incarceration, sweeps, and all other punitive approaches unequivocally fail to address these root causes or any of the conditions that exacerbate chronic homelessness such as substance use disorder, institutional racism, and generational poverty.

Futile Allocation of Public Funds

In addition to being ineffective and inhumane, incarceration (and the municipal, administrative, and reverberating economic costs associated with it) is far more expensive than simply building more housing. Many cities across the U.S. have reported dramatic cost savings to taxpayers when a focus was placed on providing more housing rather than cycling unhoused populations through jails, prisons, and the healthcare system.

One report released by the NYC Comptroller’s Office that shows the daily costs per-person of different approaches displays the cost-effectiveness of housing provision: compared to the $68 and $136 daily operating costs of permanent supportive housing and emergency shelter, respectively, one day of incarceration at Riker’s Island costs $1,414 and one day of hospitalization costs $3,609.

Another example in Denver indicates a similar trend. The study focused on individuals experiencing chronic homelessness who were in frequent interaction with the criminal legal system and emergency health services. When that group was enrolled in a city-operated supportive housing program, annual per-person costs for public resources such as jail, the court system, police, and emergency medical services lowered by $6,876.

Truthfully, the societal costs of incarceration go much deeper than daily operations and administrative fees. An estimated $370 billion each year is lost for people who have a criminal conviction or have spent time in prison—an enormous sum that could be spent on educational opportunities, buying a home, or a number of other economic investments that foster growth and community improvement. And when considering the massive amount of consequential loss associated with incarceration due to forgone wages, adverse health effects, and developmental challenges of children with incarcerated parents, the aggregate cost burden is believed to be roughly one trillion dollars.

These studies are incontrovertible proof that substituting jail and prison for housing is a gross misappropriation of taxpayer dollars, while providing no observable positive effects on solving homelessness.

True Solutions are Rehabilitative, Not Punitive

For years, it has been evident that real solutions focus on rehabilitating vulnerable populations, not jailing them. Time and time again, it’s shown that the solution is cheaper—fiscally and societally—than the problem. Comprehensive research has proven that criminalizing homelessness is expensive, wasteful of limited public resources, and harmful to public health and safety.

Now is the time to focus our collective efforts and funding on real solutions: creating broader shelter and housing models alongside comprehensive supportive services for displaced populations. Only then will we be able to observe progress in ending this crisis and restoring equity, safety, and dignity to our communities.

Data collected from sites across the country shows how the Pallet village model helps residents transition to more permanent solutions.

Every person’s journey to permanent housing is different. The trauma of displacement means every individual encounters their own barriers to finding a stable place to call home. And once someone exits this continuum of care that includes congregate and non-congregate shelter, supportive housing, and other forms of assistance, their success story often goes undocumented.

Although it is challenging to track a person’s progress through the housing continuum with accuracy and consistency, it is crucial to seek out this information and ensure our approach is effective. Pallet’s mission is to provide the supportive environment needed for displaced populations to move onto permanent housing, and this data tells us if our model is working and how we can improve our methods to best suit the needs of every village resident.

Establishing an Open Dialogue is Key

Our partnerships with village service providers are essential in both tracking residents’ progress and gathering context for what resources are needed in each unique community. Site locations across North America are faced with specific root causes of displacement, meaning there is no “one size fits all” solution. This is why once a village is built, our work isn’t finished: details like ongoing operations, maintenance needs, and supportive service provision all tell a distinct story that informs the future of Pallet.

Survey responses from village operators show that on an average day, 10 people move from an existing Pallet village to permanent housing. This tells us that in a broad sense, the pairing of dignified shelter with wraparound services like food and water, hygiene facilities, healthcare, counseling, and employment placement programs are effective in equipping residents with the tools necessary to transition to more permanent solutions. This trend works out to 3,200 expected transitions per year.

Measurable Success

Our ongoing relationships with service providers also bring to attention success stories like Tim’s, who found his own apartment after living in the Salvation Army Safe Outdoor Space in Aurora, CO. Connections to a state-sponsored pension program via onsite staff and help from the Aurora Housing Authority were instrumental in leading Tim to his own home, showing an effective model tailored to the individual needs of each resident.

Vancouver, WA’s approach to address their homelessness crisis, centered on a robust scope of resident services, has also proven success in helping vulnerable individuals on the path to housing. Their first Safe Stay community, The Outpost, reported 30 people moving to permanent housing since opening. Meanwhile, Hope Village achieved 14 transitions in their first year of operations, attributing resident success to a compassionate, healing communal environment with resources including meals, food bank deliveries, clothing, transportation, and assistance obtaining legal identification.

A Way Forward

Aurora and Vancouver are just two examples of sites that have experienced success with the Pallet village model. We believe that while interim shelter is a crucial part in creating safe spaces for vulnerable people to stabilize, it takes a breadth of additional support. This is why we view our product development through the lens of trauma-informed design and lean on our lived experience workforce for perspective: to ensure we are continuing to refine our mission to serve displaced communities to the best of our ability.

By investing in this approach and making concerted efforts toward inclusive wraparound services, any city has the potential to provide displaced populations with pathways to stable and permanent housing.

Understanding the differences between affordable and attainable initiatives is key to a future of stable, equitable housing.

Skyrocketing rental prices, astronomical interest rates, insufficient supply: the severe lack of affordable housing options is not a new development. As of March 2023, a shortage of 7.3 million affordable rental homes was reported, disproportionately affecting low- and extremely low-income families and individuals.

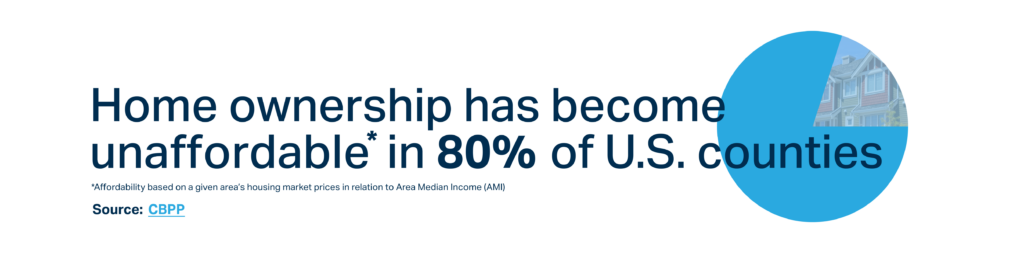

Housing affordability has become a chronic challenge—homeownership has been deemed unaffordable in 80 percent of U.S. counties—prompting policymakers to address this crisis through a variety of affordable housing initiatives. But to make a true impact on housing initiatives, understanding the distinction between "affordable" and "attainable" housing is crucial. While affordable housing targets specific income brackets, attainable housing places a focus on removing a slew of barriers and bringing suitable options within reach for a wider demographic.

Challenges in Housing Attainability

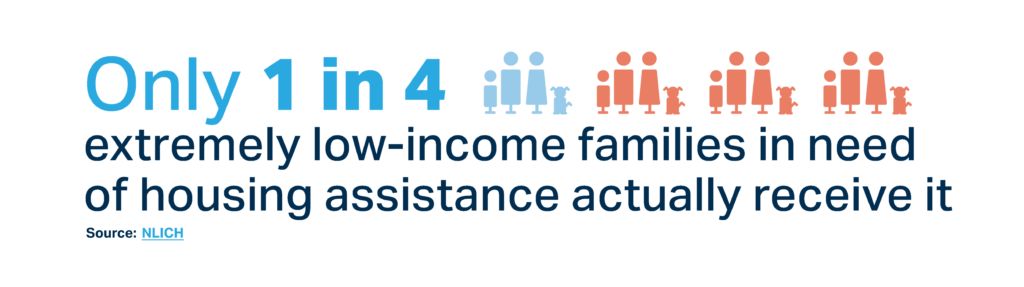

Despite numerous federal programs aimed at providing affordable housing, a significant gap exists between demand and available support. Strict eligibility criteria and additional screening processes often exclude vulnerable populations from assistance: one in four extremely low-income families in need of housing assistance actually receive it. This leaves an estimated 40.6 million Americans burdened by high housing costs, where more than 30 percent of their income is spent on housing and limits their ability to meet basic needs.

Various systemic barriers, including discriminatory practices and economic thresholds, also hinder a person’s access to attainable housing. Landlord discrimination against housing voucher holders, coupled with restrictive zoning laws, further exacerbates the crisis. Moreover, individuals lacking necessary documentation or with legal system records face significant challenges in securing stable housing.

While housing assistance programs like the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit and the Housing Choice Voucher Program play a crucial role in federal housing strategies, recipients face significant disadvantages including resource limitations and systemic biases. In particular, public housing has experienced a history of mismanagement and underfunding, perpetuating generational patterns of poverty and instability.

Proven Solutions to Improve Housing Attainability

To effectively break the cycle of housing insecurity, a multifaceted approach is necessary. This includes increased government funding, mixed-income housing developments, and expanded access to private capital for developers. Additionally, lowering the multitude of barriers facing vulnerable and low-income populations—accomplished through reforms in zoning laws, enhanced support for renters through federal programs, and amending punitive regulations aimed at formerly incarcerated individuals or those with legal system involvement—is a crucial step toward attainable housing solutions.

By prioritizing attainability, creating innovative partnerships, and developing more inclusive affordable housing initiatives, we can work towards ending housing insecurity while building economic stability and stronger social communities.

To learn more about solutions that address practical, accessible, and attainable housing for all, download our Attainable Housing White Paper.

To ensure our shelter design truly meets the needs of Pallet village residents, we spoke with some of the first people living in our new S2 units to gain feedback and insight from their experience.

The core of Pallet’s mission is to provide safe, secure shelter for people who have experienced displacement and offer a healing environment that helps residents on their next steps toward permanent housing. In developing our innovative S2 product line, we incorporated crucial feedback from our own lived experience workforce and applied key principles of trauma-informed design, knowing that this input is an essential part of creating dignified and comfortable spaces for every Pallet village resident.

Everett Gospel Mission (EGM), a village in our hometown, was the first site to receive 70-square-foot models of our S2 Sleeper shelters. We connected with four residents who had lived in the original shelter designs at EGM and now have moved to S2 units—Kenny, Jimi, Summer, and Erik—to hear their feedback on the new shelters and learn about their stories.

Kenny

Kenny has lived at EGM for nearly two years, originally moving to the site with his friend Libby after losing their housing. He had never experienced homelessness before or spent any time in congregate shelters.

He says since moving to the S2 shelter, he’s noticed the thicker walls have improved insulation and heat retention, reduced condensation, and made the interior more soundproof—a helpful detail since he’s teaching himself to play guitar.

“You don’t hear the rain as much: it’s quieter, way quieter,” Kenny said. “I can be a little louder in the brand new one compared to the old one, because I like to turn the amp up real loud, you know, and play the guitar and stuff. It stays warm in there a lot longer too I’ve noticed. Yeah, it’s overall better.”

Kenny gets along with everyone else living at EGM and doesn’t find it hard to make friends with others in the village. He noted how he likes the residential windows in the S2 unit: him and his neighbor will both open them up and talk from the comfort of their own space.

“It’s kind of cool, because the bed’s right there, so I just open the window and I can talk to the neighbor, and he’ll open his,” he told us. “He bet me four bucks that they would touch if we opened them.”

Kenny easily won that bet.

Jimi

Coming to live at EGM after being hit by a car while crossing the street, Jimi is using his time in the village to focus on sorting out medical issues and navigating a settlement in the case of a broken lease agreement. Sporting a leather jacket and a slick pair of yellow Chuck Taylor’s, he told us he’s grateful to have a temporary space after a tumultuous period of having nowhere to stay and limited means to transport his belongings to a storage space.

“It helps me not have to feel rushed,” Jimi said. “I got a pretty good head injury when I got hit. I don’t remember like I used to. I used to be able to multitask, but now I have to concentrate on one thing. So, being here gives me a chance to plan things, do one thing at a time.”

Jimi mentioned the new unit offers a calmer environment because it’s quieter.

“The thickness of the walls really makes a difference as far as noise,” he said.

Being able to store and arrange his belongings neatly with the integrated shelving is also a plus.

“[There is] a good place to hang your clothes,” Jimi said. “They have little shelves and a place to put hangers and stuff. That’s a lot better. Feels like you can organize your stuff a little easier.”

Summer

Experiencing homelessness for four years before moving into EGM, Summer has been a resident of the village since it opened. She finds comfort in decorating and caring for her plants and flowers, a hobby she picked up since moving into the community. She even arranged planters in communal areas in addition to the inside and outside of her own shelter.

“I did all the flowers that are out here and all the gardening and stuff,” Summer said. “I was doing it for myself already and they said, ‘Hey, let’s put in more for everybody,’ so I just ended up doing all of it.”

Summer told us she likes the ability to customize her shelter and make it her own. She’s added extra storage cubes and shelves, as well as hung mobiles she’s made from the ceiling. A mirror, a TV, and, of course, more plants make Summer’s shelter feel cozier and more unique.

“Everybody always is like, ‘Oh my god, your house looks so much different than everybody else’s!’”

She noted the size of the windows, larger bed, and improved heat circulation are notable details that make the S2 unit comfortable.

Overall, Summer said her favorite part of living at EGM is the ability to feel settled and have a space of her own.

“I could sit, you know, and actually stay and decorate it,” she explained. “I can feel comfortable and actually move in and not have to worry about police making me leave or having to drag everything with me. I have a place I can go in and sit down and have room for company and a TV.”

Erik

Erik has only lived at EGM for four months, spending the first two in the original shelter design before moving into the newer model. He said the increased square footage in the S2 unit is a significant improvement in maneuvering his wheelchair, and the larger bed is a better fit for him.

“I can move around a lot better in a wheelchair,” he told us. “To be able to sit in it and turn around makes a huge difference. And the bed is a little bit wider, so I sleep a lot better. It’s lower too, because I was tending to sit up against the bed in the older one. Those made my legs fall asleep and cut my circulation off. With the new style bed, that’s totally better: I can sit up on the edge of the bed and my legs won’t fall asleep.”

He also said the tighter seals on the corner connections and improved insulation from the wall panels helps keep the heat in.

“Having it hold the heat is a big difference too because it makes you feel like you’re in a better structure, since it’s not leaking out the seams.”

When Erik was hospitalized due to heart failure, he lost his housing, his car was impounded, and he found himself living on the streets. This was after working his whole career in the construction industry: first building houses, and then operating his own concrete company. He said it was a shock to exit the hospital and lose so much, along with experiencing displacement for the first time in his life.

Even with this devastating loss and coping with his medical issues, he is appreciative to be part of the community at EGM and have his own shelter.

“I think it’s great and it’s a great program, it’s a great thing [Pallet] is doing making those and making them available for communities to put them in and help people out,” he said. “Because I definitely need help. So it’s a beautiful thing what you guys are doing, because when people need help, you’re part of the solution.”

To learn more about how the design of our S2 shelters was informed by those with lived experience, read our blog.

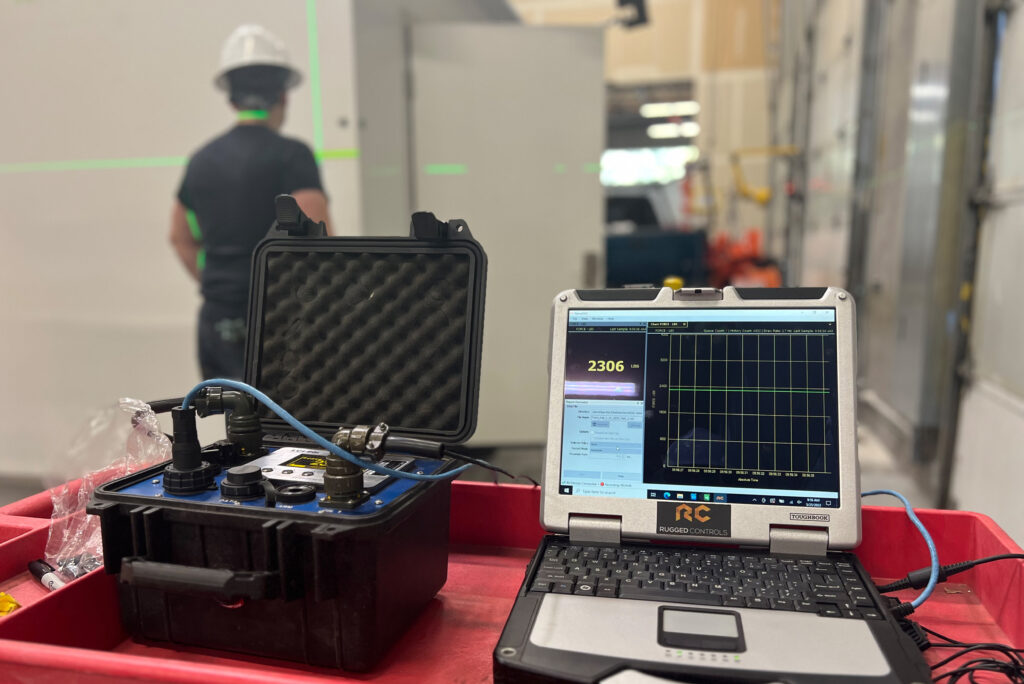

All the details that come together to make our new S2 shelter line were inspired and informed by feedback from our own lived experience workforce.

One of Pallet’s foundational elements is our lived experience workforce. As a fair chance employer, we provide opportunities for people who have experienced homelessness, recovery from substance use disorder, and involvement in the criminal legal system to build their futures.

We often talk about how our approach to designing Pallet shelters and implementing them within a healing community village model is informed by those with lived experience. In developing our S2 shelter line within the lens of trauma-informed design, these voices were crucial to ensure that our shelters provide private, safe, and dignified living spaces for displaced populations and encourage positive housing transitions.

There are many seemingly minute considerations that influenced the design of our S2 Sleeper and EnSuite models. To capture how important these details truly are for village residents, we gathered Pallet’s first Lived Experience Cohort—Josh, Alan, Sarah, and Dave—to describe in their own words how each design aspect is significant for anyone who has experienced the trauma of displacement.

Comfort

Significant changes in aesthetic, functionality, and fixtures make the S2 line a more comfortable living space overall. Smooth wall panels make the interior of each shelter more welcoming.

“The biggest thing is the aluminum [interior flashing] is gone,” says Josh. “So it feels like a home. It seems like someone took time to make it.”

When Josh was in Sacramento on Pallet’s California Roadshow, he noticed how attendees felt while touring S2 shelters.

“Almost everyone who walked in said, ‘This feels very warm. It’s so inviting to walk in here, it’s so open.’”

Dave comments on the effect this feeling would have on someone who has experienced homelessness.

“One of the most disturbing things to me when I was out there was coming to that realization: ‘I don’t have a f***ing home anymore,’” he recalls. “And to go into something that feels like a home, that you can call your little home, that’s really nice. That’s huge.”

Residential windows are another significant detail that Sarah notes.

“They give more lighting, so it doesn’t feel like a jail cell,” she says.

“They’re way better windows,” Dave adds. “[Residents] have a big, nice window to look out of now.”

Installing larger beds was also a noted concern, and the Twin XL is a more inclusive option.

“I think the larger sized mattresses are great,” she says. “Now villages can get twin sheets and covers and protective sheets that fit. And the fact that these new mattresses are waterproof, even the threading on the seams.”

The S2 EnSuite is Pallet’s first sleeping shelter with integrated hygiene facilities. Josh says the opportunity to have this kind of space with access to his own bathroom would have been a significant aid in his recovery journey.

“If I moved into the EnSuite, that would have blown my mind,” he quips. “If I was coming off the street or living in my Explorer like I was at the time, and moved into that, I might have been clean way sooner. Because it would’ve given me some hope that somebody cared.”

Safety Features

Pallet’s in-house engineering team created the S2 shelter line with safety at its core. In addition to the structurally insulated panels that offer durability and robust wind, fire, and snow load ratings, the elimination of exposed hardware in the interior is another detail that ensures safety for residents of all ages and walks of life.

Input from our lived experience team and feedback from Pallet village residents across the country also led to tweaks to the included fixtures, reducing the likelihood of essential safety functions being disarmed or damaged.

“We were pushing to get a cage over the smoke alarm, or something to prevent people from taking them off,” Sarah remembers. “Now [with the hardwired connection] you can’t shut off the power to the smoke alarm.”

The consideration that displacement affects different communities—from single residents with pets to families with young children—also influenced changes in other design elements of the S2 that may have gone unnoticed otherwise.

“I think the electrical panel is better: now we have the breakers on the outside and the plugs on the inside,” Josh adds. “So it keeps you from wanting to easily tamper with it.”

Dignity

Offering a more customizable layout and built-in wire shelving in the S2 line creates a dignified space for every Pallet shelter resident.

“Having a place to hang up clothes, that’s something I heard a lot when I was talking to residents in California,” Sarah comments. “That was a huge improvement, because if you’re still having to constantly live out of your bags and your suitcase, you’re not moving forward to get out of that survival mode.”

The ability to freely move the bed and desk is also a significant detail for people who have experienced institutional or congregate shelter settings.

“If I saw the bed set up in between two windows, I would say, ‘There’s absolutely no way I would pass out in between in between two windows,’” Alan quips. “I would sleep underneath the bed maybe. Because people walking past the windows, it just doesn’t make me feel very safe.”

Sarah agrees: “And then too, if you want to rearrange or just make it your own, everyone’s going to have a different feel of where they want to sleep on any given day. It gives you freedom. And if you have the freedom to live how you want to live, it gives you the sense of self-sufficiency rather than having to follow all the strict congregate shelter rules.”

Josh further highlights how significant this feeling of freedom can be when looking back on his own experiences.

“See, I would have never moved it, but having the opportunity to move it is a big thing,” he says. “Because when you’re in jail, your bed is where it is. Your seat is where it is. There’s no moving it around, so being able to move your house around like anyone else, it makes you feel more like a human being.”

Ultimately, our Lived Experience Cohort members agree that implementing these changes to create the S2 line advances our mission to help displaced populations transition to more permanent solutions.

“In the future when we come out with new products, it’ll probably be like, ‘Oh wow, I didn’t really think of this before,’” Josh offers. “But right now I think this is the best we can do. It really is, until we get more feedback on what the next thing is.”