Today, American Indians/Alaska Natives (AI/AN) experience the second highest rate of homelessness in the U.S. Our recent exploration of the impacts of homelessness on Native peoples lends perspective to the complex cause-and-effect relationship behind this crisis, and many of the same factors play into the myth of adequate funding.

Yet anyone unfamiliar with the data might understandably look at it like this: The federal government is obligated to right the wrongs of decades of historical traumas, so funding sufficient to end this emergency must reach the tribes. That is not true for several reasons.

Federal funding for tribal housing assistance has stagnated since 1998

A lack of affordable housing is directly tied to higher rates of homelessness on tribal lands. But despite helpful increases in the past few years, Indian Housing Block Grant (IHBG) funding levels have remained largely static in the quarter-century following its start in 1998. Because the IHBG is the primary source of funding by which tribes provide affordable housing on reservations, an inadequate contribution translates directly to a critical housing shortage.

An estimated 68,000 new homes are needed to eliminate overcrowding and replace inadequate housing on reservations – and an increase in population since that data was collected has likely worsened the shortage.

High Inflation and increasing reservation populations play a role

Though the dollar amount of IHBG funding has increased slightly over time, inflation has taken a toll in the 25 years since it began, eating away at the value of the contribution. It now represents only a fraction of the 1998 value—a serious impact considering that even at full 1998 value, these dollars did not meet the demand for affordable housing.

Meanwhile, reservation populations have increased since 1998, significantly lowering the per capita allocation of IHBG funding. In the period from 1999 to 2014, the per capita amount decreased over 33% – with real consequences.

Other factors combine to intensify the crisis

Barriers to development including limited private investment, low-functioning housing markets, and poverty mean that Native communities face some of the worst housing and living conditions in the United States. In nearly every social, health, and economic indicator, AI/AN people rank at or near the bottom. According to the latest counts, 1 in 4 AI/AN people were living below the poverty line, almost twice the national rate, yet only 12% of households said they were in assisted housing.

Much of the existing housing is insufficient and overcrowded. According to a 2017 study, homes in tribal areas had deficiencies that far exceeded the national rates of 1-2%.

And among AI/AN households in tribal areas, 16% are overcrowded, compared to 2% nationally. The practice of “doubling up” – living with friends or family despite overcrowding – masks literal homelessness and skews the data that government agencies rely on to allocate funding.

The result? Tribal housing assistance is in desperate need of an overhaul and an infusion of dollars.

Even if funding levels rise sufficiently to meet the affordable housing crisis head on, how much time will pass before conditions measurably improve on tribal lands? Construction is a slow process and, when tied to grant funding, often hindered by red tape that can add years to a project.

The tribes need solutions now, not five years from now. Nearly 80% of Native people no longer live on reservations, due in large part to living conditions there. This leaves many feeling disconnected from their culture and caught between two worlds, with no sense of belonging in either. Understanding this – and the points discussed above – illustrates how when we assume indigenous communities are getting the help they need, we only leave them more vulnerable to going unnoticed.

There are signs of progress. With All In: The Federal Strategic Plan to Prevent and End Homelessness announced in December 2022, the government acknowledges the work to be done both nationally and specifically to improve conditions on tribal lands. The intent is to “ensure state and local communities have sufficient resources and guidance to build the effective, lasting systems required to end homelessness.” One of its four main strategies: Increase access to federal housing and homelessness funding for AI/AN communities living on and off tribal lands.

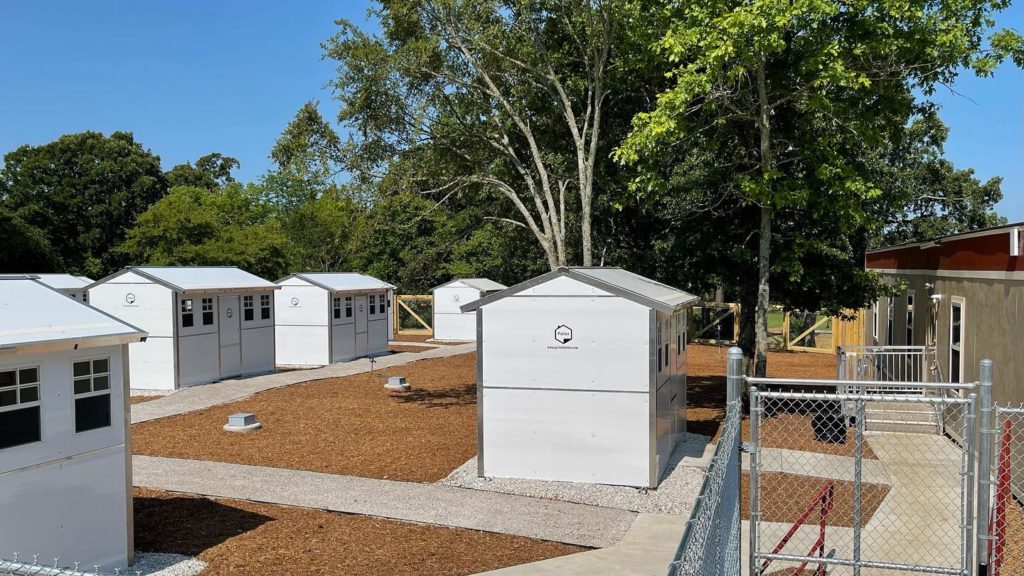

While long-term solutions are put in place, Pallet bridges the gap with immediate transitional housing and connection to wrap-around social services – a proven model for success. At the end of 2022, we built a shelter village on the Tulalip Tribal Reservation in Washington state – a good example of a solution tailored to its community. The Tulalip Tribe will run it with the ability to provide culturally appropriate resources. We know there’s no one-size-fits all approach to solving homelessness. But when advocates can create an ecosystem of support such as this, there’s potential for great progress.

6 impacts of homelessness unique to indigenous communities

Get them in a room together and Jennifer and Alan laugh – a lot. The two first met each other a handful of years ago when they were living on streets of the Tulalip Indian Reservation in Washington. Today they’re co-workers at Pallet. Their witty humor makes them a dynamic duo dropping hilarious one-liners as they tell stories about their past. Indeed, they can have a crowd in stitches.

“I relate to many of the people here because we can laugh about things that most people would get appalled by,” Alan says in admiration of his co-workers, many of whom share similar lived experiences.

Jennifer agrees – they have witnessed the darker sides of life. But, she says, they’ve risen above them. “It’s like, you guys, we have overcome so much and we’re killing it now. We are rock stars,” she says, laughing.

She and Alan are proud to have surmounted substance use disorder and other challenges that are, truthfully, nothing to laugh at. Right now though, they’re excited to be working on Pallet shelters for a new village on the Tulalip Reservation where they were once unhoused themselves.

“I’m super happy about the village because there’s a lot of my friends still stuck out there in Tulalip, doing the same dumb [stuff] I was doing,” Alan says. “Now they can potentially move into a Pallet shelter. And the guy that they used to get high with and go commit burglaries and crazy [stuff] with, is the same [guy] who built that shelter for them.”

Alan’s a machinist. He creates the individual parts that form the skeletons of our shelters.

Jennifer works in maintenance and repairs; she just transitioned from being an HR safety specialist. Sometimes she also works onsite erecting the villages. She feels a connection to the people who move into the shelters.

“When you get the opportunity to go out in the field and watch people take down their tents and cry and be so thankful and tell you that as they’re moving their stuff into a unit” it’s powerful, she says.

Years of substance use and cycles of recovery and recidivism led to Jennifer and Alan living unhoused on the Tulalip Reservation in the same circles for about six years. Alan lived in a tent surrounded by 30 other tents. Jennifer sold drugs.

“I needed drugs, she had drugs, that’s how we met,” Alan quips.

“As long as I could keep drugs in my pocket, I was ok. It meant I had money,” Jennifer explains.

Life on the streets was extremely hard both physically–such as defending oneself from attacks—and emotionally; there’s often a loss of self-worth, Jennifer says. “You have to be a survivor. You have to do things you normally wouldn’t do just to get by.”

“People tend to think of drug addicts as being weak,” Alan says. “But it’s the opposite; you’re battling every single day. You’re not thinking about tomorrow, you’re thinking about how am I going to get through today. You’ll worry about tomorrow when tomorrow comes.”

Through their own journeys and fortitude, Jennifer and Alan both eventually entered clean and sober houses. Jennifer started managing the women’s house, and Alan, the men’s. Jennifer came to Pallet about a year before Alan and found the structure and accountability she needed to start rebuilding her life. Soon she was promoted to HR. “Alan’s manager referred him to me as a great worker and we needed people,” Jennifer says. She helped hire him.

“I just love that when I got into HR I could get more people in and be a fair chancer,” she says. “To watch your fellow co-workers thrive and grow, you get so much reward out of that.”

Being part of a fair chance employer feels like an extension of how she, Alan and others provided support to each other on the streets. “Being in the circle of addiction, you still take care of each other,” she says. “Some days are harder than others. You’re just ready to give up and you just need that one person to believe in you.”

With co-workers who believe in them and stable jobs, Jennifer and Alan are thriving. Alan just moved into an apartment and got his license back. Jennifer lives in her own place with her daughter.

Through their work on Pallet’s 100th village—the Tulalip village—Jennifer and Alan are striving to provide these critical transitional shelters to friends who are still unhoused on the reservation.

“For me, it’s about being part of solving a bigger problem,” Jennifer says. “What makes me excited about the Tulalip build is coming from there–it’s literally closing that whole circle and being able to give back.”

6 Impacts of homelessness unique to indigenous communities

By Adrienne Schofhauser

“Native people were never homeless before 1492.”

It’s a poignant reminder from the Chief Seattle Club, a Native-led housing and human services agency in the city. In Seattle, Native people are seven times more likely than white people to be experiencing homelessness. While these rates are higher than most of the country, they represent a crisis that’s happening nationwide.

Decades of atrocities against Native people have produced a harsh reality: Today American Indians/Alaska Natives experience the second highest rate of homelessness in the U.S., according to the latest Annual Homelessness Assessment Report by the National Alliance to End Homelessness. As of 2019, Native Americans account for approximately 1.5% of North America’s population, yet they make up more than 10% of the homeless population nationally, according to the HUD report.

The reasons for these disparities are complex, but like many ethnic injustices in America, they’re rooted in the historical traumas uniquely experienced by these populations. Policies set up by the U.S. government to assimilate Native people had lasting impacts, and led to deep mistrust of agencies and resources.

It’s easy to assume the federal government’s partnerships with the Tribes would provide sufficient funding to right these wrongs. But the system is outdated and vastly underfunded. Largely due to this, nearly 80% of Native people no longer live on reservations. These impacts leave many Native people feeling caught between two worlds—with no sense of belonging in either.

Historical traumas

Actions by the federal government such the Indian Removal Act of 1830 and the forced assimilation of tens of thousands of Native children through boarding schools in the late 19th century may feel as though they’re part of a bygone era. But the traumas experienced by those who endured them have been passed down through generations of Native people.

In the boarding schools, Native children were stripped of their connections to their culture, forced to lose their language and traditions. They endured mental, physical and sexual abuses. These traumas had long-lasting, multigenerational impacts, creating personal scenarios in which it’s hard to seek help, trust authorities and systems, and ultimately establish stable housing.

The Chief Seattle Club said it sees first-hand how many Native people who walk through their doors still experience a “deep longing” for connections to their culture and traditions.

Mistrust in government agencies

These historical traumas carried in the bodies and minds of Native people through the generations have created a great mistrust of government agencies. The results are damaging: Even when assistance is available, few Native people may take advantage of those resources. According to Point-in-Time data, Native people access housing shelters at a lower rate than any other demographic.

When Native people do seek resources such as housing and employment, systemic and cultural barriers—such as implicit bias and lack of respect or understanding of cultural differences by people involved in the process—present big hurdles to securing that next step toward housing and financial stability.

In other words, when Native people take the initiative to push beyond their ingrained mistrust, they’re often met with an even higher hurdle—society’s historically negative perception of people who have endured unacknowledged hardships and harms.

Low counts lead to a lack of federal funding

Native Americans experiencing homelessness are severely undercounted in U.S. data. Certainly, mistrust in government agencies is one reason—when Native people don’t access resources, advocate services can’t generate reliable data. Another reason is simply their small population size, which makes it hard for homeless services and the U.S. Census to identify them.

The consequences of low and inaccurate counts can be devastating. Federal and other types of funding are tied to these numbers. Public policies are built around them. When Native people aren’t represented in the data—rendering them essentially invisible—public policies simply can’t address their needs.

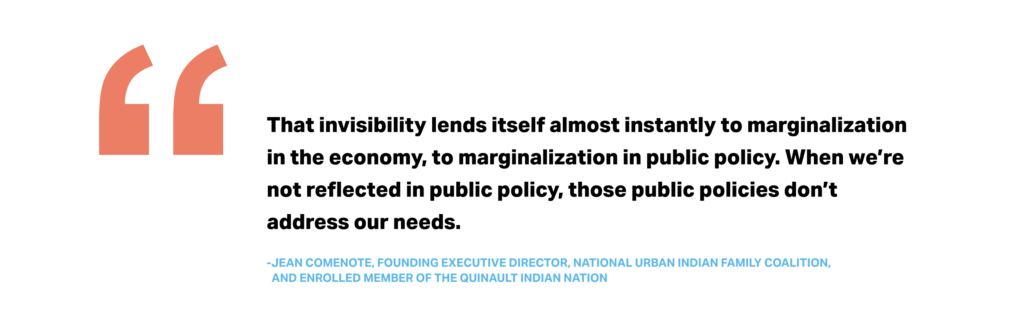

This plays out on tribal lands, where 23% of American Indian/Alaska Native households have incomes less than 50 percent of the federal poverty line. “Tribal nations rely on the U.S. Census Bureau to make sure that the count for Indian Country is accurate and complete to ensure proper representation and redistricting, equitable federal funding decisions and formulas, and access to accurate census data for local tribal governance,” Kevin J. Allis told a Congressional panel in 2020.

The reality is, the Indian Housing Block Grant (IHBG) funding, which provides affordable housing activities on reservations and Indian lands, has remained relatively stagnant since 1998. Meanwhile, inflation has eaten away at the value of those dollars. Additionally, the Native population living on tribal lands has increased over the last two decades. Because funding has not kept pace, services like housing assistance have suffered significantly.

Unfortunately, the negative consequences of these impacts can be highly masked on tribal lands. That’s because of a practice called “doubling up.”

Doubling up masks literal homelessness

Family members on tribal lands often provide shelter to friends and extended family lacking access to housing. Because of this, homelessness doesn’t so much take the form of individuals sleeping on the street as it does in doubling up. Individuals move from one overcrowded home to the next, a direct result of lack of affordable housing, which in turn, is the consequence of inadequate funding.

According to the U.S. Housing and Urban Development, between 42,000 and 85,000 Native Americans on tribal lands experience homelessness. Yet literal homelessness—that is, sleeping outside, in an emergency shelter or some place not meant for human habitation—is far less common. This is compounded by the fact that designated homeless services are also less common in tribal areas.

These circumstances have pushed many to seek opportunities off the reservations. But this comes with its own harsh realities.

Caught between two worlds

Having a credit history or understanding how to get an ID card are elements of everyday life in America. But for Native people migrating away from the reservation, these fundamentals can present major barriers to the first steps in applying for a job and establishing an economic foothold.

Additionally, mistrust and social discrimination continue to factor into their personal journeys.

Roughly eight out of 10 American Indians do not live on reservations. Yet very little federal funding is directed specifically toward them. Tribal governments usually allocate the funds they do get for life on the reservation. This leaves many Native people feeling caught between urban life and their reservation–or rather, abandoned by both.

Loss of spiritual connection

The major impacts of homelessness are felt across populations, from hazardous environmental exposure to safety risks, such as theft and murder. But unhoused Native people also face racial discrimination and a loss of connection to their culture and spiritual traditions.

Living on the streets makes it hard or impossible to practice their healing ways. Oftentimes, shelters and advocates aren’t knowledgeable about Native cultural issues. Nationwide, there’s a shortage of culturally competent outreach, which is key to engendering trust with unhoused Native people.

However, resources that are designed specifically for Native people are finding success. “We know that when our community gets culturally competent services, by Native people for Native people, the services are going to stick,” Janeen Comenote, founding executive director of the National Urban Indian Family Coalition, told Bloomberg.

If more resources address the challenges unhoused Native people face, the effects would literally be life-saving. According to New Mexico In Depth, the average age of death for unhoused white people is 45.6 years old. For unhoused Native people, it’s 37.5. And for Native women, it’s only 35.3.

Those are staggering numbers that hit us at the core here at Pallet. They’re proof that creative solutions are desperately needed.

We’re proud to be building a village on the Tulalip Tribal Reservation in Washington state; it’s our 100th village built. The Tulalip Tribe will run it with the ability to provide culturally appropriate resources. It’s an example of a solution personalized to its community. We know there’s no one-size-fits all approach to solving the homelessness crisis. But when advocates can create an ecosystem of support for reintegration–such as the Tulalip Tribe with these shelters—there’s potential for great progress to happen.

Pallet builds it's 100th village

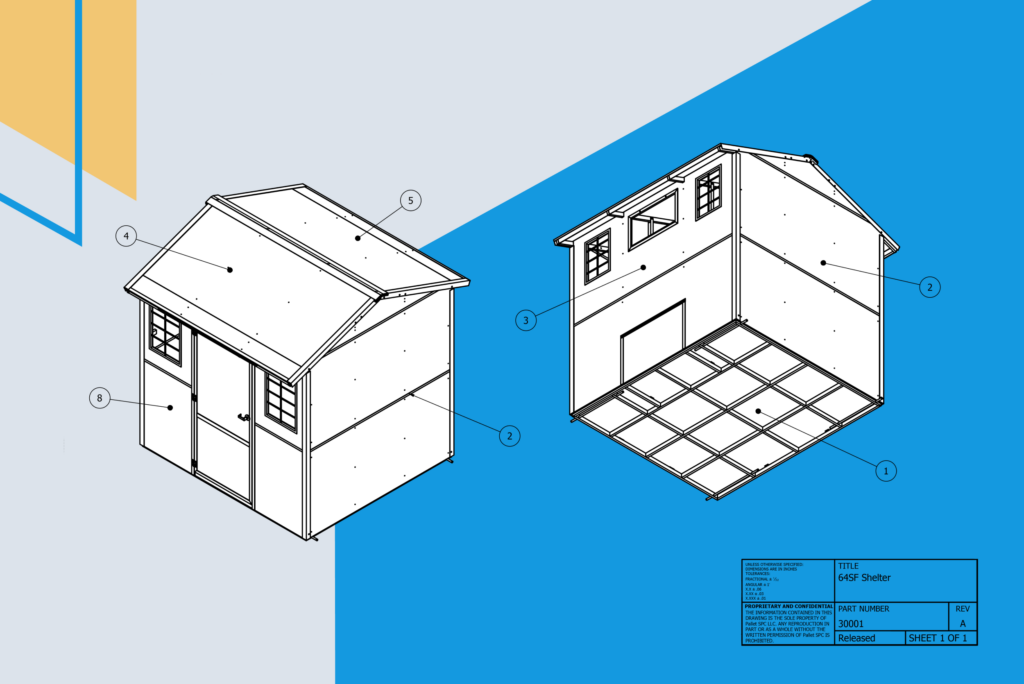

Just before Christmas, we crossed a milestone — building our 100th village. It’s located in Tulalip, WA which is just a short drive north of our headquarters. The location holds special meaning for some Pallet employees who previously experienced homelessness in the area and are now finding purpose in building transitional housing to help others in the community. The village is made up of twenty 64 sq.ft. shelters and one 100 sq.ft. shelter and was constructed in just two days by the Pallet deployment team. The Tulalip tribes will manage the site and provide on-site services for community members moving in over the next couple of weeks.

Build Breakdown

Pallet shelters are built by our deployment team – a dedicated group of nine staff members specializing in on-site shelter construction. They travel from city to city, building transitional shelter villages in communities for people experiencing homelessness. This team also offers advisory and training services for constructing Pallet shelters. The expertise and experience they bring create a seamless, replicable process.

A behind-the-scenes look into the process starts with the unloading of the palletized shelters from the delivery trucks.

Once the bases of the shelters are set in place, each shelter is built from the outside in.

Next, the side walls are built around the base and roof is built last.

The interior of the shelter is then constructed, which includes shelving, climate control, lights, electrical outlets, a folding bunk bed with a custom-fit mattress, a fire extinguisher, and a smoke detector. The last step in the building process is an inspection typically conducted by a Field Team Lead to ensure quality and to approve the site for city inspection.

Field Team Lead, James was one of the first people on the deployment team. He joined Pallet two and half years ago as a Manufacturing Specialist and was promoted to the role he has now. James is driven by our twofold mission — addressing unsheltered homelessness and building a nontraditional workforce through fair chance employment.

"I get to work with people that have not only experienced homelessness, but substance use disorder and incarceration and see them thrive. They're some of the hardest working people I've ever worked with," he explained. "Our shelters are transitional to help people who fell on hard times. The village is here to help you get through that and get back up on your feet."

100 shelter villages built and counting...

"Building our one-hundredth village shows the Pallet model is a proven and viable option. More and more cities are turning to us because they need creative solutions," said Pallet Founder and CEO Amy King. "At Pallet shelter villages, people come in and stabilize. By consistently engaging with a service provider, they can build trust and community together. This preparation allows them to sustain permanent housing once they get there."

Our first-ever village opened in Tacoma, WA, in 2017. The Tulalip location is the ninth village in Washington state. During the last five years we've set up shelters as far south as Hawaii and as far north as Burlington, VT.

The 100th build won't be our last. We'll continue to provide this valuable resource to communities who want to help their unhoused neighbors.

Tim’s story: From a Pallet shelter village to housing

As the year ends, we’re looking back at the stories we’ve shared throughout 2022. It’s been another year of growth, and we’ve evolved as a company — we’re now a Public Benefit Corporation and a certified Living Wage Employer. We’ve also expanded our footprint by building Pallet shelter villages in the northeast.

Notably, hundreds more people experiencing homelessness are staying in dignified shelter with a locking door and have access to social services. They can now stabilize and are working towards moving into permanent housing with the assistance of an on-site service provider. This year the Pallet model helped people such as Tim and others move out of temporary shelter and into their own homes.

Here’s a round-up of our top stories from this year.

1. Tim’s story: From a Pallet shelter village to housing

Tim became homeless after a series of distressing events. First, he lost his job, then the apartment building he lived in was sold. His lease wouldn’t be renewed, leaving him with 30 days to find a new place.

“Covid knocked on our door a couple of months after that, and it’s just been one speed bump after another that has culminated in where I am right now,” he shared. Tim went on to stay at a mass congregate shelter with hundreds of other people. Next, he moved to the Safe Outdoor Space (SOS), which has 56 Pallet shelters. “This is way better. You have your own key. You have four walls that you can lose yourself in or whatever, and you can ride out whatever unpredictable in your life, save up some cash and move on to your next step.”

Stabilizing in a safe, secure space positively impacted Tim’s life. After accessing social services, Tim moved into an apartment at the beginning of October. [Keep Reading]

2. A supportive little friend: Juan and Pepe

If you’re looking for Pepe – a tiny tan chihuahua – you may miss him at first. His favorite place to hide is Juan’s zip-up jacket. Pepe’s tiny head occasionally pokes out, just far enough to get ear scratches and peek around.

Juan, Pepe’s owner, loves to keep him close for cuddling. The duo first met a few months ago, in a tough time in Juan’s life. [Keep Reading]

3. Building community in Vancouver, WA

Recently Jerry and Sharon celebrated 26 years of marriage. This year they had more to commemorate than just lifelong companionship. At the same time last year, they lived outside and slept in a tent. The couple moved into Safe Stay Community, a Pallet shelter village in Vancouver, WA, when it opened in December 2021. The relocation was especially timely because of an unforgiving Pacific Northwest winter.

“It’s great compared to a tent. Heat’s good, especially in December when it’s colder than heck. Or April when it snows,” Sharon said. “And windstorms. We had a big windstorm that was taking tents down, but it never took ours down.”

“It’s a God send,” Jerry added. [Keep Reading]

4. Q&A: Mayor Cassie Franklin on addressing unsheltered homelessness

Pallet shelter villages are transitional communities for people experiencing homelessness. They provide the dignity and security of lockable private cabins within a healing environment. Residents have access to a resource net of on-site social services, food, showers, laundry, and more which helps people transition to permanent housing.

There are more than 70 Pallet shelter villages across the country, including one near our headquarters in Everett, Washington, which opened one year ago. Everett Mayor Cassie Franklin was instrumental in bringing the site to life. We held a webinar to discuss the affordable housing crisis, why unhoused people don’t accept traditional shelter, and the steps the city of Everett took to build a Pallet shelter village. Mayor Franklin provided good insight into these issues. Before becoming an elected official, she was the CEO of Cocoon House, a nonprofit organization focused on the needs of at-risk young people. [Keep Reading]

5. Change is possible, just ask Sarah

When Sarah sets her sights on a goal, she’ll inevitably be successful. Being resourceful and determined has served her well. Sarah joined Pallet as a Manufacturing Specialist at the beginning of the year. Joining the team was a full-circle moment. She vividly remembers seeing our shelters in downtown Portland a couple of years ago. In a short time, Sarah has made an impact working at Pallet. Working in the factory was a bit of an adjustment at first, particularly standing on her feet for long hours. Still, she got used to it and quickly excelled at the various steps of building Pallet shelters.

“They were bouncing me around to all the stations, and the supervisors kept saying, ‘normally people need to stay at a station for a certain amount of time before we move on, but you’re learning really quickly,'” she shared. “It helped give me that motivation and confidence.”

Within a few months, Sarah was promoted to Customer Service Coordinator, a new position on the Community Development team. [Keep Reading]

6. Building community at Westlake Village

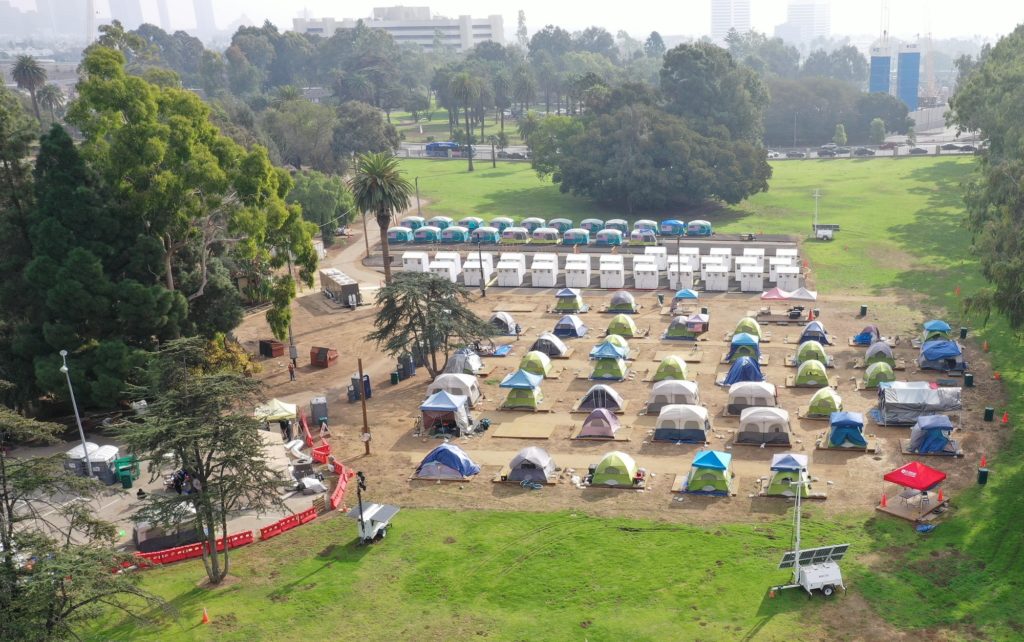

Two photos hanging from a fence greet visitors when walking into Westlake Village in Los Angeles. One has a placard underneath reading “Guest of the Month.” The other is titled “Employee of the Month.” The rotating designation encapsulates the spirit of the village and its values – building community, sharing positive feedback, and celebration.

The community of 60 colorful Pallet shelters and street signs is a transitional place for people experiencing homelessness. Residents have access to a resource net of social services, meals, hygiene facilities, laundry, and more. Urban Alchemy (UA) — a social enterprise engaging with situations where extreme poverty meets homelessness, mental illness, and substance use disorder — is the service provider for the site.

“My heart and compassion for the homeless population is huge. I believe that this is my calling,” shared Wanda Williams, UA Deputy Director of Residential Services. “We’re preparing them now for what may be next.” [Keep Reading]

7. Pallet achieves new status: Public Benefit Corporation

Pallet began in 2016 as a Social Purpose Company (SPC), the Washington state equivalent of a B corporation. As of 2022, we’re proud to announce that we’ve transitioned to a Public Benefit Corporation (PBC). It means we use profitability to expand our impact. As our business grows, the more jobs and shelter villages we can create to end unsheltered homelessness. The change reflects our growth as a company. PBCs are widely recognized across the country. More than 30 state legislators passed PBC statutes to make it easier for private businesses to establish themselves as a PBC or transition to one.

Think of a PBC as a hybrid of a nonprofit and for-profit organization. Our investment partners have allowed us to scale up quickly to meet the needs of the homelessness crisis. [Keep Reading]

8. Pallet is a certified Living Wage Employer

Investment in human potential is a core component of our mission. People who live in Pallet shelter villages are a part of a community where they have access to a resource net of social services, which enables them to transition to permanent housing. We’ve created a purpose-driven environment where employees are supported, and learning is encouraged.

As part of our commitment to creating sustainable jobs, we’re proud to announce Living Wage for US certified Pallet as a Living Wage Employer. The nonprofit organization granted the status after analyzing Pallet’s cash wages and benefits paid to employees. Third-party validation is another step for us to show business can be a force for good. [Keep Reading]

9. From second chance to fair chance: Why we’re changing our language

Language is ever-evolving. As society changes and grows, the words we use or stop using reflect who we are. At Pallet, we continually evaluate whether we’re using inclusive, destigmatizing language. We speak and operate in a way that mirrors our values.

Since our inception in 2016, we’ve identified ourselves as a second chance employer. At the time, it was a commonly used term to describe companies like us that aimed to build a nontraditional workforce. We focused on an applicant’s potential, not their past. As a result of this decision, it helped us design and manufacture shelter solutions firmly rooted in lived experience. But the term second chance employment doesn’t fit. It implies everyone has access to the same opportunities in life and squandered their first chance.

10. How Pallet shelters are tested for cold conditions

As part of our commitment to provide dignified space for people experiencing homelessness, we are continually improving our shelters. Conducting tests is one way to ensure Pallet shelter village residents are comfortable inside their cabins and safe from the elements. Recently two members of Pallet’s engineering team — Jordan, Design Engineer, and Jessie, CAD Designer — oversaw an independent assessment of our heaters and the 64 sq. ft. and 100 sq. ft. shelters. Specifically, we wanted an additional analysis of thermal efficiency in cold weather and the power consumption of the heaters.

Testing took place over four days at the SGS facility in Colorado. The shelters were placed inside a chamber that could reach -10 degrees Fahrenheit. [Keep Reading]

A safe place to regroup

Village of Hope, a new Pallet shelter village in Bridgeton, New-Jersey, will provide safe, stable transitional housing for people recently released from prison and on parole who have nowhere to turn and might otherwise face homelessness.

"Homelessness is a problem," said Bridgeton mayor Albert Kelly. "And this is one way of demonstrating how we can not only house those who are coming out of a halfway house, but perhaps we can expand on this for our homeless in our inner cities. And that's what our hope is."

Collaboration is essential in bringing a Pallet shelter village to life. Gateway Community Action Partnership, a New Jersey-based nonprofit, and The Kintock Group, a nonprofit that focuses on reentry programs, worked together to get the village up and running. It’s centered around six 100-square-foot Pallet shelters, and sits adjacent to a Kintock Group recovery residence. Residents will have access to shared bathrooms, picnic areas, and a community room.

Six residents at a time will stay for up to 180 days, supported by an ecosystem of essential services to help them acquire state ID cards, find work, access health and wellness care, and eventually secure permanent housing.

Each Pallet shelter provides a dignified personal space with a bed, a desk, heating and air conditioning, storage for belongings, outlets for devices, and a mini fridge—plus a door that locks for privacy.

A difficult transition

According to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), nearly 6.9 million people are on probation, in prison, in jail, or on parole at any given time in the U.S. Every year, more than 600,000 will be released from state and federal prison—many without anyone to assist with the challenges of reentry. With a history of incarceration, most will have trouble finding employment and housing, both crucial to building a new life.

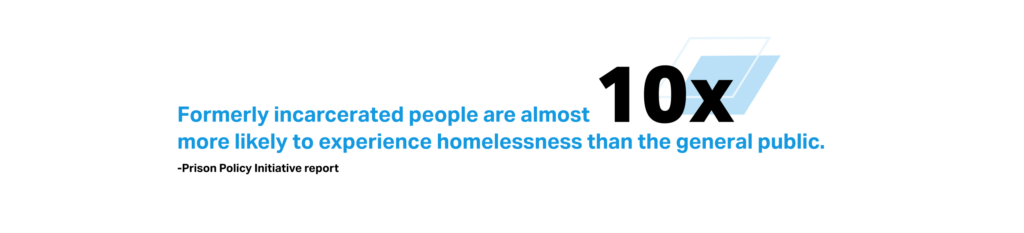

That difficulty is compounded by social and economic barriers that contribute to recidivism and homelessness. A Prison Policy Initiative report shows that formerly incarcerated people are almost 10 times more likely to experience homelessness than the general public. And according to HHS, nearly two thirds of prisoners are rearrested within three years of release, and half are reincarcerated. Without adequate support throughout the challenges of exiting the judicial system, chances of recidivism are likely to increase.

A way forward

There is no one-size-fits all approach to support those exiting the judicial system or seeking a path out of chronic homelessness. But stable transitional housing with close proximity to essential support services is a proven model.

Pallet shelters provide safe, dignified space in healing community surroundings. With a network of services on-site, people can begin to think about the next step. We believe people should be defined by their potential, not their past—and a positive future starts with a safe space to sleep and a supportive environment.

From second chance to fair chance: Why we're changing our language

In April 2019, Alex embarked on the path of recovery after using substances for more than a decade. Once he got his life back on track, Alex focused on setting and accomplishing goals, such as getting his license back and buying a car. He joined Pallet along the way and shared the challenges of his journey last year. Since then, Alex has accomplished even more. He shares the details below.

The following has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

Pallet: Things have been going well for you these days.

Alex: We bought our first home, which was huge. Going from a tent to owning my own home in three and a half years, that’s pretty big. I didn't even remotely think that we would be close to even qualifying for it, but my brother gave us his realtors information and we contacted them, and we got approved. Never thought that. With the market the way that it was at the time, I mean, houses were going like that (snaps fingers). We were lucky enough to only look at two houses. And the second house, we put an offer on, and our realtor called us that night and said that we didn't get it. We got out- bid, kind of bummed. But then the next morning she called and said that they retracted their offer and that we got it. So that was pretty exciting. It's a three bedroom, two-bathroom home and it's wonderful. We’ve got a big yard and yeah, it's great.

Pallet: What's it like to own a home?

Alex: It's phenomenal. Just having our own place and not paying somebody else's bills. And it's just a feeling that I didn't think was possible, at least at this stage. I had set a goal when I got clean to get a home in five years and accomplished it in three. I’m pretty proud of myself for that and Amber. She was a big part of it too. And we also got engaged. I think we're going to be setting a wedding date for September of next year. And we got a dog two months ago named Bud. He's a black lab. Then we got a new puppy, Yoda. He's a beagle bull. So, beagle and a pit bull. And he's just freaking cute. But he is a little ball of joy. Little terror, though. But the kids love him, which is great.

Pallet: You were also promoted. Why did you apply for the role?

Alex: Another huge step. Went from the manufacturing side and production to Inventory Control Specialist. It’s a brand-new position for this company. I saw an opportunity to take my career to the next level. I was almost at the top of where I was at and saw a chance to get something that will pay off. Another motivator was Damon (Supply Chain Manager) and the rest of the supply chain team themselves and them all being great people.

Pallet: What are your responsibilities?

Alex: Cycle counting and comparing the numbers that are actually on hand to what our value in QuickBooks says. When there are anomalies, I have to figure out what caused them and then figure out what needs to happen to fix them. Then what needs to happen to prevent them from happening again. It's great working for Damon. He is a phenomenal boss, and all the other supply chain team members are really great.

I have to take a course, CPIM which stands for Certified in Production and Inventory Management. It's an online college course that will help me with my role. I'm working on that and that is huge. It's a lot, a lot of reading, a lot of studying. And I have to take two exams to get the certificate, but once that's completed, that'll hold some good weight and hopefully help me with my role and my future career.

Pallet: You’ve reached several milestones in the last few years. Have you set new goals?

Alex: The next minor, small one is to buy a truck and a boat. My son loves fishing and so does Amber. So that's kind of something I see myself doing in the next three years. But career-wise I would definitely be finishing my CPIM course and hopefully moving up higher in the supply chain team. Obviously staying with Pallet. My heart is definitely with this place. Getting married, that's definitely something that we want to check off. I need to continue to move forward. In order for my recovery to be successful, I need to have those milestones. No matter how big or small, I still have to set some kind of goal to be successful with myself.

Pallet: Have your familial relationships changed since you’ve been in recovery?

Alex: When I fell off, they kind of stood back. But as they've seen the progress that I've made, it's all come back tenfold. It's been great. Especially the relationship with my dad. It always used to be when I’d call him, it'd be something that he'd have to worry about, why I'm calling, what's going on this time? But now when I call, he's excited and we can have an actual conversation. I've earned trust back. I've earned all of it back. Good standing with the families. Recently my dad, mom and my 84-year-old grandma visited, and they got to see my new home. We spent the weekend with them, and it was a good time.

Pallet: You’ve been in recovery for almost four years now. Do you stop often and take that in?

Alex: Time just flies by. I can't believe it's already been that long. But the more I can push that in the past — I still reflect on it from time to time and, you know, remember where I came from. I'm just so thankful every day that I got out. The blessings that I have today are just so great. My family is just wonderful. I love really everything about my life right now. It's just great. I want to continue going up and doing the next best right thing. It’s good.

By Bri Little

It's estimated more than 500,000 people across the country are unhoused. This growing statistic includes Veterans, children, and people who are employed. Some people are chronically homeless, while others stay in hotels until they can find stable housing. Homelessness affects communities across the country, from major metro areas to rural towns.

One common misconception about homelessness is that there are enough emergency shelter beds in any given city, but homeless people just don't want them. This myth is untrue for several reasons:

There is evidence that cities vastly undercount their homeless populations. Point-in-Time Counts, which relies on volunteers hand-counting the number of visibly unhoused people they encounter on a given night, has been under fire for some time. The King County Regional Homeless Authority in Washington state cited "harmful methodology" for not following the traditional approach for the 2022 Point-in-Time count. Instead, they received a methodological exception to conduct the count differently, allowing them to seek more qualitative data.

More evidence suggests cities have insufficient resources to house people, even temporarily. In 2019, the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals ruled that cities cannot enforce encampment sweeps if there are not enough shelter beds in Martin v. Boise. The ruling means that without enough shelter space for a city's homeless population, such as Seattle or San Francisco, city officials cannot enforce anti-vagrancy laws or prohibitions against camping in public parks or sidewalks.

Many cities with large homeless populations invest resources — which could be used for permanent supportive housing — in encampment sweeps. Sometimes people are only offered emergency shelter during sweeps, which are traumatic and disorienting events where their belongings are thrown away. Sweeps aren't a method to solve the homelessness crisis; it simply is a way to move people out of sight and around the city.

Due to the pandemic, shelters have closed or have diminished capacity. Further, since COVID precautions have been lifted in most places, it may be safer for individuals with certain health conditions to live outside than to be close to others.

People may not be able to stay in a shelter for myriad reasons. They include: desiring a sense of stability an emergency shelter cannot provide, wanting to stay with their pets/family, sanitation concerns, previous trauma related to living with strangers, domestic violence histories, and preferring vehicle residence. People already living outside have all their belongings with them, and they often cannot store all their possessions in a shelter.

It's harmful to pigeonhole people with various needs into a limited approach, such as emergency shelter. Then blame them for not being able to or not wanting to access a service that’s not one size fits all. Stable solutions that holistically meet their needs will help address this crisis.

Pallet shelter villages bridge the gap between living unsheltered and permanent housing by combining dignified space with a locking door and on-site social services. They are a proven model of success.

Bri Little is a DC-raised, Seattle-based writer and editor.

This post is part of an ongoing series debunking homelessness myths.

Part One: They are not local

Part Two: Homelessness is a personal failure

Part Three: Homelessness is a choice

Part Four: Homeless people are lazy

Part Five: Homelessness can’t be solved

Part Six: Homelessness is a blue state problem

Part Seven: Homeless people shouldn’t own pets

Homelessness is a complex, nuanced issue that takes time to understand fully. Organizations, experts, and advocates within the homelessness field use specific words and phrases that aren't common knowledge. To help bridge the information gap, we've put together another list of terms to help you better understand homelessness-related issues.

The list addresses metrics the federal government uses to determine who qualifies for aid, programs available to states to help unhoused people get back on track, and more.

1. Non-congregate shelter

A non-congregate shelter is an emergency shelter that provides private sleeping space, such as a hotel or motel room. Pallet shelters are in this category because people using them have their own private space and typically aren't sharing it with a stranger.

2. Area Median Income (AMI) / Median Family Income (MFI)

AMI and MFI are often used interchangeably and are the median household in a given region. This statistic is developed by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) to determine applicants' eligibility for specific federal housing programs.

3. Rapid rehousing

Rapid rehousing is a housing model designed to provide temporary housing assistance to people experiencing homelessness. This short-term intervention moves people out of homelessness quickly and into permanent housing.

4. Housing choice voucher (Section 8)

The housing choice voucher program is the federal government's major program for assisting very low-income families, the elderly, and people with disabilities so they can afford safe and sanitary housing in the private market. Housing choice vouchers are administered locally by public housing agencies (PHAs). The PHAs receive federal funds from HUD to administer the voucher program.

5. Emergency Housing Voucher

The Emergency Housing Voucher (EHV) program is available through the American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA). Through EHV, HUD is providing 70,000 housing choice vouchers to local Public Housing Authorities (PHAs) to assist: individuals and families who are homeless, at risk of homelessness, fleeing, domestic violence victims, human trafficking survivors, or were recently homeless or have an elevated risk of housing instability

6. Housing First

The Housing First model prioritizes providing permanent housing to people experiencing homelessness. This serves as a platform for them to pursue personal goals and improve their quality of life. This approach is guided by the belief that people need basic necessities like food and a place to live before attending to anything less critical, such as getting a job, budgeting properly, or attending to substance use issues.

7. Single Room Occupancy (SRO)

An SRO is a residential property that includes multiple single occupancy units. If the unit doesn't have a food preparation area or a bathroom, those facilities are shared. During the mid-70s and 80s, there was a sharp decline in SROs in cities such as Los Angeles, Seattle, and New York. This housing option reduction is considered a contributing factor in the rise in homelessness.

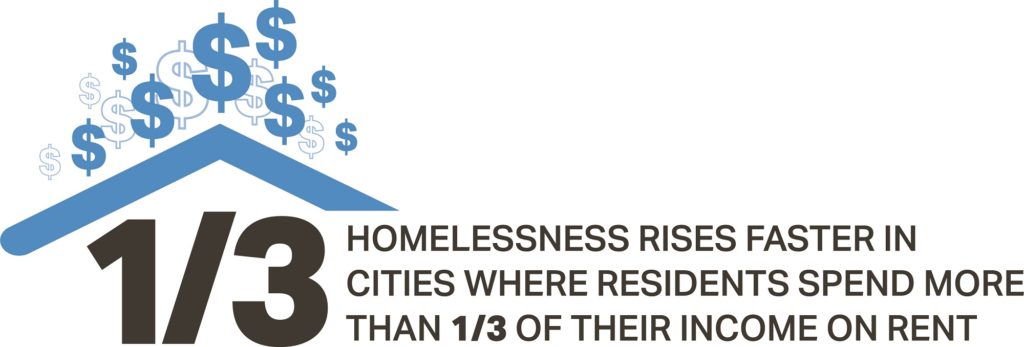

8. Affordable Housing

According to federal government standards, housing and utilities should cost no more than 30% of your total income. Publicly subsidized rental housing usually has income restrictions, dictating that tenants cannot earn more than 60% of the area median income. Homelessness rates rise faster in cities where residents spend more than one-third of their income on rent.

9. Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF)

The TANF program allows states and territories to operate programs designed to help low-income families with children achieve economic self-sufficiency. States use TANF to fund monthly cash assistance payments to low-income families with children and a wide range of services. The U.S. Department of Health & Human Services administers the funds.

10. Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP)

SNAP is a federal program that provides nutrition benefits to low-income individuals and families used at stores to purchase food. The program is administered by the USDA Food and Nutrition Service (FNS) through its nationwide network of FNS field offices.

11. McKinney-Vento Homeless Assistance Act

The McKinney-Vento Homeless Assistance Act is a federal law created to support the enrollment and education of students experiencing homelessness. McKinney-Vento is intended to provide homeless students the same educational opportunities as housed students by removing as many barriers to learning for homeless students as possible.

12. Hostile architecture

Hostile architecture limits how people experiencing homelessness use public spaces and discourages them from staying in an area for too long. Examples include a bench with an armrest in the middle, spikes, and boulders. Here's more on the impact of hostile architecture.

Defining the types of homelessness

Lacey has a smile that lights up the room. Her positive outlook is contagious, and she's a joy to be around. Lacey joined the Pallet team as a Manufacturing Specialist at the beginning of the year. In this role, Lacey moved from station to station in the factory to build the shelter panels. She enjoys working with her hands, so it's been a good fit.

"I loved putting the windows in. That was really fun. I did a lot of roofs.," she shared." I love working in production."

Within a few months, she went from manufacturing shelters at our headquarters to joining the deployment team, a dedicated group of staff who specialize in on-site shelter construction. Lacey has set up Pallet shelter villages across the U.S., from Sacramento, CA, to Burlington, VT.

"When I first started here, I heard about the deployment team, and I was just like, that seems like it just sounds like a dream job to be able to travel around. I'm a really hard worker," she explained. "I love the fast pace of deployments. I love running back and forth doing that stuff. I'm just excited."

In addition to being enthusiastic about being on the team, Lacey is thankful to be working alongside others with similar backgrounds. It was uncomfortable for her to disclose she had felony convictions to an employer in the past. She shares one of her experiences, "I had an interview, and the lady was just looking at me just crazy the whole time. I felt extremely judged. It was awful."

Lacey’s interview experience was different at Pallet because we're a Fair Chance employer. We believe in people's potential, not their past. More than half of Pallet staff are in recovery, have experienced homelessness, and/or have been impacted by the justice system.

"To be around a bunch of people that have been where I've been and are striving to go where I want to go — it's a good environment," she added.

Next month Lacey will celebrate being in recovery for two years. A tattoo on her forearm that says "thriving, not surviving" reflects how far she's come. Her substance use disorder began with a back injury she received at work when she was 19. A doctor prescribed her OxyContin. She used it to alleviate her pain for several years, but Lacey says the opioid shouldn't have been the treatment. Later, she had two laser treatments which technically negated the need for OxyContin.

"I had no idea that it was synthetic heroin. I had no idea that opioids were so powerful. Then they were like, 'Okay, it's time to get off of it,'" she explained. "It was everywhere. Everybody that I knew was doing it. Everybody was just smoking these pills, and so I just started."

She continued to work, but maintaining a full-time job became increasingly difficult. She moved onto other substances, and her life began to unravel. She had to quit her job, lost the home she bought a few years earlier, and had been arrested several times. She lived in a car and tried to survive. These were stressful times for Lacey that lasted many years, but after undergoing detox five times, and three rehab stints, Lacey was ready to make a change.

"You're not done until you're done, you know what I mean? You can go through the process over and over," she shared. "You can be forced to go to rehab, you can be forced to do whatever, and it does not matter."

Two years ago, Lacey was ready to stop using substances partly because a milestone birthday was approaching, and she wanted to live a different life. One where she had a stable place to live, employment, and no longer using substances.

After serving a sentence in county jail, Lacey moved into an Oxford House, which is recovery housing. Initially, Lacey wanted to live independently, but the peer-supported environment was a perfect fit. They share expenses, hold weekly meetings, and support one another. As part of recovery, Lacey attends Narcotics Anonymous (NA) meetings and tells her story to others. She can also spend time with her family, who live nearby.

After many years of tumult, Lacey is focused on leading a quality life. Pallet is proud to be a part of her journey. She exemplifies why diversified hiring practices are vital to our success. Lacey brings compassion and optimism to the team.

"Pallet is a place where you're welcomed with open arms. It's really freeing to be able to walk in here and be around a bunch of administrative people — who most likely have not been where I've been — and not be judged," she said. "I'm so grateful to have the opportunity to work and be able to gain my self-worth. I know what it was like to just give up on life basically."

Q&A: Mayor Cassie Franklin on addressing unsheltered homelessness

Pallet is the leader in rapid response shelter villages. There are nearly 100 active villages across the country where unhoused people can access dignified shelter with a locking door and on-site social services. With their basic needs taken care of, residents can focus on taking the next step.

Today Pallet is addressing unsheltered homelessness at scale and building a nontraditional workforce. Among the more than 100 employees, three people have been a part of this innovative endeavor since the beginning — Brandon, Cole, and Josh. They were early adopters of our mission and continue to play an integral role as we grow. All three have backgrounds in construction, so Pallet was a natural fit.

Here's a look at Pallet’s growth from their perspective.

Pallet is born May 2016

Pallet began with the idea of sheltering displaced populations, and it took some time to design the physical structure. Our engineering team created several prototypes before finding suitable materials and shelter sizes. Brandon recalls those early days.

"Lots of waves and roadblocks. They did a lot of research to figure out a lot of different things — fire rating to snow loads, wind ratings, square feet," Brandon explained. "I remember so many hurdles to get over because this was not a normal product. This was not a piece of wood."

Building the shelters was lengthy and tedious because the team cut each of the seven panels with a skill saw. By summer 2020, Pallet added a CNC router to the factory, which improved accuracy and efficiency. What initially took months to build can now be done in a fraction of the time. The manufacturing team produces 50 shelters a week.

"The evolution of this product is crazy," Cole shared. "You never would have thought it was going to have an air conditioner, a breaker box, and a heater and all these amenities that most of our houses have nowadays."

In the beginning, we held numerous demonstrations to showcase our shelters. It's where Brandon realized this was what he wanted to be doing — building dignified space for our vulnerable neighbors. At this point, he'd built a strong relationship with Pallet's co-founders, Amy and Brady King. Brandon believed in them and what they set out to accomplish. He ignored those who didn't think our transitional shelters would work.

"I knew it was a good idea. I just wholeheartedly knew it. And I didn't really have a reason why," Brandon shared. "I just knew that it felt good to do this, especially once we started doing deployments, then it really kicked in."

While Pallet worked to find its footing, only a handful of people were working for the company. Over time the number steadily increased, and today there are more than 100 employees. Josh was one of two in the factory building shelters when he started. Now he's surrounded by dozens of others and working on research and development. During company-wide meetings, he marvels at the number of people present.

"Every time we have an all-hands meeting, I get choked up every single time. I'm just blown away with how many people we have here," Josh shared. "The ways that we've grown and moved forward. It's just unbelievable."

Personal growth

As Pallet evolved, so did the team. Josh talks fondly of the relationship he built with Zane, recently retired Director of Engineering, and Greg, now Director of Operations. Josh said the two helped mold him.

"We all came from a construction background, and it was yell, scream, and get your point across. Zane taught us how we didn't have to do that. We could actually talk civil and come up with ideas together," Josh shared. "That's what I strive for in the R&D section. If I have an idea, I'm going to ask four people before I actually do it because what if I'm thinking wrong?"

For Cole, joining Pallet was an opportunity to move away from the grueling work of building permanent homes. He'd been working in construction since he was a teenager and thought he would be stuck in that role until he couldn't walk anymore. He's moved from Manufacturing Specialist to Supervisor to Manufacturing Engineer. Cole's time at Pallet coincides with his recovery journey.

"I focus really hard on a daily basis on growing as a person to better my people skills and my career," Cole added. "Being teachable and being humble and learning something new every day."

In addition to personal development, all three say being able to help those in need is a bonus for working at Pallet. They've each been able to talk with Pallet shelter village residents who are stabilizing and working on moving into their own place.

"It's not just about helping people. It's about changing people," Brandon shared. "When you can be there on-site and watch them move in and see how happy they are. That was probably the greatest reward I've ever had when I came to this company."

The inside of Tim's Pallet shelter in Aurora, CO, reflects what brings him joy. Denver Broncos and Colorado Avalanche jerseys brighten the space. A replica of a Detective Comics cover with Batman on the front is over the window. And dozens of Hot Wheels line the wall. Some are superhero-themed, while others are sleek racers inspired by real sports cars. Each is still pristine, encased in the original packaging. For Tim, they are much more than a toy marketed to kids.

"That is my salvation," he explained. "That takes me back to a more innocent time in my life where I can just lose myself in Hot Wheel cars. It was easy for me to do it as a kid. It's really easy for me to do it as an adult. They're the coolest things on Earth."

At one point, he had 3,500 Hot Wheels.

"They were my wallpaper in my dining room and kitchen of one of my apartments. I don't have that collection anymore, but I'm acquiring a new one," he added.

Tim is originally from Buffalo, NY, but he's lived in Colorado for years. He became homeless after a series of distressing events. First, he lost his job, then the apartment building he lived in was sold. His lease wouldn’t be renewed, leaving him with 30 days to find a new place.

"Covid knocked on our door a couple of months after that, and it's just been one speed bump after another that has culminated in where I am right now," he shared. Tim went on to stay at a mass congregate shelter with hundreds of other people. Next, he moved to the current site known as Safe Outdoor Space (SOS), which has 56 Pallet shelters. "This is way better. You have your own key. You have four walls that you can lose yourself in or whatever, and you can ride out whatever unpredictable in your life, save up some cash and move on to your next step."

Stabilizing in a safe, secure space positively impacted Tim's life. He no longer must navigate what he described as the chaos of being homeless. He's also enjoying independence.

The Salvation Army is the service provider at the site. Tim has been working with staff to take the steps necessary to move on to permanent housing. For example, he now receives income from the state's Old Age Pension Health Program (OAP), which provides financial assistance to elderly and low-income residents. About a month ago, he received the good news he's been waiting for. The Aurora Housing Authority let him know he was awarded a lifetime housing voucher.

"This voucher is a godsend," Tim shared. "With the little income that I have that the staff here helped me secure, I should be okay."

Because he has a voucher, he's only responsible for a portion of the rent. Now Tim is searching for an apartment to move into, which he's confident will happen soon. He's looking forward to getting back to the everyday life he led before becoming unhoused.

When asked what misconceptions people have about homelessness, Tim points out the absurdity of stereotypes and the assumption that all homeless people are the same.

"Nobody wakes up in the morning and says, 'I want to sleep on a piece of grass this morning. Or when I go to bed tonight, I want to sleep on a park bench or under a table or wrapped around a tree.' This isn't a social experiment," he shared. "The stigma, it's the word ‘homeless’ that scares the general public into a fit that they don't want nobody around them if they're homeless. We have to eat just like everybody else. We have the right to get our life back in order like anybody else that has a hard time."

UPDATE: At the beginning of October, Tim moved into a one-bedroom apartment, and he couldn't be happier. He credits several factors and a community of people coming together to help him navigate the path back to permanent housing. It includes the Salvation Army caseworkers, the Aurora Housing Authority, which granted him a housing voucher, and the ability to live in a Pallet shelter. Tim is grateful that he's now in a position to help others. He also has plenty of room for his Hot Wheels collection.

Building a path to permanent housing at Esperanza Villa

It's been another sweltering summer for many cities across the country. Days where temperatures reach triple digits are no longer as rare as they once were. Even the Pacific Northwest, an area known for having a moderate climate, hasn't been spared from record-breaking temperatures. As meteorologists issued extreme heat warnings, people did their best to stay cool.

Heat Wave Dangers

When the weather becomes unbearable, people without a stable place to call home are vulnerable to adverse health conditions and even death. According to an Associated Press report, "around the country, heat contributes to some 1,500 deaths annually, and advocates estimate about half of those people are homeless." Statistics from Maricopa County, Arizona — where Phoenix is located — show 130 homeless people died last year from heat-associated conditions. The number of deaths decreased from the previous year, but it was almost double the 2019 statistic. People who live in homes are also at risk for heat related death since having air conditioning isn't always a given.

To combat elevated temperatures, many cities open cooling centers. It's an essential tool because prolonged heat exposure can lead to numerous health problems. Groups at greater risk for heat stress include elderly individuals, those with chronic conditions such as heart disease, and people experiencing homelessness. According to the CDC, illnesses associated with heat include:

- Heat Stroke - occurs when the body can no longer control its temperature.

- Heat Exhaustion - the body's response to an excessive loss of water and salt, usually through excessive sweating.

- Rhabdomyolysis - also known as rhabdo, is a medical condition associated with heat stress and prolonged physical exertion.

- Heat Cramps - usually affect workers who sweat a lot during strenuous activity.

- Heat Rash - a skin irritation caused by excessive sweating during hot, humid weather.

Pallet shelter villages play a crucial role in helping our unhoused neighbors avoid the perils of living outside when a heat dome settles on an area. Our shelters are dignified spaces with a locking door and climate control which help keep the interior cool in the summer and warm in the winter.

Candace recently moved into a Pallet shelter in southern California. The week she settled in, temperatures in the area reached the mid-90s. After previously sleeping in a tent, she was thankful for a cool place to rest and recharge. "The AC is nice. It's a blessing to have the air conditioning," she said.

Cold Snap Concerns

Conversely, winter is also a hazard for our unhoused neighbors. Tents, tarps, blankets, and warm clothing can only do so much, especially when temperatures get down to single digits. If someone makes a fire or uses a camping stove for heat, that also presents hazards. Even when someone is living in their car, they can’t have it running all night to stay warm.

According to the CDC, hypothermia, and frostbite are the most common cold-related problems. When exposed to cold temperatures, your body loses heat faster than it can be produced. While hypothermia is mostly associated with very cold temperatures, the CDC says it can occur even at cool temperatures, above 40°F, if a person becomes chilled from rain, sweat, or submersion in cold water.

The heaters and insulation in the panels of Pallet shelters keep residents warm. Jay Gonstead moved into one of our shelters in Madison, Wisconsin, in December 2021. In an interview, he told a local reporter that when approached by outreach workers about moving into a cabin, he said yes because, "you knew you were going to be warm. You knew you were going to be safe here."

Rain, Wind, Snow

Rain, wind, and snow are also problematic weather events for people living outside. Tents and tarps offer little protection against those elements. Pallet employee Sarah, who experienced homelessness before joining the team, shared why it's difficult to live outdoors in those conditions.

"The winters and the rain were definitely the hardest, of course, because you're so cold and you're so wet. And then to be able to find dry clothes from whatever garbage can or from wherever you can find them," Sarah explained. She also had to escape from fires that started inside her tent while trying to stay warm.

Pallet shelters offer protection from rain, can withstand 110 mph winds, and have a 25lb per square foot snow load rating.

There are many other challenges to living outside that make it unsafe. At Pallet, we're working towards the goal of ending unsheltered homelessness. With each village we build, more people are brought inside, protected from the weather, and their basic needs — such as meals and showers — are met. Residents also have access to a resource net of services that enable them to move into stable, permanent housing. By providing this opportunity, people experiencing homelessness can focus on the next step, rather than solely survival.

Debunking Myths: Homelessness is a choice

Pallet shelter villages are transitional communities for people experiencing homelessness. They provide the dignity and security of lockable private cabins within a healing environment. Residents have access to a resource net of on-site social services, food, showers, laundry, and more which helps people transition to permanent housing.

There are more than 70 Pallet shelter villages across the country, including one near our headquarters in Everett, Washington, which opened one year ago. Everett Mayor Cassie Franklin was instrumental in bringing the site to life. Recently we held a webinar to discuss the affordable housing crisis, why unhoused people don’t accept traditional shelter, and the steps Everett took to build a Pallet shelter village. Mayor Franklin provided good insight into these issues. Before becoming an elected official, she was the CEO of Cocoon House, a nonprofit organization focused on the needs of at-risk young people.

Below is a lightly edited version of the conversation.

Pallet: How has the affordable housing crisis affected your area in the past three years?

Mayor Cassie Franklin: First of all, Everett has had a housing crisis. The West Coast has had a housing crisis for decades now, and the pandemic has only exacerbated that. So the last three years it has just gone out of control. Everett is about 20 miles north of Seattle. Seattle was always an affordable big city, and people would move to a more affordable working class community like Everett. Now Everett is also becoming unaffordable. I just actually had a conversation with one of our residents that her rent was going up $300 a month and she's on a fixed income. That is not going to be affordable, and that's going to lead folks like that individual into homelessness if we don't protect the affordability that we have in our communities.

Because affordable housing is for everybody. It is for our nurses, it is for our firefighters, our police officers, our baristas, our working families need affordable housing. Everett needs housing at all price points.

The homelessness crisis has escalated tenfold, I guess, in the same period. So I just want to say that they're both interrelated very important issues that we're working towards. And I see Pallet as a very important tool in addressing homelessness and making sure that we have pathways to affordability for folks.

Pallet: Can you discuss funding sources available to fund Pallet shelter villages or comparable models?

Mayor Franklin: Before actually all that federal funding that's available right now, we were interested in Pallet and interested in making it happen. So we started to work with the team to identify how we could do it using city-owned property. So that helps with the expense right there. If you take city owned property that's underutilized, that's just — you're holding it for future purpose.

We were also able to get a state grant from the Department of Commerce, our county human services, and of course, American Rescue Plan dollars. Pallet is so affordable. I think that as a city and you're trying to figure out your way out of this housing crisis or how to build a new shelter, you're talking millions of dollars, and it's overwhelming. It is so much more affordable that it's kind of mind blowing how much easier it is to get temporary shelter up. There are so many people that congregate shelter is not the appropriate solution for.

The folks that we were seeing in our city that were like, okay, we've got these great service providers, we've got these hotel vouchers, we've got these dollars in these programs, but none of our unsheltered population wanted to access those services. There were just too many barriers. And I needed a solution for the folks that were living in encampments, for the folks that really were service averse. We needed far less funding than we would have to buy a motel or build a shelter or acquire even a warehouse to house people.

The city continues to work on permanent supportive housing. That is our goal. We've built permanent supportive housing here. It takes years. We're very proud of it. We need so much more of it. We are continuing down that path, working with outstanding housing developers, our nonprofit partners that understand the population that needs services. But I can't wait four years for a new housing project to be built and for us to get all the complex funding for that. I needed something more quickly, and that's where Pallet came in to provide that bridge.

(Note: Federal funding from FEMA and HUD is also available to use towards building Pallet shelter villages, safe sleep sites, and other interim shelter solutions. Pallet’s Community Development team can connect cities and nonprofits with these sources.)

Pallet: What is the goal of these villages and what are the other measurable or quantifiable results that you consider successes?

Mayor Franklin: We had this area that was just a disaster. It was a huge encampment. We got so many complaints. It was not safe for the individuals out there. So we had angry residents complaining that we weren't taking care of the city. But I was also just really worried about the people that were living in those unhealthy conditions, health hazards. This is not an okay environment for people to sleep in.

We were able to get people inside living safely in their dignified four walls and the businesses that were impacted, again, this also helped us locate it. So all the NIMBYism like, ‘oh, this is going to make our neighborhood worse,’ actually it made the neighborhood better. It has improved the neighborhood. We took care of the health crisis. We have a safer neighborhood there now. And the people in the Pallet shelter community are after months, it takes time because these are service averse populations that have a lot of trauma from years of abuse on the streets and drugs and whatever illnesses they've been dealing with. But they are getting treatment, they are connected to social workers, they are getting medical treatment and some of them have been able to transition out of a Pallet [shelter] into permanent housing. So to me that's a huge win.

Pallet: How did you go about choosing the location you selected?

Mayor Franklin: It's the hardest thing right? No one wants to see people living outside. They get angry, but no one wants a shelter or any solution in their neighborhood, even affordable housing, which is just like housing. Honestly, people get worried about that. So the way we did it was I asked the team for a map of all of our public properties. I want every single public property. I want us to evaluate everything that we own, if any of those would be viable. I also asked to look at anything else if it was a site that they thought would be suitable. Probably not smack dab in the middle of a single family neighborhood. You're going to get the most NIMBYism and most pushback in that community. And so after the team, public works planning, our community development team and certainly working with Pallet, analyzed all of those different sites — how many people we would want to house and how we could get the services to the individuals — we identified one that was right behind our mission (Everett Gospel Mission). And again, that was hard because this was an area that was already being impacted by the services. We have the only shelter in the entire county right here in Everett.

And so they were like, ‘Are you kidding me? You're going to put more shelter in our neighborhood.’ The businesses and the residents in that neighborhood were scared, so that's why we looked at, okay, well, what can we do to improve the neighborhood? How can we make sure that this is actually going to be a positive impact, not a negative impact? And the no sit, no lie [ordinance] was very helpful.

We have two other Pallet shelter communities coming up. One is going to mainly house single adults, mainly single men. The next shelter is for women and children, and that is very close to a single family neighborhood. And so that is where that project will be going. And then a third site that we'll be discussing is on unused property that the city owns that is kind of somewhat close to residential, but more close to former industrial. So it's kind of like finding those transition properties in your city. That kind of where you're almost making everybody mad, your businesses and your residents, but it's not in the middle of anybody's area. Those borderline properties, and again, city owned.

Pallet: Anything else you’d like to add?

Mayor Franklin: I think separating the affordable housing crisis from the homelessness and kind of the street level issues that we're dealing with, they are not the same. The community gets them all mushed together, and that doesn't actually help us in our cause. So really talking about them strategically as separate issues that somehow they do relate, but they're separate issues. And so when you're talking about homelessness and the street level social issues and what we're dealing with there, finding solutions for non-congregate shelters are super important.

The main thing is land, education and balance. You've got to find the land and break through that, and that is achievable. Cities do have a lot of land. We did a ton of outreach before we put up the first Pallet shelter. Helping people understand this is not what you think it is. This is something very different. This is actually going to move people that are living outside causing problems for you inside and also educating the community. This is different than the other shelters you've experienced.

Breaking the cycle of homelessness in Aurora, CO

Pet ownership is a quintessential part of American life. Statistics show 70 percent of households across the country own at least one pet. From parks to specialty items, there's an entire industry catering to the needs of furry family members. But when a pet owner is unhoused, their ability to care for an animal is questioned.

A prevailing myth is that people without a stable place to live shouldn't own pets and should give them up. According to a Homeless Rights Advocacy Project (HRAP) policy brief, "this advice is predicated on the false belief that surrendering dogs to shelters is superior to having a dog live on the streets with its owner." But that's not true. The brief adds, "shelter conditions alone cause severe animal suffering and unnecessary death." Some also falsely believe people experiencing homelessness are unworthy of owning a pet and are incapable of caring for them. These misconceptions are dangerous and have led to the harassment of homeless people on the street.

Jennifer, Human Resources and Safety Specialist at Pallet, knows firsthand the value of having a pet while homeless. Jennifer's bond with her dog Bailey began when she was housed, but later they lived in a car, then an RV. Bailey helped fill the void in Jennifer's heart and alleviate the pain and suffering she was going through. Jennifer was dealing with personal setbacks and substance use disorder at the time.

"Even in some of my darkest moments, Bailey was the reason I didn't just give up and quit and die. Because then it was like, what's going to happen to Bailey?" she shared. "She was literally my reason for not giving up and helped me really get through a lot."

Jennifer took great care of Bailey and was attentive to her needs. Homeless pet owners often feed their animals before feeding themselves. For Jennifer, Bailey was a source of protection, companionship, and unconditional love.